A self-governing forest

Terra0 thinks nature should become economically independent.

This essay is for TERRAFORM, an essay collection about the future of our planet. Support the project by collecting the digital or print edition 👇🏻

Imagine walking through a forest that has the same rights to exist as you and me.

Imagine the forest cannot be sold or harmed or killed the same way that humans cannot be sold or harmed or killed. (That is to say, not without consequences.)

Now imagine it self-governs. It owns the land it dwells on, can earn its own money by deciding what percentage of it to cut down and sell, and can use those profits to buy up more land and expand without human intervention.

This is the dream of Terra0.

The artist collective consists of two men named Paul and began with their 2016 whitepaper, “Can an Augmented Forest Own and Utilize Itself?” The paper ventured the idea that forests could attain personhood, use sensors and satellite data to trigger actions and generate logging contracts, and self-replicate without human exploitation.

“Whenever we propose this project, one of the first questions is always: ‘If a forest owns itself, what would it do if someone just goes there and cuts a tree?’” Paul Seidler said in an interview. “Nobody would ask this question if a person owns a forest because it would fall within a jurisdiction that provides ways to address such legal infractions.”

If land were protected as people and their property are, this would be a non-issue. Some places already are. The Whanganui River in New Zealand, for one, was granted legal personhood in 2017. The river had been used for fishing and transportation by the Whanganui iwi people until settlers confiscated property and polluted its waters. After 140 years of legal battle, the courts ruled in favor of the tribe. Two guardians, one chosen by the government and one by the Whanganui iwi, now act on the river’s behalf.

In 2008, Ecuador became the first country to add a “Rights of Nature” article to their constitution, granting citizens the right to sue on behalf of nature, and they have! In 2011, residents successfully sued a provincial government for road construction that dumped debris into the river—the court ruled in favor of the river, ordering restoration. In 2021, the courts blocked a mining project in the Los Cedros Cloud Forest, one of the most biodiverse areas in the country, citing the rights of the forest and its species.

Terra0 takes this a step further, experimenting with the idea that land should not just be protected, but economically independent. Their 2021 project “Two Degrees” experimented with this concept. At a Sotheby’s auction, Terra0 sold NFTs depicting lidar scans of a forest in Germany. They were investments, as auctioned art often is, but with a catch: If the Earth’s temperature reaches 2℃ above pre-industrial levels, the artwork will automatically disappear and the art’s worth will go to zero.

This incentivizes investors to ensure the environment is treated well as a way of protecting their investment. Like an art collector storing their Monet in a temperature-controlled vault, here the value comes not from preserving the painting, but the planet.

“Two Degrees addresses the relationship between global warming and the critical survival of the imaged (eco)systems in an obvious manner,” the Pauls said in a post at the time. “Just as the real forest will disappear as soon as a certain threshold in global climate change is passed, so will the NFT.”

Artists have long been able to condition the sale of their art the same way founders can condition the sale of their companies, giving the owners control over their future economic value. It is a condition of Margaret Atwood’s book Scribbler Moon that it not be released until the year 2114, once a Norwegian Forest planted in 2004 has finished growing the pages for it. It is a condition of Yvon Chouinard’s company Patagonia that it be held by a trust ensuring the company acts in the best interests of the environment.

In this way, both art and commerce can set the economic conditions that will give it value. Sometimes artistic value can even be more effective than corporate value. As collectors in 1964 famously quipped: “General Motors has done a little better than Cézanne, but not as well as Renoir.”

And what if a Renoir was only as valuable as the garden it was painted in? As with Margaret Atwood’s book or Yvon Chouinard’s company, what if investors only benefit because our environment does?

Terra0’s 2024 project “Conditional Power” expanded upon this idea, selling nine NFTs each deriving value from a different environmental concern. So far, four of them have been revealed: A forest that Tesla might clear for its gigafactory, and various patches of ice that will disappear when the ice does. Every NFT will self-destruct when the land it represents does, and the investment will be worth nothing.

“It serves as a conceptual framework illustrating how artists can leverage their agency to gain political influence by creating assets and speculative objects,” the artists wrote. “While metaphorical in a specific context, it also proposes mechanisms to incentivize owners to act conscientiously in the face of future challenges.”

There are many ways in which this might not work. As an investor, why would I invest in a forest that Tesla will certainly clear? Unless there is something I can do about it, my investment will surely be worth nothing. Not to mention, Terra0 relies heavily on the blockchain and NFTs where there is little secondary market. It is unlikely I will be able to sell any of the NFTs I purchase, much less see them increase in value.

Similar concerns plague artists off chain. The artist Banksy, for one, attempted to destroy the value of his work “Girl with Balloon" soon after it sold for $1.4 million, but in trying to make an investor’s millions worth nothing, a bold statement about wealth, he made the work more valuable. Companies are similarly affected. An unintended side effect of Elon Musk’s US political involvement was that his electric car company Tesla became less valuable, an important environmental concern devalued by a volatile political actor.

But we should never underestimate the power of prestige, in both art and commerce. Salvador Mundi, a highly disputed da Vinci painting, was sold for a record breaking $450 million, not because it was a good investment, but because it flaunted a certain wealth and religious affluence. The Washington Post and Twitter were bought by Jeff Bezos and Elon Musk, not because they were profitable businesses or good investments, but to gain media clout and influence.

One of Terra0’s NFTs was purchased by Mercedes-Benz' blockchain arm, presumably in line with the electrification of their car fleet.

Most importantly: There is inherent value in art which can experiment in ways commerce can’t, and I often invest to support this idea alone. Artists exist in a theoretical or hypothetical plane, without the pressures of real world implementation. They play in a microcosm, a “little world” that can be scaled up to the larger one as available. Science-fiction authors have dreamed up futures long before technologists built them, and for all of the ways the blockchain hasn’t lived up to its potential, it has proved an important sandbox for experimenting with ideas like autonomous organization, fractional investment in art, and IP ownership.

Only a couple years ago, I crowdfunded a short story using Ethereum with readers able to purchase the chapters as NFTs. I earned about $5,000 in Ethereum value at the time, and the book was owned, not just by me, but collectively by readers. I loved the experiment as a hypothetical, but it was a niche art project that wasn’t about to disrupt publishing. This year, I took that idea off chain and crowdfunded ownership in a nonfiction book. I’ve so far raised $60,000, and once again readers own a share of my work and benefit from it as stakeholders. My hope is that what begins as fractional ownership of art, could more broadly become fractional ownership of commerce.

What other ideas might currently exist in the exploratory world of art, but later become mainstream?

Perhaps the idea that it is economically beneficial for the natural world to exist.

After all, we need trees. We need them to clean our air and produce more rain and create more habitable places to live. Filling the world with as many trees as we can is beneficial for humanity. Unfortunately, trees hold little value economically, and so they are cut down for more profitable endeavors like growing beef or corn or wood products. If we want to create a world where forests exist, we need to create a world where it becomes economically beneficial to have trees, and who better than the artists to come up with something like that?

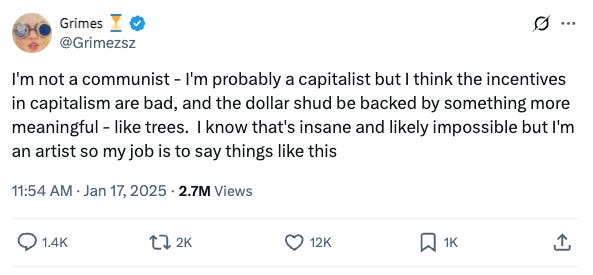

In a recent tweet, the musician Grimes wondered if we could even back money with trees. “I'm probably a capitalist,” she said, “but I think the incentives in capitalism are bad, and the dollar shud (sic) be backed by something more meaningful - like trees. I know that's insane and likely impossible but I'm an artist so my job is to say things like this.”

It is an artist’s job to have impossible ideas. And Terra0 retweeted the sentiment because they are experimenting with creating it.

After all, tying economic value to environmental value is effective. Carbon taxes, for one, put a price on each ton of CO₂ emitted, making it more profitable for companies to emit less carbon. In the fishing world, “cap and trade” quotas work almost like stocks, divvying up the available fish population into shares fisherman can buy and sell—the more fish you take, the more expensive it is. When New York City was faced with an $8-$10 billion bill to build a water treatment plant, they realized it was more cost-effective to protect the forests and streams from becoming tainted instead. For only $1–$1.5 billion they bought up land, restricted development, supported farmers with pollution control, and protected a clean water source for their citizens.

Then there’s mitigation banking—holding companies accountable for the land they destroy by forcing them to replenish it. If Tesla needs to destroy a forest to build a gigafactory, why shouldn’t it be responsible for funding the growth of another one just like it?

In all of these cases, there is an economic incentive to treat the environment well, and Terra0 would like to see that expanded.

Their newest project, “Autonomous Forest,” returns to the thesis of their 2016 whitepaper, and adapts it for real world implementation. They describe it as “a work of land art that leverages the collective power of people to enable the autonomy of forests.”

Here they depart from the “self-governance” their original white paper imagined. If it was once data inputs that informed the actions of a forest, the Pauls have learned that real world implementation requires people. “We need to address how to build a group of people who maintain interest, invest financially and emotionally, and contribute their time and capacities if we actually buy a forest and implement this long-term project,” Paul Kolling said in an interview.

Or as Seidler put it: “Collective ownership is the closest to non-ownership in protecting something from external influences.”

Many forest projects around the world have discovered the value of collective ownership. After various programs to plant large monocrop forests failed, newer iterations got local communities involved. Africa’s Great Green Wall project, for one, didn’t just plant trees and leave them to die, but supported 17,000 small farmers with grants, training, seeds and tools, as well as ongoing stipends to help the small plot in their charge thrive and grow.

Details for “Autonomous Forest” have yet to be released, but the project currently links to a Telegram channel that posts time- and temperature-stamped photos of animals spotted in a German forest, including deer, wild boar, and foxes. Three cameras established in mid-2024 trigger movement alerts, and give every indication that the smart forest they proposed more than 10 years ago might finally be a reality:

A forest that can be monitored remotely, whose health and vitality can be tracked in real time; and with collective ownership, one we might be financially incentivized to protect.

Maybe not a self-governing forest, but a collectively governed one, with the same rights to exist as you and me, and with an economic incentive to thrive.

But I’d love to know your thoughts.

Thanks for reading and thinking with me,

Founder, The Elysian

P.S. If you liked this essay, please share it. That’s how I find new readers and earn a living for my work!

"It is an artist’s job to have impossible ideas." Yes! A self-governing forest, or a self-governing park adjacent to Wall Street. The artists set the agenda for the Occupy movement, Nathan Schneider argues in Thank You, Anarchy (pages 145-47), and they saved the movement from a debilitating schism between its nonviolent contingency and its "diversity of tactics" contingency by exciting the creative sides of both sides, enticing both sides to work together again.

The self-governing forest aided by human beings reminds me of the indigenous concept of a forest and its occupants as people. Saving the earth while merely reigning in global capitalism, I think, would take everything the likes of artists, anarchists, and indigenous wisdom could summon on the earth's behalf, and then some.

What an incredible concept. I love this idea of fragmented ownership of public resources. I also agree that NFTs are going to have to offer some other kind of inherent value beyond simply status in order for them to become viable investment options.