Mary Catherine Gebhard self-publishes romance novels through her website—and she can earn between $60,000 and $80,000 on a book—but she kept coming up with a problem: some of her books were big hits, others weren’t—and she had no way to understand which ones would succeed and which wouldn’t.

It didn’t seem like a good solution to just keep writing books and hope that one out of five would “make it,” so she came up with an innovative solution—a way to A/B test novel chapters before she even started writing the book. Through her website ReaperHouse, she now tests chapters for several book ideas at once—for an audience of more than 250 members (I’m one of them!). The best performing chapters get turned into a book, with MC serializing new chapters through her members-only website.

She does this, not only because she wants to see what works and what doesn’t, but also because she has so many book ideas in her head that she can’t decide which ones to write. She admitted to me over the weekend that she has a spreadsheet of more than 90 books she is currently writing—ReaperHouse helps her know which ones to pursue.

I interviewed MC about what has and hasn’t worked along her self-publishing journey—and how her new members-only website might be the future of fiction. Here’s our interview.

What have you learned so far?

I can make between $60,000 to $80,000 on a book, but the expenses I had undermined any profits. It really only takes about $5,000 to put out a book—this includes editors, proofreaders, and the book cover. The shock factor really only comes in when looking at my marketing expenses. Ads, blog tours, PR, they ate up 80 percent of my profits, and are almost entirely unnecessary.

These outrageous expenses are shared between too many authors. So many of us are on the same hamster wheel, pumping out six-plus books a year, just to reach some modicum of a profit. I did this, and it fried me. For an entire year, I couldn’t write. I have friends who want to quit because they’re still doing this. Authors stay on the wheel even longer, because their books are priced too low.

A PR company I no longer work with told me I was insane for pricing my book higher than $2.99— at the time, everyone else was at $2.99. When authors price their book, they should consider how much time and expense went into making it, and how much profit they hope to make, but they continually undervalue their books because they see other authors undervaluing theirs, aka everyone else is doing it. They think they can’t sell them higher because no readers will buy them.

I fell into the same trap I think every author falls into initially, which is that there is a very collective mindset of how you become successful within the author community. It can feel like you have to try and do everything all the other authors are doing. If that author is doing well, then if I just make my book cover their way, or hire this person, then it will lead to success. But how well is anyone really doing?

PR agencies made your first book a success. How did that work for you?

A PR agency I once used recommended a model for my cover. I spent $900 on that model, and it actually hurt my sales because all my readers hated him. I ended up changing it out. I get a lot of authors asking me for recommendations, whether that’s for PR, ad hires, influencers, or what have you. I always ask them why they want them, the answer is usually the same: ”everyone else is doing it.”

I’ve hired multiple PR agencies ranging from indie to more “legit” (i.e. those who claim to have media experience and have worked with big publishers and authors). Each of them had different audiences, and I (erroneously) thought: well if I get this book in front of as many eyes as possible, it has to succeed. And it kind of did.

The indie ones tend to charge anywhere from $350 to $600 a month and work within the indie community. The bigger companies were a couple thousand dollars with contracts that keep them on retainer for at least a couple of months. In my experience, indie PR companies tend to be bloggers or readers who get into the game after being in the community for a while. They help with anything from organizing blog tours/Instagram and social media campaigns to running your social media accounts, to Facebook group takeovers or running Facebook ads, or even doing a special promotion.

PR is kind of a catch-all term in the industry. You might get someone who has no experience, who maybe ends up acting more as your personal assistant, or you might find someone who has worked with all the big publishing houses, has big names under their belt, but again it comes down to the question: did they cause that success? What are you really paying for? Could you have achieved your goals on your own, or for less?

Early on, I thought I had a repeatable formula. I released my duet, Beast and Beauty and they were a total hit. I released them via Kindle Unlimited in 2017 and the first month I made $6,000 in royalties—for all of 2017 I earned $60,000. It continues to do well and has sold around 9,300 units now that I’m out of Kindle Unlimited.

That formula at a glance was:

Sit down with my planner, schedule an optimal release date based on things like when other authors are releasing, holidays, etc.

Reach out to my editors, cover designers, beta readers, proofers, and PR companies with deadlines (and then pray to the writing gods I don’t miss those deadlines).

Writing would take approximately three months from start to finish, including beta reading, editing, proofing, and formatting.

Things that needed to be scheduled with my PR companies were: cover reveal, title reveal, teaser reveal, and anything else worth promoting.

I would make a street team calendar each month so my street team knew when to post and what.

One of my betas was also a teaser maker, so she would mark lines that would make great teasers and would then make those. We would send those to the street team, who would post all over social media.

We’d give call-to-actions in those teasers like “add this to Goodreads” or “vote for this for best upcoming romance on Goodreads.”

All of this was part of the timeline: If the cover reveal was that week, the street team would post about the cover being revealed that week.

I did SO MANY giveaways. For example, for my book Stolen Soulmate, I did a “30 days of Gray” giveaway, where I did 30 days of giveaways to mark the release. For Skater Boy, I sent out surprise boxes filled with swag and advanced reader copies to random bloggers and readers. No one knew they were getting it, and once word got out, it spread.

That book had the most hype out of all my books—and it was also my biggest flop. All of my marketing worked to an extent. I got eyes on my books, I got buzz, but I still hit a major plateau because I was basing my book’s potential success on vanity metrics.

So I thought I’d done it, I found my formula, and I could just put out another book and it would do fantastically. But that next book was a total flop.

Your next book was a flop. Why?

Generally, each author uses their new book to tweak their formula—but based on what data? I have beta readers who read early versions of my book, and I thought that was solid data. If my betas liked my book, then so would everyone else, but their feedback is corrupt from the start.

You want unbiased, subconscious data—When does a reader share your book? When do they put it down?—but the entire time a beta reads your story, they’re aware of you.

So maybe you listen to reviews, these are people who actually bought the books without prompt, but which reviews should you listen to? Which one of these readers is actually your market vs. someone who picked up your book but really only reads sci-fi. And let’s say you do manage to filter out the right feedback, how do you accurately test and tweak your new formula?

So, I had an idea after my big flop. I researched popular romance tropes that had gone viral within the indie romance community—step-brother, anti-hero, etc.—what made them popular? It was the juxtaposition of two unlikely tropes. At the time, bully romance was hot, so I did a bodyguard-bully romance. I thought I could latch onto the momentum of bully romance, and juxtapose it with a trope that was the antithesis of bully. No one was really doing that yet.

The new bodyguard-bully book appeared to have been a hit, because it did well...for a time.

Heartless Hero was first released using Kindle Unlimited—back when I was still doing that (now it’s wide, as all my books are). It was released in October 2020 and had over three million pages read. I made $2,000 the first month, $5,000 the next month, and I could reliably count on earning anything from $2,000-$6,000 until June when it dropped into the $1,500s. It has been declining ever since. Not counting Kindle Unlimited sales, Heartless Hero has sold nearly 9000 copies

But in reality, something was off. It never achieved exponential growth. The real problem finally revealed itself when my ads stopped converting. Typically when this stage happens, most authors decide to do another book—my PR company even told me to write another book—but that’s bad advice because then you get stuck in this vicious circle of creating artificial momentum based on vanity metrics.

What I realized was my word-of-mouth engine wasn’t working. Why weren’t readers sharing it? Why weren’t they buying it? The solution was not to write another book, because the problem was that my product-market fit was off the entire time. The bigger problem here was none of what I did was data-driven.

I realized that none of my strategies really “worked” in the sense that I established a solid, repeatable formula. In my opinion, the way authors approach writing their books is broken. In the old way, I would finish a book, send it to betas, and get feedback. If it was a huge rewrite, then I’d have to delay and maybe lose preorders. It’s such a bad way to write a book. There’s no iterative, rapid-feedback process. There is no other industry that does it this way. Marketing, software, manufacturing, entrepreneurs—no one is doing it this way.

I’ve had thousands of preorders and sales for previous books, but I don’t view that as a success because retailers like Amazon, Kobo, and iBooks are such a black box that I don’t really know who those readers are. What’s more, because they’re such a black box, I don’t know what parts of the book were successful vs. what parts weren’t. I want to know where the reader stopped reading. Where did they lose interest? What parts did they share with their friends? I can’t reliably replicate success if I don’t know what caused it.

There’s also this big misconception among authors that it’s not the product that’s wrong, they’re just not marketing enough. They fall prey to the idea that “if you build it, they will come.” Many writers think you write a book, spend a ton of money on marketing, and boom, you’ll be successful. If it was that simple, all you’d need to do is take out a loan.

Now you A/B test your novels before you write them. How does that work?

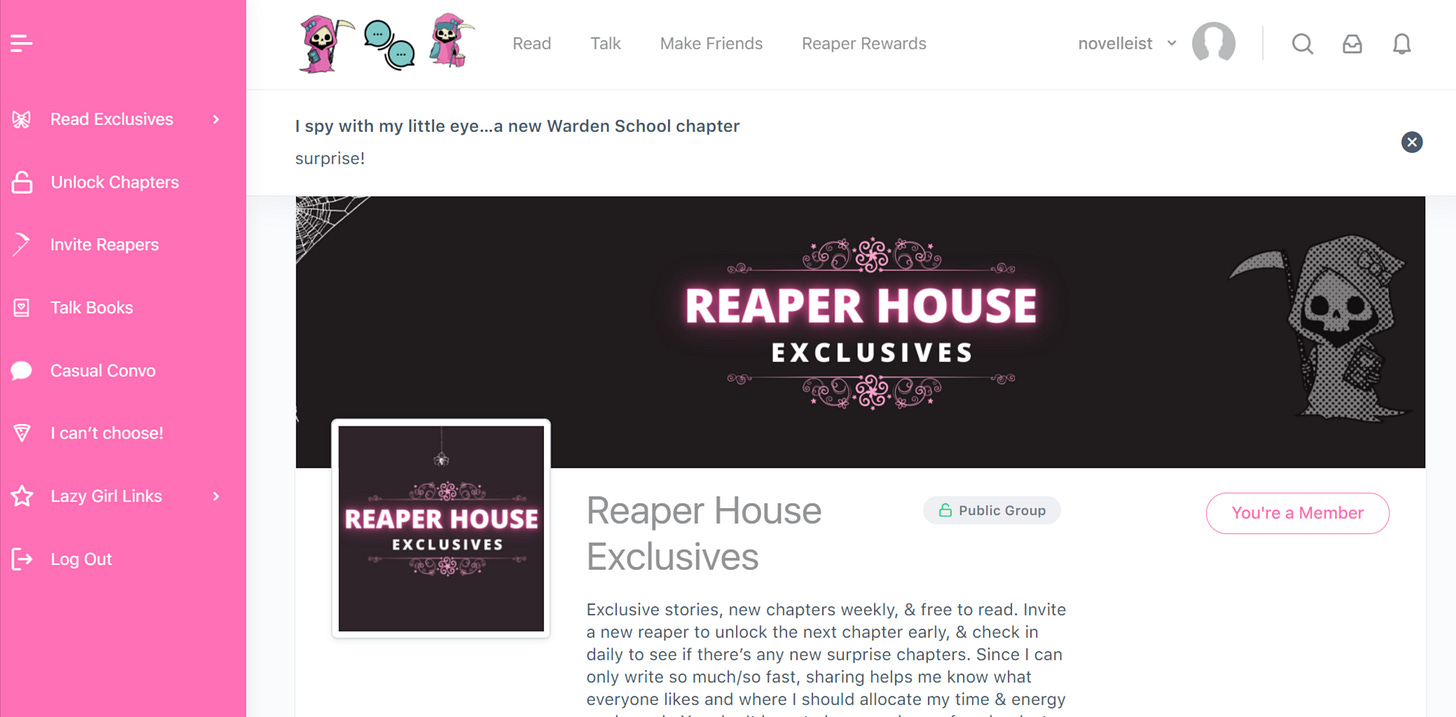

I created ReaperHouse, a website to interact with my readers and serialize and test my newest novels before publication. I designed it so readers don’t have to pay, but they have to do a little bit of work to get the story. For example, if they want to read the next chapter, they need to refer a friend. If they don’t even do that, then I know they don’t really want it.

Here’s how it looks on the inside:

Here’s how the discussion part looks:

Here’s a video of how the mobile works:

The whole point of ReaperHouse is to eliminate the questions I have as a writer when I publish. Which chapter would they prefer? Would they rather have this plot line or that plot line? Where did they lose interest? What part did they share? I’m using data to drive my decisions. If you ask a reader point-blank Did you like this part? Your data is already biased. Sure, they might like what you wrote, but are they going to recommend it to a friend?

Early on, I put the first three chapters of five new novels up on ReaperHouse and asked readers to invite friends to read their favorite novel—now there are 250 readers in there. The novel with the most invites wins, and it is now being serialized.

How it works is that I test different chapters and see which ones readers like the most. I’m only six chapters into my latest novel, and I already know that chapters four and five need work, because the sharing and comments weren’t up to par with the others. With that information, I was able to drive decisions for the upcoming chapters and set up an A/B test on my plot going forward.

I have 28 percent organic growth of new users, month over month. Engagement is increasing, and it all requires zero ad spend or seeding the pot. My work lies in developing, testing, and posting stories. Now I have a way to monitor, engage, and interact. If people stop reading I’m not freaked out, because I know what needs to be fixed.

What’s even better, is by the time this book is done, I should have thousands of readers already aware of this book. I should even know what my preorder numbers will be around, where before, I was basically spending money to get money.

Do you find it difficult to balance what you want creatively for the novel vs. what testers want commercially?

This is actually why I love Reaper House! I don’t feel like it creatively restrains me insomuch as it gives me more freedom.

Before, when I wasn’t sure where to go with a plot, I would stare at my screen while my brain yelled at me. Now, I can just throw up a chapter and test. For example, I actually have two different versions of the same novel up right now, Bancroft Manor. The first version of Banecroft is a gothic horror romance written in the third person and set in the 1920s. It’s very artistic, with an Alice in Wonderland vibe.

The second version is a dark fantasy romance written in the first person. It’s less artsy and instead harkens back to my taboo love story roots. When I started writing Banecroft, those two versions were vying for top billing in my head, and I didn’t know which one I wanted to give the reader. Instead of agonizing over it, I’ve put both up and am just A/B testing them!

This kind of A/B testing reminds me of the TV model of releasing a pilot, and the game model of play testing early builds. Nice to have some assurance the audience is responsive before committing to the full book.

Just fascinating. Like all your interviews, I love this one too -- not least because it gets down into the details of how this author is actually working (and selling) her books, and skips all the bland platitudes that are so common in pieces on how authors work in other places. Great stuff, Elle!