Obscurity, The Nineteenth Chapter

In which we learn the philanthropist's secrets.

We last read The Eighteenth Chapter, in which a missionary turned up dead and drifting in a canoe.

After breakfast, as the philanthropist reclined naked in his bed, his courtesan draped elegantly beside him, a servant brought him an envelope. It contained neither address nor return and must have been hand-delivered to his door. Even more curious, the wax seal was black and embossed with a crow, a crest that was yet familiar to the man.

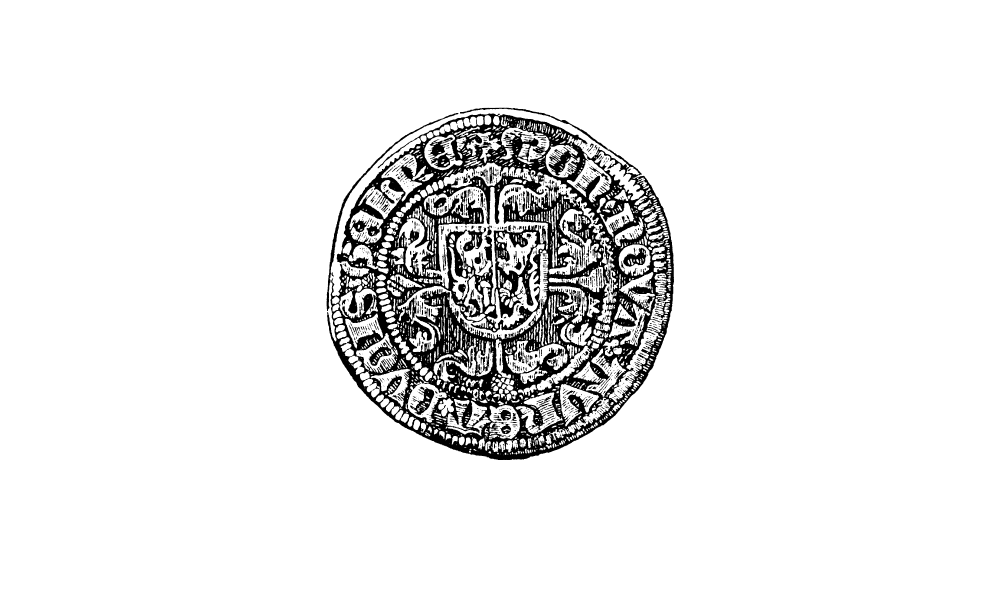

Tentatively, the philanthropist broke open the seal whereupon sweat instantly appeared upon his brow. Emptying the contents of the envelope, he felt the familiar weight of one Spanish doubloon in his hand. He looked at this token for a moment, his eyes closing intensely as his temples throbbed. Then, with sudden urgency, the philanthropist ran to his window and wretched over the balcony, passersby changing course to avoid his breakfast.

There was, in the southernmost region of Spain, a child without a penny to his name. The boy had no father and his mother had wasted away from consumption, so he stood on street corners and begged for morsels to eat.

At night, the elder urchins took advantage of him. They robbed him of what pittance he had earned and rendered his day for naught. Beaten down by a desperate lot and spit upon by passersby, the urchin wallowed in self-pity and doubt when he had the time to ponder it, and was consumed by the pain of hunger and the fear of death when he did not.

One morning, as if in a dream, the urchin caught sight of a man of great fortune who appeared as an angel before him. This man was important, the boy thought, a businessman. His clothes were made from the finest brocades and his hair coiffed in the highest fashion. When he walked down the street every man bowed before him and every servant rushed to greet him.

The businessman did not hunger or thirst. He did not demand the pity of his peers. With a cane in one hand and gold rings on the other, he commanded respect, passing the urchin by without a glance as he strode to his place of business. Even when he arrived at work, he did not step in the puddle before it, but upon a cloth placed carefully by a footman so as to spare his elegant shoes even a speck of mud.

Once the doors to his business had been closed, the urchin peered at himself in that puddle and, inspired by this apparition to change his lot, splashed water onto his face and into his hair, scrubbing away the dirt that had caked into his skin. In the evening, when all the town was quiet, he tiptoed into the courtyard, hiding in the shadows of the streetlamps as he pulled the rags from his body and washed them in the fountain. Then, finding the door to the baker’s left ajar, he snuck a heel of burned bread from the hearth.

The urchin hid himself in the doorway of a cathedral, laying his bread out before him as though it were the meal of a king. He would be like that businessman one day, he thought. He would work hard every day to be sure of it.

It was at this moment that the elder urchins found him. They pushed the child against the door and stole every crumb from his pockets, laughing at his combed hair and cleaned face as they kicked him to the cathedral steps and left him relegated to yet another foodless night.

The boy knelt in shadows of the cathedral and, catching sight of the saints carved into its recesses, he spoke his first ever prayer. “Dios mio,” he whispered. “Please make of me what you have made of that man. So that I might grow in favor and fortune and be spared my miserable lot.”

A lone tear fell to the child’s cheek, but he brushed it off with the bravery of a boy twice his age. He would not be forlorn, he thought. He would find a way to escape the fate of his parents and find a way to make something of himself. Finding these thoughts a comfort, he nodded off to sleep, his head bobbing softly against the church steps as he dreamed of a better life. One filled with pastries, and meats, and gold rings, and a cane, and the respect of a people who for so long had scorned him.

And who would one day would place cloths before him, so he might never look at another puddle again.

Through the window, the rector watched as the child fell asleep. He had seen the food prepared with such care, the rags cleaned with such devotion, and the tear that graced so delicate a face, and it brought the man to weep.

The life of a rector was a lonely one. For it held great power and great responsibility, and yet came without benefit of a person to share it with. God was meant to be that person, the Church taught, to be his most loving Spouse, and yet when his prayers ended each evening, his chambers fell silent and there was naught but the sound of his own breath to accompany him.

For close to a decade, Divine Providence saw fit to ignore the rector. During the day, when he was wrapped in the vestments of his order, the people treated him with all the dignity and respect his position afforded him and yet at night, they returned to their homes, warm in the beds of the spouses, and the rector was long forgotten.

Alone in his chambers, he cried out to the Lord. But there was no one to hear him when he spoke, no one to console him when his mind was troubled, and no one to hold him when he wept. God was but a ghost to him and the rector was left to face his lot alone.

At night, when the demons drew close, the rector thought of taking his own life. How beautiful it would be to die to this world and so awake to the next one, he thought. Oh, to be able to see the face of his Savior, to hear the timbre of His voice and live forever in the warm embrace of the One who loved him. To at last be listened to, and spoken to, and held. To have someone tell him time and again how loved he was—how cared for.

Alas, the thought brought him no reprieve. For in taking his own life, he would commit a most cardinal sin and thus become relegated to an even deeper corner of hell, where his misery would become his eternity. So, he lay in bed, alone and forgotten, living in the prison of his thoughts, waiting for death to come to him, until he happened to see a boy just as forlorn as he, and yet with so small and beautiful a devotion.

The rector wanted nothing else but to hold the child and to comfort him. Perhaps, if he had examined his soul properly, what the rector really wanted was for someone to hold him and to comfort him. But the rector did not examine his own soul and instead walked to the door, waking the child softly and inviting him inside for a warm meal and a hot beverage.

Wearily, the boy followed the rector to his bedroom, wherein both would come to regret the events that would occur there and would weep for what innocence was lost there.

Hate took root in the boy that day, and everyday thereafter. He became hardened to the world, resentful of the injustices of it, and scornful toward those reaping the benefits of it.

For 10 years he watched as parishioners attended mass at the cathedral, allowing the rector to place a piece of bread on their tongues and a drop of wine at their lips. How repulsed they would be to know the man’s own tongue was used for lechery, and his own lips for sodomy.

The boy had grown, but he could not conjure such memories without heaving the putrid contents of his bowels onto the streets. Passersby stepped aside him, more horrified by his defilement than they were of his defiler. They looked on the boy with disgust, while the one who was the cause of the boy’s misfortune they viewed with esteem. The rector profited highly from the praise of his parishioners and the fortune of their tithes and the boy was left to become bitter by his fortune.

During this time, the businessman seemed only to grow in fame and fortune, and he strode to his place of work each morning as royalty, untouchable by the commoners who would beg from him until, taking pity at the boy who slept in his own vomit, he tossed the child a single gold doubloon.

The boy had never held so much money in his hands, and yet he was repulsed by the gesture. He scoffed that the man saw fit to pity him. That he was only worth a pittance to a man for whom a pittance was made every minute. The boy’s bitterness made him bold. The next time he saw the businessman, he stepped forward, held out the doubloon and appealed instead for an apprenticeship. The businessman refused him, hardly glancing at so lowly a person as he continued to his place of work.

The boy persisted, meeting the man on his walk every day, and devising new reasons the businessman should see fit to hire him. After one year, the businessman finally looked at the boy, considering him for the very first time. Seeing a perseverance that could go unmatched, the businessman at last agreed to give the boy an internship and sent him along to the hiring manager.

The boy worked hard, earning himself the respect of his employer, and a wage that could provide him a small apartment nearby and enough food to fill his stomach. But it was not enough. He learned everything the businessman knew, and was even made an associate partner, but the boy was not content to be the businessman’s second—he wished to be the first. He wanted to be the one who pitied his employer, rather than the one his employer once pitied.

As the boy became a man, his hunger turned to greed. Knowing the business in its entirety and trusted by his superior to manage its finances, the young man waited until his employer was away on business, then he took every bank note from the coffers, bankrupting his mentor within an inch of his life save one gold doubloon that he left behind—the one he had been given so many years ago.

The one he now held in his hand as he wretched unceasingly over the balcony.

We next read The Twentieth Chapter, in which we meet the businessman once again.