Bring back the "Renaissance Man"

In pursuit of everything.

The night was getting late, we were gathered in the salon of an Airbnb in San Francisco, Maarten Boudry was playing the piano and Jason Crawford was crooning a tune as a lingering cast of intellectuals drank wine and tried our best to sing along.

Jason was our host, the rest of us participants in his Roots of Progress Fellowship. We’d spent the weekend together, talking about our ideas for the future, and pondering everything possible for this world and ourselves.

Amidst that group, I’d struggled with where I fit in the progress movement. The rest of the fellows were so academic in scope. I wondered if I was the only person in the room without a PhD, or at least planning to get one. I am not a scientist or mathematician, I’m not going to invent nuclear fusion or figure out AI. I have no interest in policy, no plans to join a think tank or get involved in politics. I find academia sterile and its writing style insufferable.

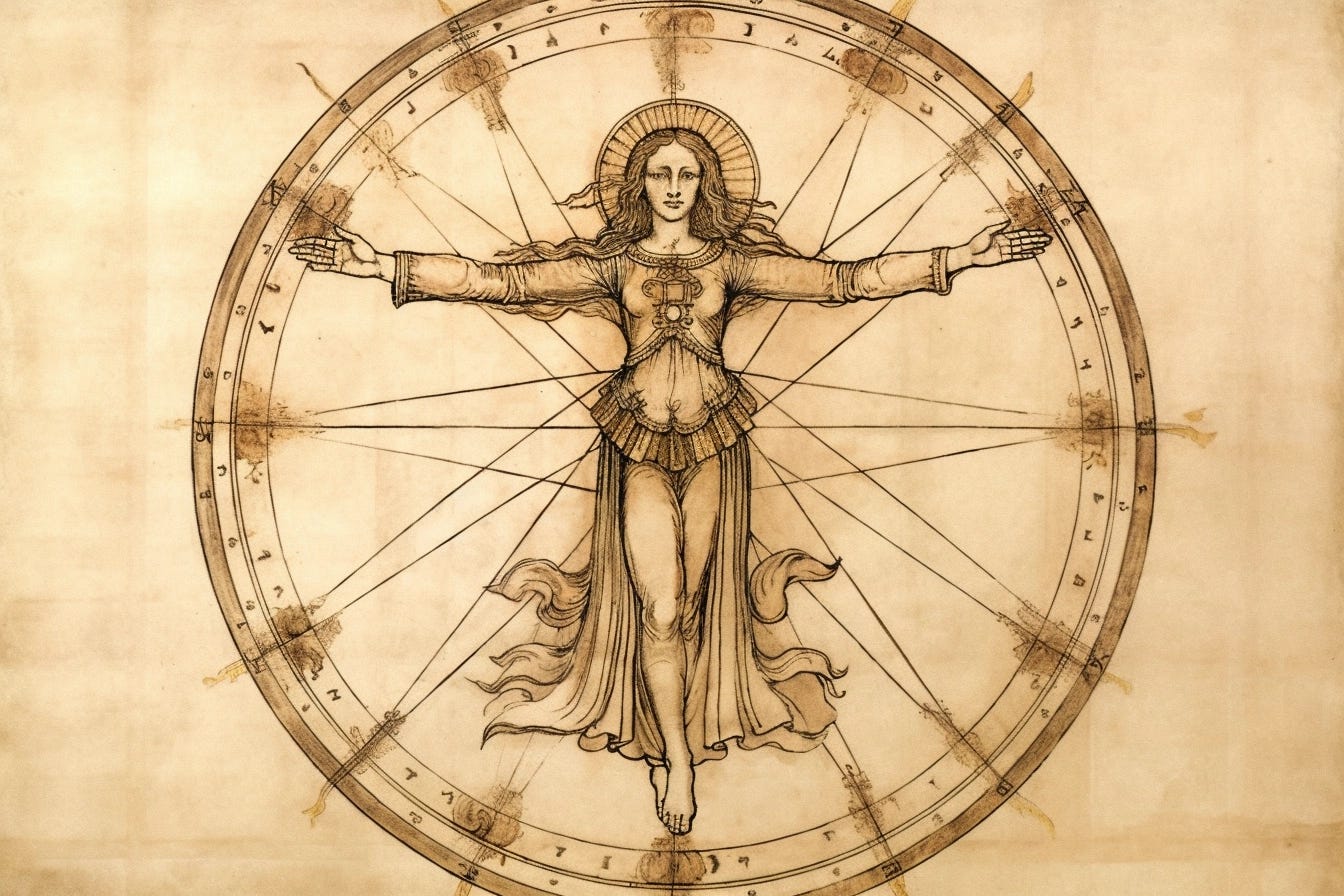

But that night, in the room with the piano and the singing, I was haunted by a vision of the Renaissance, when intellectuals were doctors as well as painters, architects as well as clergymen. Leonardo da Vinci was the ultimate “Renaissance Man,” a polymath who was an engineer even as he was a sculptor, an astronomer even as he was a painter. His interest in anatomy led him to dissect bodies to discover their cause of death even as he invented musical instruments, mechanical bobbin winders, and a steam cannon.

The French author François Rabelais made fun of the humanist predilection for self-mastery. In his satirical novel Gargantua and Pantagruel, Gargantua implored his son to study Greek, Latin, Hebrew, Chaldea, and Arabic. He was to learn, “all of the beautiful texts of Civil Law by heart and compare them to moral philosophy.” He should study nature, “let there be no sea, river, or stream the fishes of which you do not know. Know all the birds of the air, all the trees, bushes, and shrubs of the forests, all the herbs in the soil, all the metals hidden deep in the womb of the Earth.” And he should be a man of medicine, and “by frequent dissections acquire a perfect knowledge of that other world which is Man.”

As Sarah Bakewell points out in her book Humanly Possible, he was one to talk. “In fact, Rabelais had mastered a fair range of these topics himself, being a former monk, polyglot, trained lawyer, and practicing physician: he produced scholarly editions of Galen and Hippocrates and had some involvement in at least one public dissection.”

A monk? A lawyer? A physician? And a humanist scholar and literary writer?

The idea that I could study law as easily as sculpture, and without any kind of academic training in either, felt foreign to me.

The year I graduated college, the film “300” debuted in the theaters. It was about the famous Spartan warriors who went head-to-head against the Persian Empire. When an ally becomes concerned that they brought more soldiers than the Spartans did, the Spartan general only smirks. He asks the professions of his allies—they are potters, sculptors, blacksmiths—then he turns to his own soldiers, every one of whom has trained their entire life to become a warrior.

“You see old friend,” he says. “I brought more soldiers than you did.”

The next year, Malcolm Gladwell came out with his book Outliers further cementing the notion that to master something you had to spend your life doing it. His book made the case that every successful athlete or musician spent 10,000 hours mastering their craft. If I wanted to be a writer, I calculated that I could achieve mastery in 13 years if I wrote for two hours every day, or I could achieve mastery in five if I made it my full-time job. I started writing for two hours every morning before work and began applying for jobs that would get me closer to writing for a living.

But I had other interests too: I completed my graduate studies in Mariology (the study of the Virgin Mary), I received my screenwriting certification from Sundance, I studied French, I designed a fashion line, I read all the classics and then all the utopian novels, I taught yoga, I took harp lessons for a year and ballet lessons for two, I spent all of last year in singing lessons and learning to draw, I learned to surf. I am not good at any of these things, and for a long time I was frustrated that I would never master any of them, that I couldn’t spend 10,000 hours on every single thing I wanted to learn.

The “master of none” concept haunted me until this year when I realized that Leonardo da Vinci himself would have worn such a title. As a generalist, mathematicians of his time didn’t take him seriously, neither did those more practiced than he in Latin. But his penchant for following his curiosity allowed him to scribble outside the lines and explore new frontiers that those limited to their niche would never see. The field of paleontology, for one, didn’t exist until the 1800s, but Leonardo studied fossils and made a full notation of them in his journals. His question was: “Why do we find petrified seashells on mountains?”

Leonardo ventured several hypotheses in his journal: Perhaps petrified shells grew in the ground organically? Or perhaps petrified shells were the former home of sea creatures carried to the top of a mountain by some biblical flood? He ruled both theories out after noting that the shells were similar to existing marine mollusks and thus must come from the sea, and determining that there were several times in history when sea levels rose to the height of mountains.

This wasn’t some academically funded research study, it was just observations jotted in his notebook, and yet today he is called The Father of Ichnology (the study of trace fossils) for them.

As I learned more about the “Renaissance Men,” the Outliers concept began to flip on its head for me. Mastery was never the goal of the humanists, curiosity was. They didn’t want to understand one thing, they wanted to understand everything—the world, how it works, how we could make it better. The “300” warriors died on that mountain because the only thing they knew was war. Perhaps if they had learned something else, they might have come up with a better solution.

These thoughts were swirling in my head as I got ready for San Francisco. After 12 weeks of online study, we were meant to come to our fellowship weekend with our 1-, 5-, and 10-year goals, and I still didn’t know mine by the time I arrived. But a letter from our mentor Heike Larson was sitting on my bed when I got there, and her words breathed life into them. She said I reminded her of Walt Disney, and it was like she touched a magic wand to my head and dripped enchantment into my bones.

Walt Disney was a Renaissance Man. At first, he was into drawing, then he wondered if he could bring those drawings to life so he started a film studio where he turned them into Mickey Mouse. He developed the first feature-length animated film with Snow White, and he followed his fancy into live-action movies, world fairs, theme parks, and robotics. The animatronic people in his “It’s a Small World” ride were revolutionary at the time—and very humanist!

Disney World was his pièce de résistance, an experiment in utopia and a laboratory where he could explore the future of technology. If he had limited himself to spending 10,000 hours drawing, he never would have done the rest.

The next day, we put our dreams on Post-it notes and stuck them to a whiteboard. I watched in awe as my peers put up ideas like “revive the US nuclear industry” and “get immigration reform through Congress” and “lead the worldwide deployment of small radiation-free nuclear technology.”

Did I tell you these were some incredible people?

Amidst this gathering of intellectuals, I had been tempted to see myself as someone who should physically change the world by gripping it by its politics or its corporations. But I had bigger dreams than that. A government might make life better for its citizens and a company might make life better for its employees, but a film could invite utopia into our hearts, even whisk us away into it for a moment. If my goal was to create a better future, I wondered if I could achieve it better with art and philosophy than with politics.

I wrote down a couple of ideas: Write a utopian novel, turn it into an episodic in the vein of “Rings of Power,” launch a publishing company that publishes utopian novels and a film studio that turns them into films, episodics, and video games. But I also wrote down some curiosities: I want to study humanist texts; I want to become fluent in French and Spanish; I want to learn how to sing and draw and do gymnastics; I want to travel and experience different cultures. Limiting myself to any one dream would only limit where I could go with it along the way. And maybe there are better dreams I can find just by following existing ones.

I still want to master my craft as a writer, but I’ve realized I can use this as a forum to learn just about everything else. That I can explore how we can better the world through academia and science and math and art and theater and books and film and video games—not limiting myself to any one idea, but following my curiosity through all of them.

At our next dinner party, I hope I’ll sing along with the rest, and that I won’t worry that I am merely a “master of none,” because I’d much rather be a dabbler of all.

Thank you for reading,

Marginalia

One note from the margins of my research:

I really related to River Kenna’s piece “Soul Making Scholarship,” in which his teachers keep trying to get him to write more like an academic. Finally, he gets one of his teacher’s texts and reads the line: "This hegemonic colonial influence precipitated the cessation of endogenous cultural production."

I stared at the page, reading it over and over again, thinking surely she was saying something very deep. From what I could tell, she was taking the most convoluted possible route to say "when the colonizers forced their own culture on the natives, the locals eventually stopped making their own art and culture." But that idea was a simple, and easy to say simply — so she must have meant something more by all these endless impenetrable sentences, right? Why else choose to write that way?

This is what broke me away from academia too!

Wonderful! :) Thank you for writing this. May we all have the right to pursue our multi-faceted dreams, and defy the societal pressures that try to force us into a specialist lane. This is a topic near and dear to my heart! I wrote my own reflections on embracing our inner polymath in an essay that made the rounds a few years ago:

salman.io/blog/polymath-playbook

I have much more to say on it, and compiled an outline of a bunch of writing around the tactics of it -- in other words, how to actually execute on multiple things without losing your mind. I hope to get started on that in earnest soon. Just had to finish my book of fables first :)

I had a chuckle over being haunted by the phrase "master of none". I, too, have worried about the same thing in regard to the 10,000 hours goal, particularly when I drop one passion to move to the next. However, I fully agree with your optimism and inquisitiveness and believe that these are the wellsprings of creativity. However did you come across such a fellowship? It sounds like a delightful group!