A map to utopia

Studying the maps of Utopia, Cockaigne, Elysium, Anavatapta Lake, and Atlantis.

This is a guest post by M. E. Rothwell, author of Cosmographia, about the maps illustrating utopian worlds. I’ll be back next week!

“A map of the world that does not include Utopia is not even worth glancing at…”

– Oscar Wilde

Hi 👋🏻 I’m M. E. Rothwell.

I write Cosmographia, where I share tales of the faraway. I also have a bit of an obsession with old maps.

The other day, I was rooting around in an antique maps and prints shop in Edinburgh, as you do, and came across a chart entitled "Accurata Utopiae tabula" — An Accurate Map of Utopia (1720). This got me thinking.

Cartography, or mapmaking, was once an art form in itself. It required knowledge of complex mathematics, aesthetics, and geography, as well as the artistic skill necessary to engrave printing plates, in reverse, with beautiful, yet functional, imagery. As a result, the most skilled cartographers were in high demand, and their work was not cheap.

Whenever you discover an interesting map from the 16th, 17th, 18th, or 19th centuries, you know a great deal of time and expense must have been invested in its production. One would need good reason, therefore, to map something as whimsical as a fictional land.

But, more than that, people come to know the world through their maps. As cartography developed through history, we can–quite literally–map the changes in worldview over time (for example, in Near Eastern and European cartography, Jerusalem was marked as the centre of the world for centuries). These old charts, then, are windows back through time, glimpses at humanity’s hopes, fears, and ways of perceiving the world. “Here be monsters,” and vast stretches of “Terra Incognita” say more about the people who made the maps, than the land they’re supposed to represent.

So, after the discovery in the Edinburgh shop, I began reading all I could about maps of Utopia. It turns out there were many, and each had its own fascinating story.

Without further ado, then, let’s embark on a journey through the weird and wonderful Cartography of Utopia.

Thomas More’s Utopia

There is nowhere else to start other than with Thomas More. Elle has written about the great humanist philosopher, lawyer, and writer elsewhere in this newsletter, so I’ll try not to rehash old ground too much here.

In coining the word “Utopia” (directly translating as “no place”, but deliberately close to “eutopia”, meaning good place), More was setting out a debate for two contrasting approaches, one idealist and the other pragmatic, towards building a better society. He does this via conversations with a fictional traveller, Raphael Hythalodaeus, who he links with the real-life voyages of Amerigo Vespucci (after whom America is named).

More has Raphael as one of the 24 men who Vespucci leaves at Cabo Frio (modern day Brazil) in 1507. According to the story, Raphael travelled further on and found the island of Utopia, where he spent five years observing their customs.

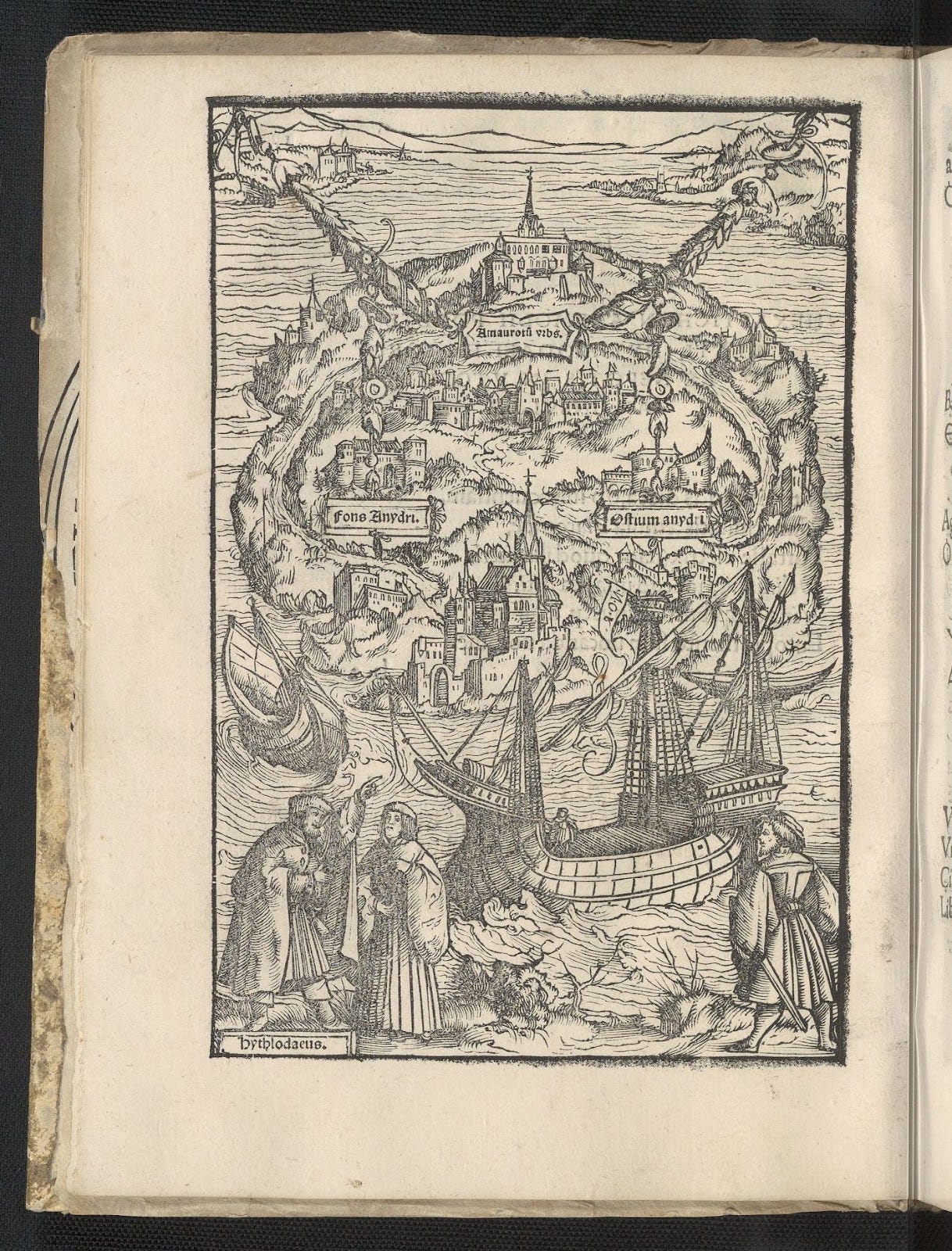

Ambrosius Holbein, author of the above print, was actually more of an artist than a cartographer. He draws the island of Utopia surrounded by water and dotted with a few towns. The labels mark out the island’s capital, Amaurotum ("Mist-town") and the source and mouth of the river Anydrus ("Waterless"), which flows in a semi-circle. At the bottom left, Holbein has sketched in Raphel telling More all about the mythical land.

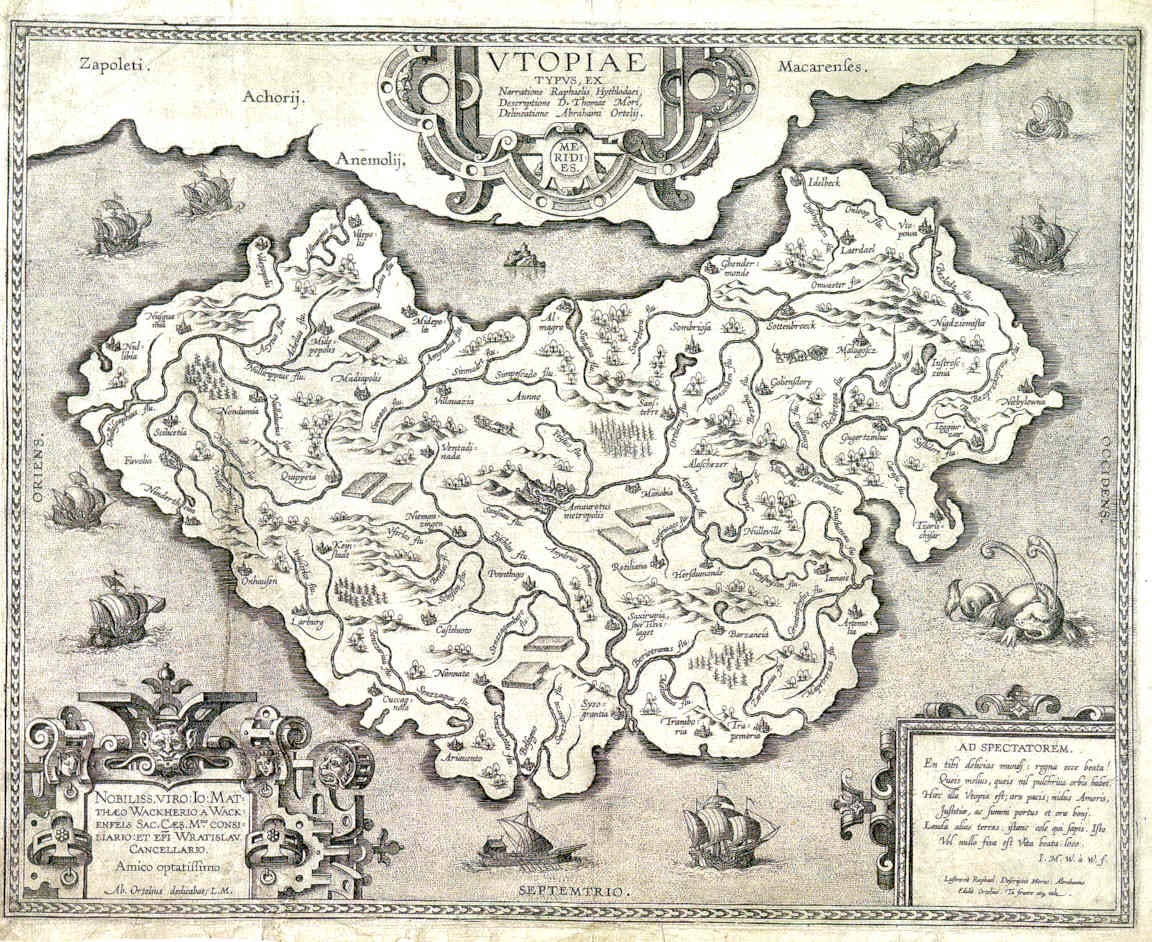

For a later edition of More’s book, the publishers managed to enlist the services of one of the most important cartographers of the day, Abraham Ortelius. Known for creating the first modern atlas of the world, here he’s drawn a much more convincing map of the island of Utopia. Though closer to Raphael’s description than Holbein, Ortelius adds in an extra city (taking the total to 55), which he calls “Favolia” after the Antwerp scientist Johannes Baptista Favolius, and he adds in three extra rivers which he names after himself and three friends, “Felsius”, “Ortileus” and “Mavonius”. One can’t but respect the audacity to name a location in utopia after yourself.

The Land of Cockaigne

The Land of Cockaigne is a land of extreme luxury and ease in medieval myth—a place where food, drink, and physical comfort abound. In Cockaigne, or Schlaraffenland in the German tradition, the sky would rain with cheese, crops harvested themselves, lakes were filled with wine, and nuns would show their bottoms. This all sounds rather weird to us, but given the context of the extremely bleak lives of medieval peasantry, one can see why the poor souls would have taken to daydreaming of a fantasy land of plenty.

Johann Baptist Homann, however, has less sympathy. His map of Cockaigne is meant to mock the idea of an earthly paradise and all the sins that people wish to indulge within it. Note the drunkards slumped over the cartouche at the bottom right, enclosing a description that includes, “This is the newly invented, humourous chart of the World of Fools.”

There is much fun to be had in decoding the names of the kingdoms spread across the map, such as Pigritaria (Land of Indolence), Lurconia (Land of Gluttony), Bibonia (Land of Drink), and Schmarotz Insula (Island of Spongers). To the north lies Terra Sancta (Heaven), which is of course incognita to us mere mortals, while the more accessible Tartari Regnum das Hollische Reich (Empire of Hell) lies at the very south.

The moral of the joke is clear: reform your sinful ways.

The Fortunate Isles // Elysium

The Fortunate Isles were a group of semi-legendary islands that were sometimes treated as a real geographical location, sometimes as a part of the Underworld, and sometimes both simultaneously.

In Greek mythology, these islands were part of Elysium—an afterlife realm reserved for the heroes of myth like Achilles, Ajax, and Harmonia. In various legends, the Isles of Blessed, as they were sometimes known, were said to lie out west of the Mediterranean, somewhere off the coast of Africa. These legends informed ancient cartography, with the great geographers like Marinus of Tyre, Claudius Ptolemy, and Strabo, drawing them on their maps.

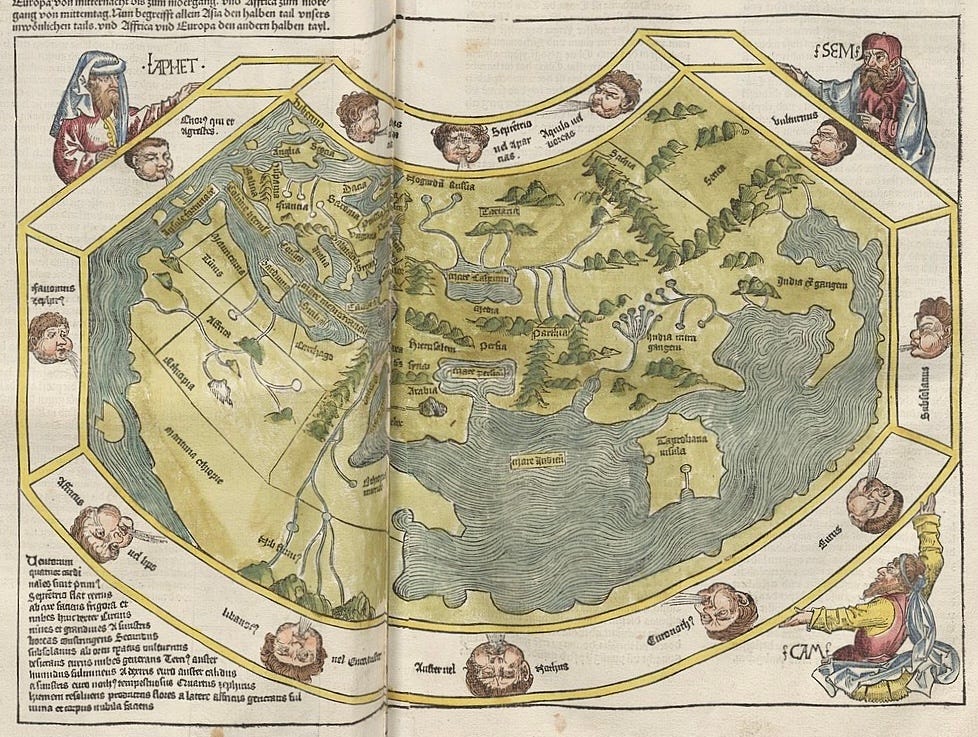

Despite coming a year after Columbus discovered the Bahamas, Michael Wolgemut’s map uses the 14 centuries-long tradition of mapping the world according to Ptolemy’s Geographia.

Claudius Ptolemy (c. 100–170 AD) was an intellectual titan, even among the many polymaths of the ancient world. He wrote no less than a dozen treatises, of which three—Almagest, Geographia, and Tetrábiblos—became the foundation-stone of Byzantine, Islamic, and Western European science and geography. His work was so significant it has never ceased to be copied or commented upon since it was first published, almost two thousand years ago. He was so far ahead of his time, that few of the later scholars using his work could understand its mathematics, and had to water it down.

Several clues tell us this is a Ptolemaic world map: notice the legendary Mountains of the Moon feeding the Nile; the oversized island of Ceylon (Sri Lanka); and, lying off the westernmost edge of North Africa—the Fortunate Isles. Ptolemy used the islands as his prime meridian–the point at which longitude is 0°. It’s possible that Ptolemy may have known of the Canary Islands (Greek and Roman sailors may have visited), and these were what he called the Fortunate Isles, but we can’t know for sure.

I, for one, prefer the idea that Ptolemy believed a ship could sail straight for Elysium.

Anavatapta Lake

According to an ancient Buddhist cosmological tradition, Anavatapta (“the Unheated”) is a lake that lies at the centre of the world. This magical body of water, often associated with the real Lake Manasarovar in India, is believed to mark the very centre of the universe where Queen Maya conceived the Buddha. Its waters are thought to soothe the fires that torment conscious beings and to contain a dragon who had achieved bodhisattva. From Anavatapta’s quadruple helix comes all water on Earth, flowing from four sacred rivers: the Indus, the Ganges, the Bramaputra, and the Sutlej.

As the first Japanese map of the entire world, including Europe and America, this is a seminal piece of cartography. Printed by woodblock, its author, Rokashi Hotan—a Buddhist monk—has blended early modern cartography and Buddhist cosmography to give us a rather unusual looking world map.

At its centre we can see the many-headed whirlpool of Lake Anavatapta. As your eyes wander southwards, India's familiar peninsula emerges. Japan, too, is identifiable, depicted as a string of islands in the East. Everything else is harder to ascertain.

China and Korea, found to Japan's west, are just about identifiable, and Southeast Asia is shown as a cluster of islands beside India. The islands on the far western side are some of the first-ever depictions of Europe on a Japanese map—countries like Hungary, Holland, Albania, Italy, France, and even England are labelled. Meanwhile, Africa is represented as a diminutive island, dubbed the “Land of Western Women.”

Hotan's rendition of the Americas is particularly noteworthy. Before this, America seldom featured on Japanese maps. South America appears as the tiny island in the southwest and he’s drawn a land bridge, possibly the Aleutian Islands, between Asia and North America.

Atlantis

The (very fictional) island of Atlantis first comes to us via Plato:

“[F]or in front of the mouth which you Greeks call, as you say, 'the Pillars of Heracles [Straits of Gibraltar],' there lay an island which was larger than Libya [Africa] and Asia together… Atlantis.”

– Timaeus, Plato (c.360 BC)

The Greek philosopher uses the (very fictional) story of the fall of the Atlantis civilisation as an allegory warning of the danger of national hubris. Though not initially imagined as a utopia (indeed, quite the opposite), in the centuries since Plato first told his story of Atlantis the imaginations of writers, philosophers, cartographers, and dreamers have been ignited by the long-lost island, somewhere out there in the Atlantic, and reimagined it as an ideal society.

Sir Francis Bacon, for example, titled his utopian novel New Atlantis.

At first glance this may just appear to be an ordinary early map of the Americas: California appears as an island, the northwest of North America is poorly defined, and the Great Lakes are greatly misshapen. But look again at the cartouche on the bottom right—“Atlantis Insula.” Peer carefully at the labels adorning the two continents and you’ll find the names of Poseidon’s ten sons, whom Plato said were the rulers of the forgotten continent: Atlas, Gadeirus, Ampheres, Evaemon, Mneseus, Autochthon, Elasippus, Mestor, Azaes, and Diaprepes.

With the discovery of the New World at the end of the 15th century, it didn’t take long for thinkers like Francisco Lopez de Gomara, Francis Bacon, and Alexander von Humboldt to equate this new land with that of the Atlantis of old. Nicolas Sanson, Royal Geographer of France, states this plainly with his map.

Though it’s safe to say the next five centuries of American history after its discovery were far from a perfect utopia, perhaps Sanson’s vision should give us pause. We once thought of this bountiful continent as an opportunity to create a better society for all. We should dare to dream again. How do we go about getting there?

Well, that I’ll leave to Elle Griffin and The Elysian, but just know this: having a map helps.

Thank you Elle for hosting me on The Elysian!

See you all in Atlantis someday soon

I love your love of maps. Whenever someone has something that they are specifically passion about it, I find myself excited about it, too, even if it's a thing that I'm not personally interested in. Anytime something about maps comes up here on Substack, I think of you.