Ancient Olympians wouldn’t qualify for today’s Games

Science and technology have reengineered the human body beyond its limits.

A version of this article originally published on Freethink. This is “Elle’s Version.”

This May, former Olympian Kristian Gkolomeev swam the 50-meter freestyle in 20.89 seconds—faster than any other person on Earth.

The record didn’t count.

As part of the Enhanced Games, Gkolomeev took performance-enhancing drugs to achieve it. The organization launched last year to take full advantage of human ingenuity—to see what the human body is capable of achieving if aided by every scientific and technological breakthrough we have to offer.

We may not recognize his record internationally, but we can’t deny that technology has pushed the human body far beyond what Greece’s ancient athletes could have achieved. Every person on a podium today got there, not just because they are athletically superior, but because they have been scientifically and technologically optimized to be superior.

This, we should recognize, is a new form of progress.

The body as moral progress

During the Hellenistic period, military strength secured nations and conquered territories, and battle was fought physically on the field. What we knew about the human body was what we could see, and a visceral presentation of strength required physically adept warriors. Warrior kings like Alexander the Great were depicted as ideal physical specimens. Plutarch described him as “of a strong and active body.” Ancient biographer Arrian proclaimed that “Alexander was strong in body, a lover of toil, very brave, and with a mind as enduring as his body.” Biographer Curtius Rufus, meanwhile, said, “He was conspicuous in his appearance; his body, though not tall, was so well-formed that it won admiration.”

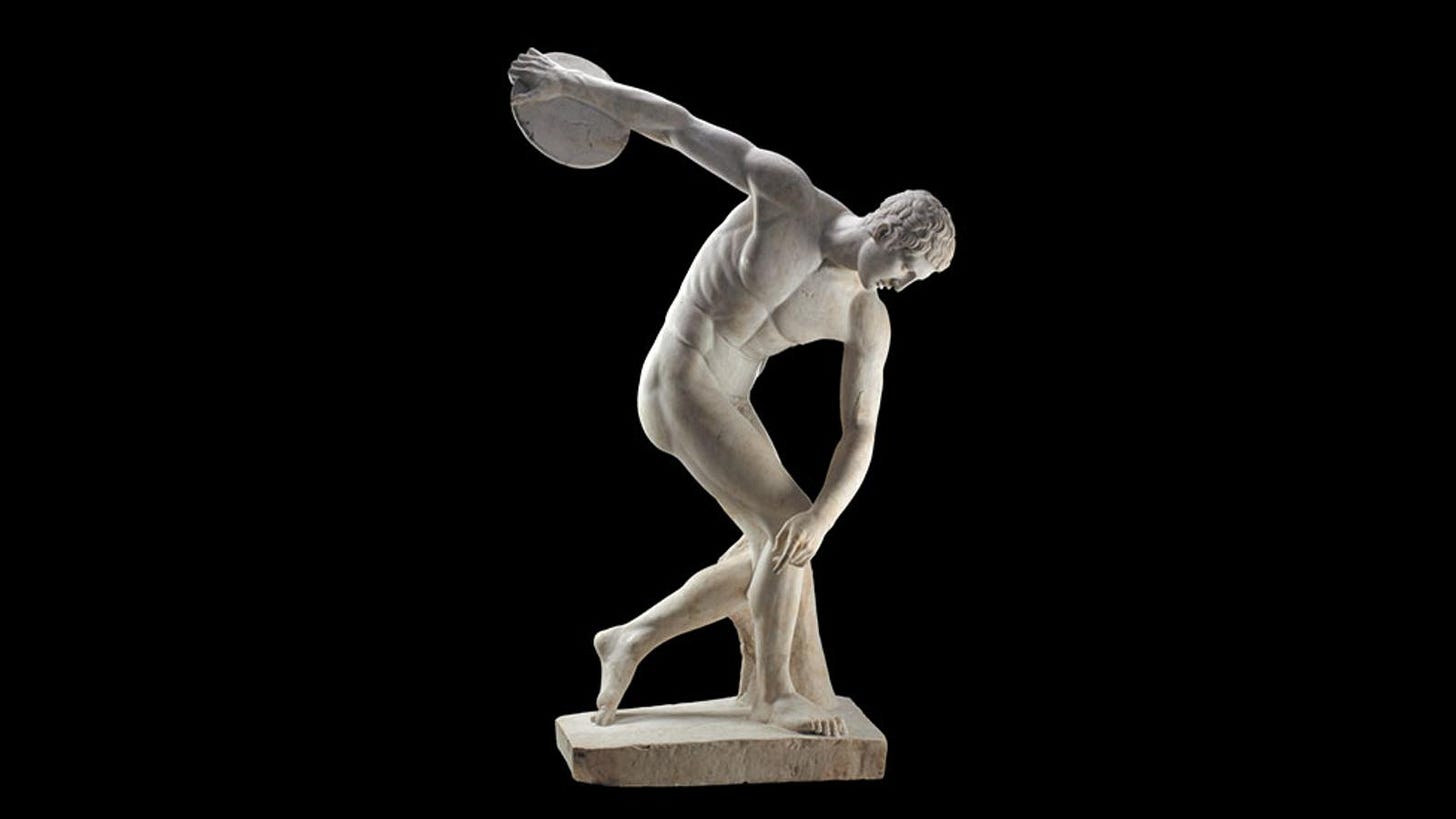

To the ancient world, strength of body implied strength of moral character. The Greeks developed the concept of gymnasia to this end, honing the physical body for battle and honor and holding Olympic contests to prove greatness and strength. Olympic athletes won a crown of wild olive leaves cut from a sacred tree near the temple of Zeus, but the real reward was honor and glory. Poets like Pindar composed odes for victors, and statues of winners were erected at Olympia or in the athlete’s hometown. The Spartans’ rigorous agoge system was a state-run program to mold physically perfect and morally disciplined citizens. Boys were encouraged to develop “scarless” bodies, and a warrior’s physique was presented as a visible measure of his moral discipline, courage, and loyalty to the polis.

The inverse was also true. Weakness in body implied weakness of moral character and the Greeks ostracized the infirm while Spartan children who could not live up to their training were shamed or cast aside. One Athenian statesman, Alcibiades, indulged so much in luxury that he was seen as soft, lacking discipline and moral fiber. Another, Demosthenes, was mocked for his frail constitution and weak voice. To counter this, he famously trained his body and speech, running up hills reciting verses, and speaking with pebbles in his mouth.

The body as scientific progress

In the ancient world, anatomical knowledge was largely based on the works of Galen, a 2nd-century Greek physician whose texts were based on animal dissections and thus often inaccurate. But Renaissance dissections, performed on humans by anatomists like Andreas Vesalius, allowed us to finally make accurate maps identifying the various organs in the human body.

As dissections started to become more popular, people gathered in public to peer inside the human body. Leonardo da Vinci participated in more than 30 dissections, commenting that “the human foot is a masterpiece of engineering and a work of art.” When William Harvey proved in 1628 that blood circulation worked like a pump-and-pipe system, Descartes, in his “Treatise on Man,” said, “I suppose the body to be nothing else but a statue or machine … composed of bones, nerves, muscles, veins, blood and skin.”

The human body became a natural specimen, something to be studied and documented alongside plants and animals. When Charles Darwin published his theory of evolution in 1859, it was a massive shift for humanity. The human body was no longer a product of the gods, but survival of the fittest—our bodies engineered by millions of years of natural selection.

This came with a dark side. Inspired by Darwin’s theory, the eugenics movement sought to engineer evolution and “perfect” the human race. After a 1,500-year absence, the Olympics were revived in 1896, and it wasn’t long before the Games were used as propaganda. The 1936 Olympic Games were held in Nazi Germany and intended as a demonstration of Aryan supremacy on the world stage. It didn’t work—African American sprinter Jesse Owens stole the spotlight, winning four gold medals and undermining racial ideology on the world stage.

As our understanding of the body progressed, so too did our health and well-being. We developed anesthesia and antisepsis, antibiotics and vaccines. We discovered germ theory and invented the X-ray. We cured polio and created synthetic insulin. During WWI, more soldiers died from infections than battle wounds, but by WWII, penicillin slashed infection deaths to near zero. Prior to the 1900s, global life expectancy was less than 40 years, but advances in the 1900s saw it skyrocket to the 60s, 70s, and 80s. If the ancient warrior’s chiseled body was a reflection of their personal morality, the body of a 20th-century senior citizen was a symbol of scientific progress.

The body as technological progress

In the 1950s, we reached a new shift. The first successful kidney transplant happened in 1954, with the pacemaker coming in 1958. Bionic limbs were next. Prosthetics became so advanced that, in 2012, sprinter Oscar Pistorius competed in the Summer Olympics despite having both of his legs amputated below the knee as a child. His carbon-fiber prosthetic legs were not just a one-to-one replacement for natural limbs, but seen by some as giving him an unfair advantage over other competitors.

Countless technologies allowed athletes to make incremental improvements to their performance. In 2008, Speedo introduced the LZR Racer, a high-tech polyurethane and neoprene swimsuit that compressed the body, reduced drag, and trapped air for added buoyancy. These “supersuits” gave swimmers such a large performance boost that, at the 2008 Beijing Olympics, 25 new world records were set. The next year, at the World Aquatics Championships in Rome, swimmers smashed 43 world records in one meet.

The suit was banned in 2010, but amazingly, most of those records have since been broken without the suit. Humans are getting stronger and faster, not from any evolutionary advantage but because technology has advanced far beyond the suit. Since 2010, pools have become deeper to reduce turbulence, and water circulation was redesigned to reduce drag. Goggles, caps, and textile suits are now engineered for hydrodynamics. Underwater cameras and real-time data on stroke efficiency have changed the game for training, and athletes now have access to near-perfect oxygen adaptation, nutrition, and recovery protocols never before seen.

The Enhanced Games takes that a step further, encouraging performance-enhancing drugs in the name of advancing human achievement. Gkolomeev was evidence of that—he was wearing a supersuit when he swam the 50-meter freestyle in 20.89 seconds. Shortly after, he broke the non-supersuit record, too. The organization plans to host its first major competition in Las Vegas in May 2026, with swimming, track and field, and weightlifting events. We may see several more world records smashed then.

Technology isn’t just making us faster, but also healthier. Wearables like Oura Rings and Garmin watches continuously track our heart rates, oxygen saturation, and movement, and the Apple Watch now has FDA clearance to flag irregular heart rhythms and alert users to potential strokes. Researchers are using cutting-edge tech to 3D-print organs and regrow tissue and cartilage, while AI is advancing drug discovery and disease diagnostics, making it one of our most powerful weapons in the battle against today’s top causes of death, including cancer and heart disease.

If the Greek warrior’s body once symbolized moral discipline, and the 19th-century patient’s body reflected the triumph of medical science, future advancements in longevity and healthspan will show what can happen when the human body meets technological progress. From ancient arenas to modern laboratories, each step forward reveals that there’s seemingly no limit on how far we can push our physical potential.