An alternative to "tax the rich"

It’s not wealth that’s the problem, it’s the distribution of it.

If my last essays made the case that profits could be used for good, my question then becomes how do we incentivize companies to do that?

After all, “getting rich” is a pretty good incentive. And would companies (shareholders) be just as incentivized to make their company rich if that money also went to their employees and their communities?

Some would. Some executives have already realized that they don’t need millions of dollars and that they would rather use some of that extra cash for good. Like those at Dr. Bronner’s.

“We're not going to get into this ridiculous trap that so many people fall into: The bigger house, the bigger car, whatever private school, executive bonuses,” David Bronner, CEO of Dr. Bronner tells me. Instead, the company implemented a guideline that top salaries at the company cannot exceed five times that of the lowest-paid worker with five years on the job. As a result, executives at the company pull in a $300,000 annual salary.

This has meant the company is free to use their profits 1) for the benefit of their employees who, as a rule, receive more than adequate pay plus an annual $7,500 childcare stipend and annual bonuses up to 10% of their pay; and 2) for the benefit of the communities they serve. The company donates about 40% of its profits to charity each year and that’s what motivates them to keep the whole thing cash positive. And away from investors.

The company is poised to generate $200 million in revenue this year and David estimates that, as of this year, the company will have donated more than $100 million over the last 20 years.

Why won’t other companies do that? Should we make them? (Use their profits to pay their employees well and support their communities?) Because right now, most companies give the bulk of their wealth and earnings, not to their employees or communities, but to the executives at the top. And in amounts far greater than $300,000 a year.

According to the Economic Policy Institute, between 1978 and 2021 CEO compensation grew by 1,460% and top 0.1% compensation grew by 385%, while typical worker compensation grew by only 18.1%. In 1989, CEOs made $59 for every $1 earned by a typical worker. By 2021, CEOS were making $399 for every $1 earned by a typical worker.

GDP has been on the rise this whole time, by the way.

So has productivity.

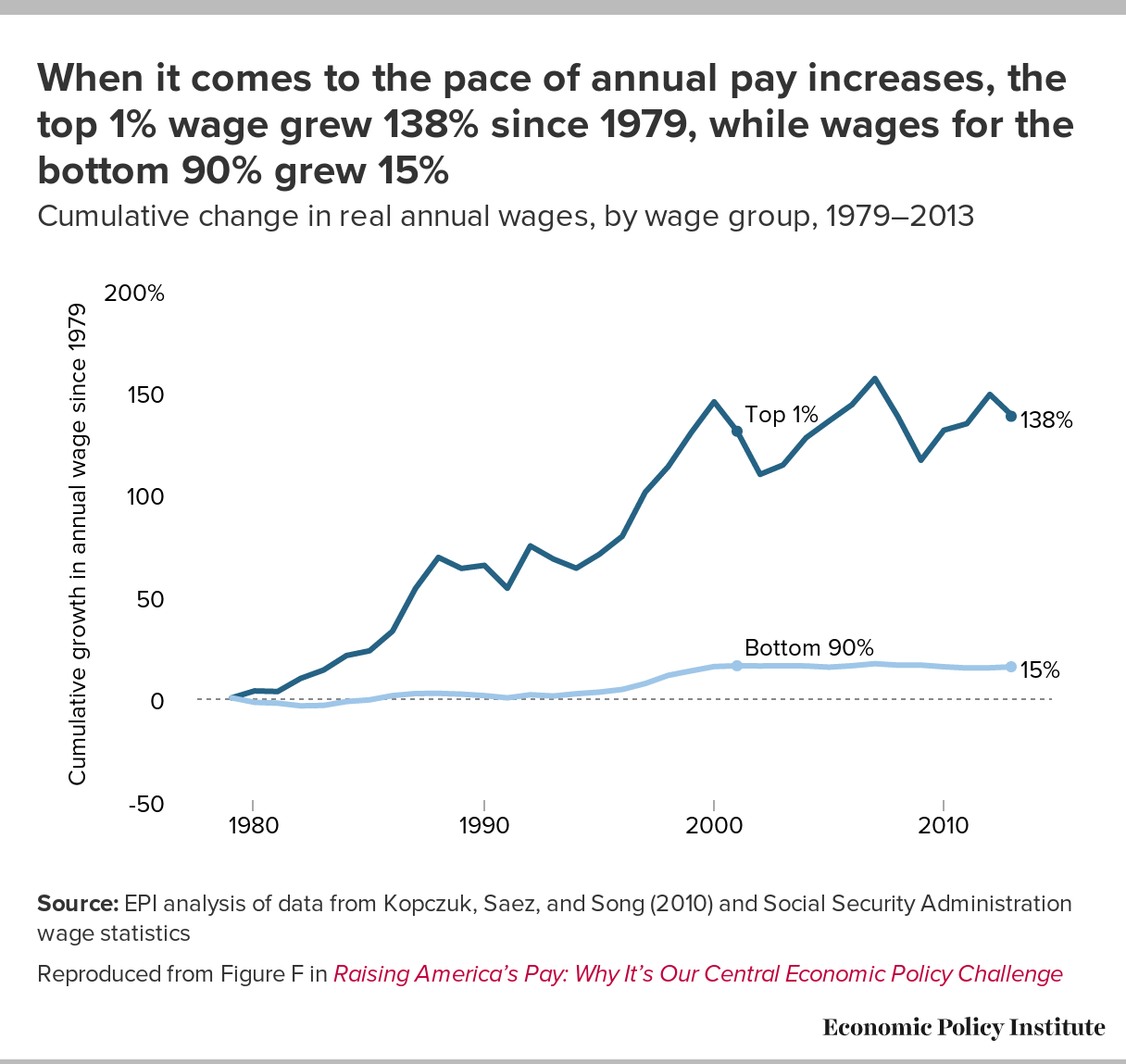

If we’ve been producing more and getting richer, how come growth in income only happened at the very top?

As we can see from the above charts, there is a major divergence that took place around the year 1980. What happened in the 80s and 90s that made executive pay skyrocket and typical worker pay plateau? For one, Ronald Reagan passed his Economic Recovery Tax Act in 1981, reducing taxes on the wealthiest income bracket from 70% to 50%. By the time he left office in 1989, he had reduced that to only 28%.

At the same time, the minimum wage remained flat, but inflation meant that it was worth less. Look at what happens between 1980 and 1990 👇🏻

Already concerned with the sudden rise of CEO pay, in 1992 Bill Clinton campaigned with a solution: If a company wanted to pay a CEO more than $1 million a year, the company shouldn’t be allowed to deduct any more than that from their earnings. This meant that if a company wanted to pay a CEO $2 million, it would have to justify to its shareholders why this person was worth taking more money out of their pockets.

Berekely professor Robert Reich was working as the secretary of labor at the time and he was all for it. But, as he explains in his recent lecture, his peers disagreed. Companies needed to compensate CEOs well if they wanted to attract them, they said, so they came up with a “compromise:” Companies couldn’t deduct more than $1 million in annual salary, BUT they could deduct more than that in stock options. Clinton agreed to the compromise and it became IRS legislation in 1993. As a result of this huge loophole, companies quickly started paying their CEOs in stock instead of salary.

As the Economic Policy Institute points out: “They are not getting higher pay because they are becoming more productive or more skilled than other workers, or because of a shortage of excellent CEO candidates,” Rather, “CEOs are getting ever-higher pay over time because of their power to set pay and because so much of their pay (more than 80%) is stock-related.”

As the overall economy grew, so did CEO compensation. When we compare the rise of CEO compensation with the growth of the stock market, suddenly the picture becomes a lot clearer.

CEOs got really rich because the stock market got really rich and that’s how they were getting paid. And the rest of the company, who earned a static salary, kept their same salaries and stayed flat. The result has been a wide, but totally fixable inequality.

Not that I think politicians are necessarily coming up with a fix. Calls to “tax the rich” are all interesting ideas, and they might be worth considering now that we’ve created a huge inequality problem and have to figure out how to fix it in retrospect. But those ideas aim to get more money from companies and individuals who are already rich and that feels a lot like treating the symptoms rather than the cause.

Why do we let people get insanely wealthy to the point that the government needs to exorbitantly tax them to make money? The problem, we must remember, is not that the executives make too much, but that the rest of the company earns too little by comparison. People become billionaires because they are earning a greater share of everything upfront, not because they aren’t being taxed enough at the end.

To me, this means that we need a better distribution of wealth when it’s being made. And couldn’t we fix that with a better compensation equation? Couldn’t we put something like Dr. Bronner’s equation in place? “Top salaries at the company cannot exceed five times that of the lowest-paid worker with five years on the job” is a pretty good start. And maybe that should apply to stock options too. “Top equity shares at the company cannot exceed five times that of the equity shares of the lowest-paid worker with five years on the job,” could go a long way.

“I’d love to see that. There should be more companies set up like we are,” Bronner agrees, though he admits a less aggressive number might be more replicable. Instead of a five-to-one compensation structure and a mandate of donating 40% of its before-tax profits, he thinks companies could commit to a 10-to-one compensation structure and a commitment to donate 10% of profits to charity. He even plans to prove it.

“We're actually contemplating creating a new business association. It's very conceptual at this point, but it's something that has a real cap and a real commitment. We've been thinking a 10-to-one cap on salaries and a minimum of 10% of before-tax profits given each year. There'd be other criteria to be part of it—everyone gets a living wage, everyone has credible eco-social certifications to confirm that environmental social impacts are good, and if you don’t comply you’d be kicked out—but the hope is that we can identify other businesses that are succeeding like we are and come together to formalize our model. To raise a flag for founders and entrepreneurs, investors, and philanthropists and prop up similar kinds of social ventures.”

If more companies can prove that this model is successful, then maybe the government can step in and regulate it, applying those standards to all companies. After all, the Fair Labor Act didn’t start with government regulation, it started with working case studies. Ford and Kellogg implemented a 40-hour workweek and started paying their employees better before everyone else did, and once we knew that it worked, the government stepped in to make that the law, establishing a minimum wage and a 40-hour workweek. And maybe we can do that again, introducing new regulation that ties the incomes of the top to the incomes at the bottom, while mandating that a percentage of profits be used for the greater good.

I don’t think there needs to be a pay “cap” so much as there needs to be a better formula to make sure the top isn’t quite so far from the bottom at the onset. Keep the drivers of capitalism in place, I say, but cut the employees and community in on the deal. If money is a good motivator then wouldn’t it be better to motivate the entire company to make it successful rather than just the few at the top?

Because we wouldn’t need to “tax the rich” if the money was better distributed when it was made. And maybe then we would start moving toward a better wage equality.

But I’d love to know what you think. Join us in the literary salon for further discussion 👇🏻

Thank you for thinking this through with me,

Marginalia

Here are a few of the things I read while researching this essay, and all my thoughts that might be found in the margins.