Maybe villages are our future—not just cities

Italy's Matera as a case study for revitalizing small governments and creating a future of interconnected villages.

Like many ancient Italian villages, Matera was once a thriving civilization that became abandoned for bigger cities with more universities and better jobs. The picturesque town perched upon mountain caves has played Jerusalem in more than one Jesus film and hosts only 60,000 residents.

There have been many attempts to revitalize Italian villages: Selling houses for €1 to attract international development or giving residents €8,000 to start businesses there. But Matera has been continuously occupied since the 10th century BCE, and the village saw an opportunity to do something different.

After all, they’d hosted great civilizations in the past, what new civilization could they still become?

“Because the city is very ancient, it is quite resilient—it has had to reinvent itself many times over the years,” Rita Orlando, Cultural Manager of Matera 2019 told me. “This seemed a strength on which to build a new vision for the future.”

In 2014, the village entered a bid to become the next European Capital of Culture—and won. The distinction is awarded to a new village every year, with villages submitting plans on how they will use culture to boost their development, and winners hosting a year of cultural events to attract residents and boost their economies.

Matera was especially entrepreneurial in its approach. They saw the competition as an opportunity to test innovative approaches to democracy and what the future of the village could become. They made everything open source, documenting their learnings as they went.

“Being a small city, in a small region of Italy which is not the center of the world, the only thing that made sense to us was to bet on disruption and innovation,” Orlando says. “We decided to offer the city and the region around it as a platform for experimentation. The city was offering itself to artists and thinkers and doers from all over Europe and the world to come here and find a playground to build new stories.”

Matera would host 2,447 events in 2019 and attract 500,000 visitors. They handed out passports to everyone who attended—a symbol of temporary citizenship—by the end of the year 40% of attendees were visitors, 28% were permanent residents, and the rest attended school locally or participated as sponsors and other affiliated individuals.

“It was a big big challenge for a city of 60,000 residents,” Orlando says. “Matera was pretty unknown. Then suddenly you are the center of the world stage.”

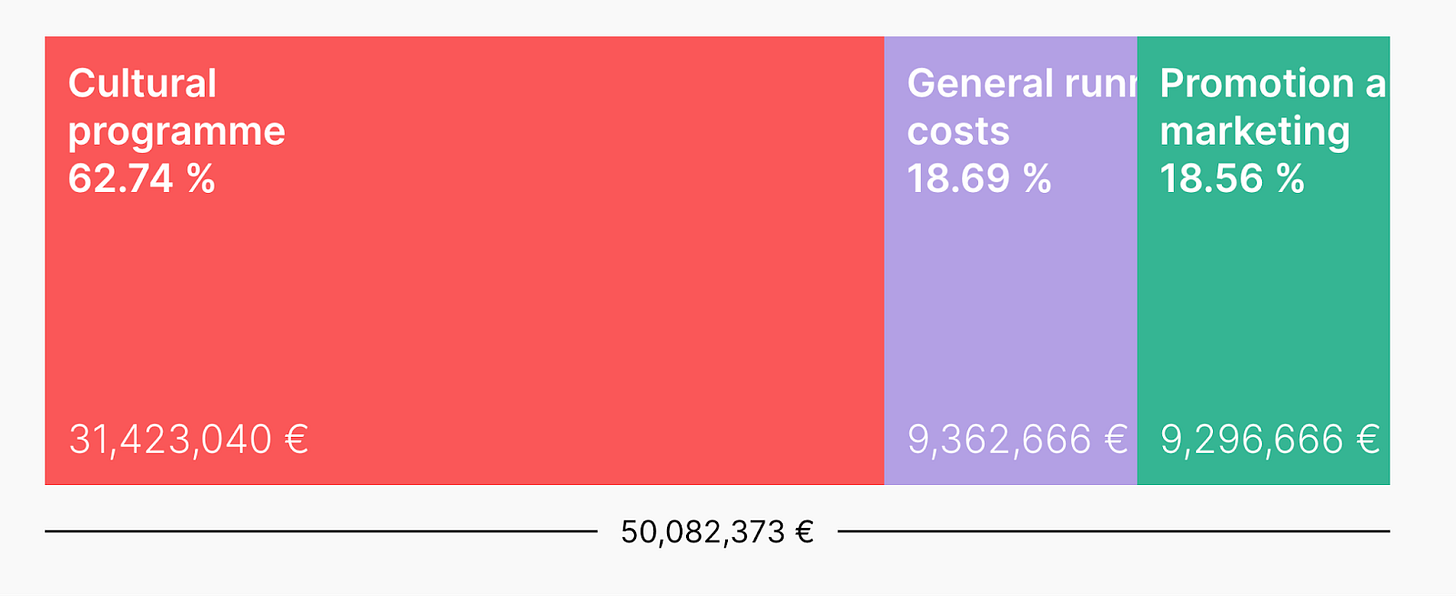

Being on the world stage came with a budget of €50 million—€20 million from the national government, and the rest from the regional government, with 6% from private funding—but Matera had an innovative plan for spending it.

“We invested all this money in culture, not on infrastructure,” Orlando says. “Only €5 million went to refurbish an old quarry that was transformed into a venue for performing arts. But the rest was invested in cultural productions, soft skills, capacity building, training for the cultural sector.”

This was a risky move. “Rather than buying blockbuster events to attract famous artists, we invested a lot in original productions, financing local cultural companies that were very small—2 or 3 employees,” Orlando says. “About €25 million was given to them to create original predictions. We produced 27 original projects. That’s the legacy that is still here.”

The town invested largely in what was already there: Local artists, local theaters, local museums. Imagine running a community theater with only a few volunteer employees, only to suddenly receive hundreds of thousands in funding to grow. Community members became entrepreneurs, hiring more people, creating more jobs, while producing cultural institutions the local community could enjoy.

“People have learned to face big cultural productions, how to work to engage communities, how to develop new audiences, how to develop entrepreneurial skills,” Orlando says.

The 2019 project tracked every one of their efforts in real time, documenting their successes and failures. A comprehensive review of the year found that people living in the village valued the cultural events and wanted them to continue. In fact, it was more important to them that their village be alive and thriving than it was to merely have good jobs and better transportation.

Matera was already a success story by 2019. In 1951, Matera had only 30,000 largely impoverished residents until a government campaign cleaned up the village and removed squatters that were then living in its historical caves, relocating them to the city center. Throughout the 1960s to 1980s, they went on to open small manufacturing plants for textiles, ceramics, and food production, creating jobs and reinvigorating the local economy. They built housing, schools, hospitals, and public facilities that could support a population influx from neighboring villages.

By 2001, the population had doubled, the economy was big enough to sustain their burgeoning community, and residents could think beyond surviving—they could think about thriving. The local community turned to revitalizing the caves—known as the Sassi di Matera—and designated them as a UNESCO World Heritage Site. This led to increased investment in restoration and tourism, creating jobs in the hospitality and service sectors, and even leading to film production. That’s when Matera was ready to enter Europe’s bid for Capital of Culture.

The town saw the fruits of their labor when, during the pandemic, they came together to put on a performing arts festival. Italy had just come out of two severe lockdowns and the festival was the first time many left their homes. “Participation in this event was so healthy, people had the motivation to leave their homes and be part of something better, and that made them feel better,” Orlando says. “That’s the power of culture, that’s the power of participation. It’s creating a social chance to break isolation and solitude and really take care of each other.”

In the years since Matera has become a hub for arts and culture. During the event, gardens, village squares, private homes, shopping destinations—even hospitals and prisons—were commandeered as performing arts and events spaces. Citizens claimed unused spaces as “commons,” and artists from every continent came and created alongside them.

Cultural transformation of the village had spillover effects on the local economy. Tourism increased, of course, and this has been a lasting legacy.

But so did entrepreneurship, especially among the youth. Between 2015 and 2019, the number of businesses in the village grew at twice the national rate. A higher portion of the population were entrepreneurs in Matera than the rest of Italy. Employment skyrocketed.

This has made a lasting change on the village. “Young people go away, but they come back now, and they go back and forth,” Orlando says. “Especially artists and creatives who have been here since 2019, they continue to come back and work here locally. So there are a lot of human networks that are here. The situation has completely changed.”

It’s not just an economy of workers anymore. It’s an economy of entrepreneurs and artists—individuals interested in bettering their community through culture. “People from the community are ready to be part of the game in a way they weren’t 10 years ago,” Orlando says.

Inspired by Matera’s success story, Italy created the “Italian Capital of Culture” designation to fund even more villages. “It’s very small compared to the European Capital of Culture but it’s an investment the Italian Ministry of Culture is doing every year,” Orlando says. “They have a very small budget—about 1.5 million a year.”

That money drastically increased after the pandemic. In 2021 and 2022, Italy earmarked €1 billion from the EU recovery fund to rescue historic villages. Twenty-one of them, one from each of Italy’s regions, were selected to receive €20 million each. Some of that money has gone to vital infrastructure projects, the kind Matera had leading up to the competition like schools, grocery stores, and businesses; internet access; and infrastructure projects that would restore beautiful but forgotten town centers. But a lot of the funding has gone to investing in tourism.

“Italy is a strange country because a lot of cities look at Matera as a successful example, but not in terms of how we did it,” Orlando says. “Rather than investing properly on cultural innovation and impact, they are pushing tourist attractions.”

Orlando says this isn’t sustainable, and it won’t result in successful villages in the long term. If we want to revitalize old villages, she says, we need to invest money in the people who already live and work there and empower them to revitalize it themselves. Instead, many Italian villages are using the money to attract temporary visitors like digital nomads, vacationers, and pensioners. Creating a town of hospitality workers does nothing to restore a village except as a modern Disney Land for expats—a historic Italian village serving as an attraction to relive the past, rather than a place to build the future.

Matera learned this the hard way. One of the early projects they invested in was the “unMonastery.”

“The statement around unMonastery was that experts would come from all around the world, for four months more or less, work with local communities around some topic, fix some local problems. What went wrong is that they didn’t speak Italian,” Orlando says. “The group came here and didn’t even know each other.”

These “experts” came from all over the world with a vision for a sort of open-source, hierarchy-less democracy. Their online platform Edgeryders was a cooperative and digital community, and Matera served as their in-person case study. “It was not the first, but one of the few platforms online where you could really make an exercise of participation and democracy from people all over Europe,” Orlando said. “It was quite new at the time.”

But hoping a bunch of outsiders from all over Europe could solve the problems of an Italian village they did not live in was a nonstarter—not least because the group seemed more focused on their own anarchic ideology than any kind of Italian resurgence. In his book Everything for Everyone, Nathan Schneider recalls that one of the members “lamented on his blog that people had been reverting to talking about the laptops they’d brought as ‘mine,’” when theirs was a vision of common ownership.

Not only did the outsiders not know how to solve the problems of the town, but it stunted locals who depended too much on those outsiders to solve things. “People here were waiting for real solutions to their problems—it was a matter of wrong expectations and miscommunication,” Orlando says.

They learned quickly from their mistakes: Matera couldn’t invite outsiders to come in and solve their problems, they had to be empowered to solve them for themselves. “After 10 years, I can say that yes, the community is much more eager to cooperate on cultural projects,” Orlando says. “But it happens at the community level, it doesn’t happen at the political or institutional level.”

When I asked how other villages could replicate their model, and whether government institutions should give small villages of 60,000 people €50 million for cultural revitalization, Orlando says yes.

“I think medium-sized cities might really be the future,” she says. “Small, medium-sized cities could be a reference point for all satellite villages or towns, rather than having one really big city where people get completely lost.”

Matera, after all, remains small. Its goal was never to become the next Rome, its goal was to stand testament to the fact that villages are not just our past, but could also be our future—especially now that remote work has made them even more accessible. Matera’s revival did not involve ballooning into a big city, but quality of life skyrocketed. And that’s something more and more people are looking for.

“My takeaway is that investing in culture means investing in people’s wellbeing. When people are really engaged in something where they can contribute to other people, they feel part of something bigger,” Orlando says. “So you break isolation and wellbeing increases a lot.”

Orlando hopes Matera can be an example for villages around the world. That we will eventually create, not a bunch of city-states, but a satellite network of interconnected village-states. But we need to learn from their example and invest in communities from within.

“We have a lot of knowledge to share,” she says. “I’m sharing this knowledge as an expert for other people, because it’s the kind of knowledge you acquire when you do things, complex things, and learn by doing.”

For more information you can find Matera’s open data repository here.

Thanks for reading,

This essay is part of CITY STATE, a collection of seven writers exploring autonomous governance through an online series and print pamphlet.

Thank you for this. I’m not sure how this is sustainable or capable of being replicated given this involved a huge national investment into a town that had been designated a European cultural capital. I like the idea of the future involving interconnected economically viable villages and towns (I think 60,000 is more like a town or small city), and perhaps this story is inspiring

because it involves a town branding itself with its local history and culture and perhaps that sort of micro branding is how towns stand out. And I agree with Orlando that the strategy can’t just be tourism, so I would be curious to learn how small towns can become competitive in manufacturing or making or providing specific services for export….maybe one idea is a town develops a particular craft and then hosts digital nomads or people who want to spend a season learning that craft. Mixing tourism with economic production.

I love this so much. Russell Smith likes to say "start where you are," which has stuck with me. This is a great example of that, in Matera's decision to invest in empowering who is there vs trying to attract a magical outsider solution. Also undercuts our stubborn assumption that "growth" equals "success."