Humanism is my religion now

Thoughts on living a beautiful life.

I once asked two nuns why they took the veil, both said it was the clothes.

By then, I might have cited similar reasons for my faith. I became Catholic because of gothic cathedrals, canters that sang hymns into the spires, incense that drifted from gold censers, and yes, dramatically dressed nuns.

Mine was a romantic faith, more aesthetic than it was spiritual—at least at first—and that is very much by design. An essential teaching of the Catholic Church is known as via pulchritudinis or “the way of beauty”—it’s why they build cathedrals and invest in art and sing in choirs—because the Catholic Church believes you can simply fall into your faith through the absorption of beauty.

That’s very much how I did things. I loved how rich it all felt, how steeped in tradition, how ancient. I loved touching my fingers to water that had been whispered over, making the sign of the cross against my lips, reading some of the first words ever written about my faith, discovering illuminated treasures in the archives of the Marian library. A decade into my faith, I was finishing up my graduate studies in Mariology, the study of the Virgin Mary, when I had lunch with the nuns, my teachers.

Throughout the course of my studies, I became agnostic. It wasn’t a lack of faith thing, but a lack of source material thing. The further back I researched, the more I couldn’t get on board with all that was added to the Jesus story in the centuries after he died—I had effectively researched my way out of my religion. Ultimately, I decided that I did not believe Jesus rose from the dead or that he was God, and that ended my religion. But it did not end my practice of beauty.

Unfettered from the constraints of dogma, beauty was no longer the entry point to my faith, it was my faith. For my final project, I recreated eight iconic images of the Virgin Mary using modern photography. I wanted to recapture who Mary and Jesus were to their people and in their time (not what they became in the centuries after) and to use art as a medium for expressing how beautiful that was.

That’s also the story I wrote into my first novel. Obscurity centers around one portrait of Our Lady of Sorrows, a harrowing portent carried beneath the arm of my main character Severine in the prologue. Throughout the book the painting acts as a mirror, reflecting the inner journey of the characters who look upon her. At the beginning, Severine looks up at that portrait and sees a woman who mourns the sinful and she feels the weight of guilt upon her. But by the end, only the girl remains—the one who grieves the loss of her son.

Indeed, my own faith might best be summed up by the last part of my last chapter, in which Severine looks up at that painting and finally sees her faith as a much simpler thing, something far more beautiful than the world made it:

“Once, Séverine thought the Virgin Mother mourned the state of Séverine’s soul. That she saw a sinful woman and lamented her greatly. Now Séverine smiled at the nostalgia of such thoughts.

The Virgin Mother did not mourn for sodomites or hedonists, for gluttons or heathens, for sexual deviants or murderers. She knew nothing of sin and how it would come to be cast upon one another like stones, creating a moral high ground for the ones who threw them and a ceaseless guilt for the ones who received them.

The face now darkened with age was once a living breathing girl, the hands outstretched in prayer once rested on her growing belly, the mind that sought some meaning from the heavens was once bewildered by that small new life. The historical reality of the woman who once lived now lost to the artistic renderings of the woman they wanted her to be.

Her son had risen up against their oppressors and was annihilated for doing so, as was every man who had followed him and loved him—his life lost in the memories of the ones who were left among the ruins. Bodies that had fought for freedom. Minds that hoped to live free from persecution and to see in humanity not saints and sinners, but an even ground upon which they could build life together.

Séverine wondered what happened in the hundred years after the birth of Mary’s son and before their story would come to be written about. Were they words passed about on the lips of child soldiers? Murmurs of hope that they might one day defeat their oppressors? They failed, Séverine thought, for 70 years after her son's birth, the temple was destroyed, as was the movement they created and the cause her son died for.

It was only after that cataclysmic event, that their persecutors saw fit to resurrect it. To pull from the rubble some shadow of the truth and use it to make of the man and his mother a pair of martyrs, ones that would enforce the better behaviors of their adorers and adhere them more ardently to the regime who reigned over them.

But the movement the mother and her son created was not dead in that destruction. It lived on in the peasants and the rebels, in the enslaved and the oppressed, in the native and the immigrated, in the ones who rose up against the hands that attempted to silence them, in those who believed that an even ground could in fact be built, and strove underground to attain it.

The small flame that was sparked by a young girl and her son lived on in the hearts of la Nouvelle-Orléans and was lit in the soul of that city. A small recognition that though they might not be able to heal the world of its hardness, they could at least treat everyone around them with kindness and see in everyone the good.

In this, Séverine felt a peace. A freedom. She turned away from the mourning woman and walked out of the convent, determined to mourn no more.”

By the time I finished my first novel, I thought I would leave Catholicism for Buddhism—that my second novel would take on a decidedly zen bent—but now I know I left for nothing. There was no further faith for me to find. As best I can tell, we are a sparkling speck of creation spinning about an unknowable universe—I am in awe of that, but any attempts to define it are beyond me. By the end of my studies, I knew less than I did at the beginning. I could only conclude, like Socrates before me, “I know that I know nothing.”

It was then that I became more of a humanist, more of an epicurean—one of the nuns called me Confucian. No longer concerned with an unknowable universe, I decided to focus my efforts on this more knowable world and how we could make it more beautiful, and that is the ethos I’ve been exploring personally, as well as literarily. If Obscurity was the unraveling of my religion, then Oblivion is the knitting together of my humanism.

This has proved rewarding, if challenging. Religion is a rather defined thing, humanism not so much. Catholicism has centuries of doctrine, with footnotes outlining why they believe each thing and when they decided they did. This made my religion very easy to adhere to: There was a list of things to believe, a body of work to study, and a set of ways to practice it—and all of those things provided a firm philosophical blueprint my first book could follow or deviate from.

By contrast, humanism has no such definition. There is no body of work that defines it, no doctrine that outlines it, no set way to practice it. It isn’t even a philosophy so much as a general idea: that humans are the thing worth our devotion more so than any unknowable divinity. In this way, any beliefs I put forth are my own, any body of work I follow is my own reading list, and any practices I participate in are of my own design. I am informed, perhaps, by those thinkers that came before me, but also entirely without a blueprint save one I invented for myself: that I want to imagine a more beautiful future.

Imagining a “better” future might have been the easier thing, and the more directly humanist. Making life better for all humans is a worthy endeavor and the bulk of what my essays attempt to achieve. But it’s the “beautiful” part that moves me and that’s what my novel attempts to achieve. It’s perhaps the more grandiose of my goals—the epicurean twist to my personal brand of humanism. A better life might be inevitable, it’s certainly more noticeable. But a more beautiful life is not, it’s subtle.

This is the point stunningly illustrated by the movie Soul—one of the most philosophically aspirational movies I have ever seen, and a Disney movie no less! The plot follows an old soul (who has lived life on earth) who is trying to teach a new soul (who has yet to live life on earth) what is meaningful about life so that she will want to give it a try. On earth, the old soul was a jazz musician—that was his “spark.” When he sat at the piano he was transported to another world and that made his life feel beautiful.

But the new soul can’t find her spark as easily. She tries so many things but not one inspires her. At the end, we know why—her spark isn’t one thing, it’s beauty. And she experiences that from a leaf fluttering from a tree, a busker playing guitar in the subway, the banter in a barber shop.

I can relate to both the old soul and the new. The old because I often identify as a “writer”—it feels like my spark! But, like the new soul, I know it isn’t the writing that makes my life feel beautiful. Rather, it is a million little things—the way the ocean folds like a blanket, the velvet sofa in my living room, a pair of cashmere pants. Writing is just one way of noticing them.

The noticing is important. When I asked my Substack Chat community what made life feel beautiful, you said things like being with others, feeling loved, enjoying nature, sunshine, grandchildren, certain songs, a long walk, taking the eucharist. My favorite answer came from Sollemnia: Eating a piece of buttered toast.

To me, this is both the hope and the challenge of living a beautiful life—it is also the hope and challenge of writing a utopian novel!

It is hopeful because all of those things that make life beautiful are available to anyone at any time. No matter where you are in the world, no matter what your circumstances are, you can probably eat a piece of buttered toast and feel that life is beautiful. We don’t even need a utopian society to live a beautiful life—the utopia is available to us right here, right now.

But it is also challenging because there is a personal responsibility to that. Even if you are the most privileged person, living in the most privileged circumstances, you could just as easily eat a piece of buttered toast and fail to notice how beautiful the experience was. Even if we have a utopian society, it will always be up to the individual to notice it—and we could just as easily miss it!

In the movie Soul, the old soul does miss it.

The new soul keeps coming up with ideas. “Maybe sky-watching can be my spark. Or walking! I’m really good at walking!” she exclaims.

“Those really aren’t purposes,” the old soul responds. “That’s just regular old living.”

But it’s the regular old living that can be beautiful—or not. And that’s up to each of us—or not!

After reading through Plato’s Republic, Thomas More’s Utopia, and William Morris’ News from Nowhere (more about these soon), I can firmly say that those utopian writers, had they awoken today, would find our current world (or at least many countries in it) a utopia! And yet so many of us today can’t. In fact, the better our society becomes, the more we fail to see the beauty in it. According to Our World in Data, the richer a country is, the more pessimistic it becomes about our future.

We’re probably too close to see it. Many living in London today, for example, might see clearly the challenges the city faces, but because they did not live in London 100 years ago, they are unable to see how far it’s come. In 1890, Morris described London as “'slums;’ that is to say, places of torture for innocent men and women; or worse, stews for rearing and breeding men and women in such degradation that that torture should seem to them mere ordinary and natural life." From his perspective, London today might seem a vast improvement—even a utopia. But from ours, that perspective doesn’t exist.

My own rosy optimism might be attributed to a similar juxtaposition. Societally, because I’ve spent the past decade studying Catholocism, reading 18th- and 19th-century literature, and writing a gothic novel that takes place in 1792; and by comparison, modern life feels pretty peachy. Personally, because I spent the decade between 15 and 25 severely depressed and suffering from PTSD and anxiety after a bout of trauma; and maybe it’s only by comparison that everything is coming up roses.

Today, I live in my dream house, I have my dream job, I work remotely and travel the world with my dream husband, and my sisters are my dream BFFs. I live in the best time for humanity and I love imagining how it could become even better. Still, I don’t think my rose-colored glasses are a given—I choose to see it that way. There are plenty of people who have experienced similar traumas and still haven’t found happiness. And there are plenty of people who have experienced similar successes and wish they had better. There are also plenty of people who are exposed to the same facts about humanity and think we’re approaching the apocalypse.

And this is where, if past experiences might shape our present perspective, there is still a personal responsibility to shape it in the positive. To this day, I see my mind as something I can spiral up or down, and if I notice my thoughts descending in a negative or critical direction I’m quick to change course and see the beauty in it instead. Here you can see my Epicureanism showing: if the stoic stands in the ocean and lets the waves roll over her without emotion, the epicurean stands in the waves and is overcome by their beauty—and can’t help playing in them! Even if we’re both experiencing waves, our responses to them are up to us.

From a world-building perspective, this is frustrating. As a utopian writer, I can dream up the most ideal society, one in which all humans have the resources they need to thrive, and even if we go on to achieve it, it will still be up to the individual to actually thrive—to notice that life is beautiful. I can lead a horse to drink, so to speak, but can’t make them drink.

But in a way that makes my job easier. If I am unable to procure a more beautiful world, I am able at least to notice it—to bear witness to it. Far more important than designing a better society then, is the art of noticing that it already is—that the beautiful world might be available to us even before the better world might be—and that has become the goal of my novel. As a writer, the only thing I have to do is transport my reader to a moment of beauty, if only for the span of one chapter.

But now I’m overthinking things even further because: what makes someone experience beauty?

In Obscurity, my main character was haunted by her past, in Oblivion I wanted my main character to be free of hers—so I gave her amnesia. Elysia has no recollection of her past or how she came to be stranded on the shores of my utopian archipelago. My intention here was almost a Buddhist one—she is living in the present, by design. Her existence harkens back to the Swahili proverb: If you are sad you are living in the past, if you are anxious you are living in the future, if you are happy you are living in the present.

In the third chapter of Oblivion, a botanist named Wao gives Elysia some tea to help her remember. Instead, she thinks: “I was lost to myself and for that all the better. For there was no past to haunt me, no memory to inform me, no aspiration to climb toward, nor purpose to fulfill. I would simply live amidst the poppies forever. A child of the Elysian fields.”

But if I removed the past from my character, I didn't remove it from my reader. When I sent that chapter to FogChaser to compose the musical score for it, I was surprised when he sent me a piece that was stunningly beautiful, yet entirely melancholy. When I mentioned that, he said it was based on that line. “Part of me feels like Elysia maybe has some sadness as she discovers this new world (and isn’t quite sure where she’s from). But that’s just my interpretation, probably because I’m all emo.”

I love that art feels different on different people—but so does life! We are all coming at it with different experiences, different perspectives, and different choices about how we want to respond to things. We may be able to design society so that it is to the best benefit of humanity. We may be able to eliminate poverty and get everyone to a better starting place—where all humans are educated and have economic opportunity. But to get everyone to live a more beautiful life? I can’t design for that, no one can—that will always be up to the individual to achieve.

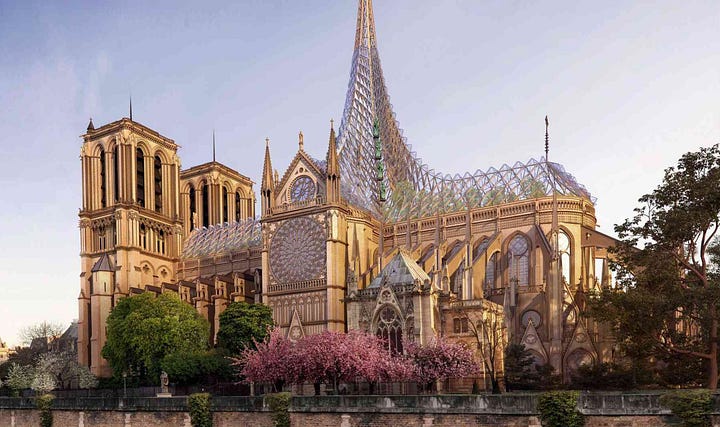

Personally, I left my religion around the same time the Notre Dame Cathedral caught fire in Paris. As I watched the spire burn, it felt like a symbol of my faith. As I wrote at the time, “to me, Catholicism is very much like her Notre Dame Cathedral in Paris: beautiful in its creation, yet crumbling with age and now catching on fire.”

Soon after, the architect Vincent Callebaut came up with a new design for the cathedral—one that would turn the spire into a garden and produce 21 tons of fruit and vegetables for the community each year. His was a new vision for religion, one that transcended spirituality to something more focused on humanity. “It is hardly enough to reproduce the past as it used to be; we must project ourselves towards a desirable future, conveying to the world the thirst for transcendence that propels human beings,” he said at the time. “Its pure and elegant architecture invites us to elevate our spirituality and adopt a much-needed and overly altruistic and humanistic stance towards the world around us.”

He called the project PALINGENESIS, a Greek word for rebirth.

Though they reviewed several designs for the future of the church, and the future of Catholicism, Paris ultimately decided to rebuild the cathedral exactly as it was before. The vestiges of that faith live on in subtle devotions—the medallions I wear around my neck, the art in my home—but I left the rest of my religion in those ashes, not just of Notre Dame, but of the temple that was destroyed long ago.

Now, I’m building Callebaut’s cathedral from scratch—one that transcends spirituality and is instead built on humanism. I’m still exploring what that means, both personally and literarily, but so far my scripture has become great literature and art, my practice has become the art of noticing how beautiful life is, and my evangelization has become sharing that beauty via my art.

I’m still hopeful for a better future, and I’ll keep researching how we can build it, but I believe a beautiful one is available to all of us at any moment—that the utopia is in our grasp right here, right now—that’s my religion. Whether you do too is up to you.

A person lives in utopia when they assume a state of merry.

—Utopia by Thomas More

Thank you for reading and happy holidays!

Elle

Beautiful piece. It is great to get your insights into what is driving the latest novel and its juxtaposition with the debut

Thank you for the shoutout Elle! I must admit, my utopian answers are entirely based on a simple question: what gives me joy when all of the humans in my life have worked my last nerve? Bread! Animals! Paramore!

This look into your spirituality was very interesting. Beauty itself is such a nebulous idea; trying to define it takes millennia. And so many definitions of it can exist at the same time! Catholic architecture and Islamic architecture are so beautiful but so distinct from each other. But beauty, like evil, is expansive. It can shapeshift into anything.

Maybe anything can be beautiful if it’s created with sincerity.