Remote work could solve global poverty

Open the digital borders.

Let’s talk about this phenomenon:

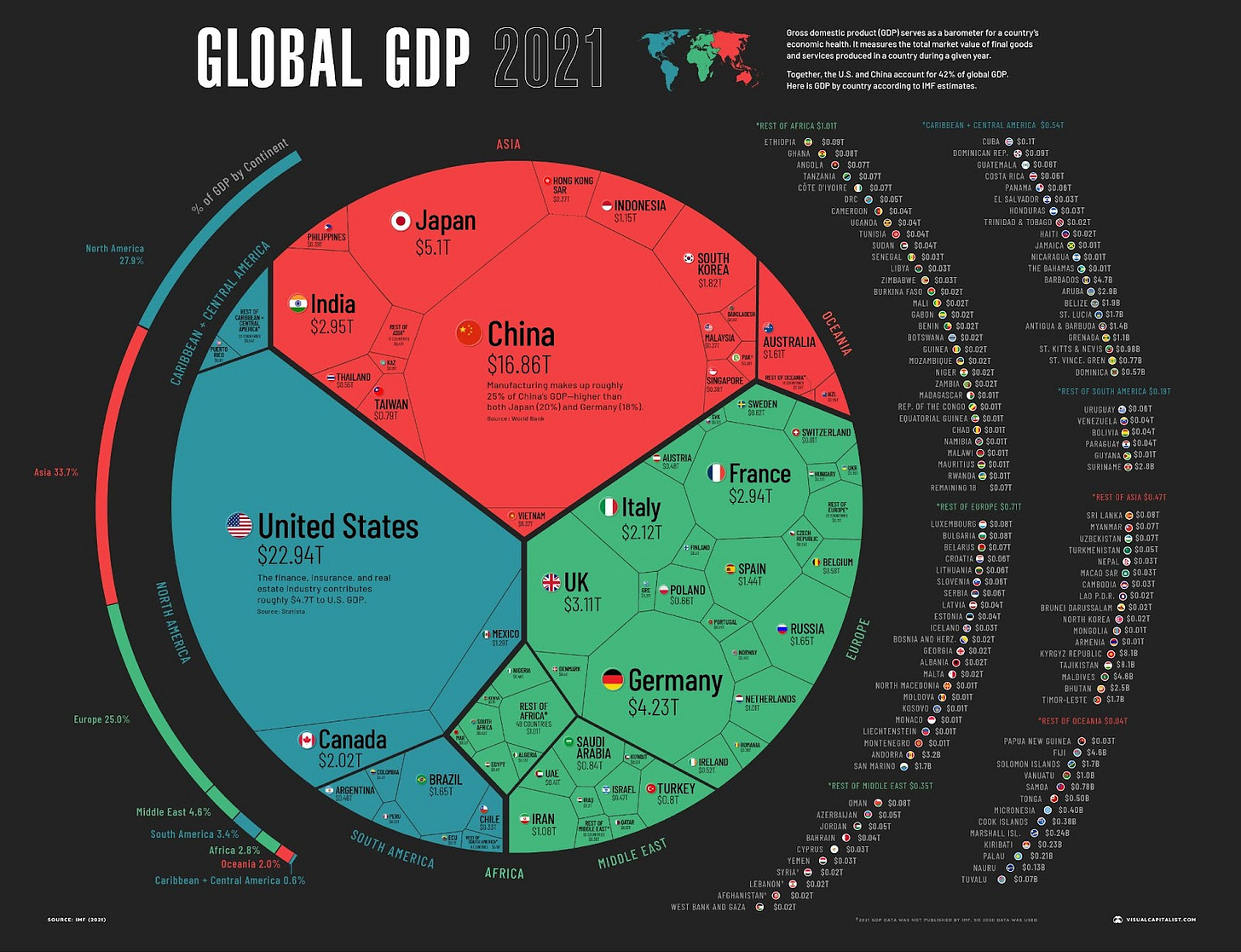

What that picture shows is the global GDP—that is the value of the goods and services owned by the whole world.

We can see that the United States, Asia, and Europe own a lot more, which means they are making more money, and thus their citizens have jobs and lower levels of poverty than anywhere else.

South America, though, is barely there, and Africa is straight-up absent. That’s two whole continents on our earth that have much smaller economies and thus have significantly fewer jobs and thus experience higher levels of poverty.

We talk a lot about eradicating poverty in the United States, and we should, but only 2.25% of our population still lives in poverty. In some countries that’s even lower—less than 1%.

Many countries have already figured out how to nearly eradicate poverty within their borders, and we should continue working on that. But close to 60% of the world is still impoverished.

And many countries are nearly 100% impoverished.

What can we do about that?

As I’ve written about before, one thing we can do is open the borders and allow people without economies to move places that do, instantly doubling their income while growing our global economy by 20-60%.

But another thing we can do is take advantage of trends in remote work and open our digital borders to international job applicants while paying them a wage equivalent to what they would earn in the United States.

That’s what Sahil Lavingia does. I’ve written about his “no meetings, no deadlines, no full-time employees” philosophy before, but his asynchronous remote work ethos has also enabled him to hire about 80% of his employees outside of the United States.

“I pay people $125 an hour US dollars, anywhere in the world,” he tells me. “Imagine if you are able to make the exact same salary or the exact same amount of wealth in Romania—where we have at least one person, maybe two—what does that do to the economy?”

Yes, what does that do to the economy?

Well, that person might spend more money on groceries, which gives more money to farmers. Maybe they buy a nicer house or pay to renovate it, which invests in their local community and creates jobs for contractors. They can afford medicine and doctor’s visits, which creates demand for more highly skilled positions. Their money gets invested in the local community, their wealth starts getting distributed.

If people are making enough money where they live then maybe they wouldn’t need to move to another country to support themselves and their families. Maybe they could stay in their own country and contribute to their own economy—maybe they’d prefer that. Sahil has offered to sponsor visas for his employees that do want to move to the United States, but many don’t want to.

“A lot of people do want to come here, a lot of people don't want to come here,” he says. “For many, the only reason they come to the US is to make more money or to avoid XYZ bad situation that happens less frequently in the US. But what if they could have just stayed in India and earned a living?”

And they could. According to a McKinsey report, 20-25% of workforces in advanced economies could work remotely. There’s still another 50% of the workforce that needs to be in-person, but even those jobs are on the decline thanks to automation.

“Job growth will be more concentrated in high-skill jobs (for example, in healthcare or science, technology, engineering, and math [STEM] fields),” the report says, “while middle- and low-skill jobs (such as food service, production work, or office support roles) will decline.”

As demand increases for high-skilled STEM positions, many companies are struggling to find them, leading them to recruit beyond their borders. Estimates show that the United States is short 3 million STEM workers and the world will be short 85 million tech workers by 2030.

The company Remote, which connects employers with highly skilled employees around the world, estimates that 30% of US companies are looking for hard-to-fill tech roles internationally, 25% of UK companies are doing the same, and 43% of companies in the Asia-Pacific region—which includes Australia, India, New Zealand, and Singapore—plan to hire 20-30% of their workforce internationally.

“Talent is everywhere,” Remote says on their website, “opportunity should be too.”

But getting those opportunities requires a very specific skill set. As Parag Khanna, author of Move, recently put it: “There are two global languages: English and code.”

Lavingia agrees. “If you want to participate in business you have to learn English, and you can't code if you don't know English. Because Python is written in English, JavaScript is written in English—we refer to it with English words. You have to speak the language to learn it… You almost need a startup school where you teach people these jobs exist and this is the stack: you need to know Figma, you need to know Notion, you need to know GitHub, etc.’”

With fluent English and skilled training, could places like Africa become beacons of STEM jobs? Of highly skilled labor? Could they take remote jobs for life sciences and tech companies and grow their local economies while they are at it? Because according to the African Development Bank (AfDB), 10-12 million Africans enter the job market every year for only 3 million available jobs and 75% of the continent is under the age of 35.

The president of the AfDB, Akinwumi Adesina, believes investment in better education could help Africans enter a global job market. “From artificial intelligence to robotics, machine learning, quantum computing,” he says, “Africa must invest more in re-directing and re-skilling its labor force, especially the youth.”

That’s why, in 2022 the AfDB debuted its “Skills for Employability and Productivity in Africa” action plan, known as SEPA. The program aims to raise the skill level of Africa’s workforce with the goal of “creating 25 million jobs and equipping 50 million young people with skills for productive employment and self-employment.”

It’s not just governments—companies are getting in on the action too. Google, unable to find the employees it needs, has launched free training programs in Kenya, Nigeria, and South Africa with the goal of creating 10 million high-skilled workers. They expanded their initiatives in 2022, committing to investing $1 billion in African entrepreneurs and startups.

Announcing a need for 3.5 million cybersecurity jobs globally, Google then launched a remote Cybersecurity Certificate Program, offering 2,000 scholarships for Africans. They also launched an accelerator program to incubate African small businesses. So far, Google has provided job training to 6 million Africans and trained 80,000 African developers.

Other countries have successfully reskilled their workforce. India launched Skill India in 2015. Israel and Poland invested in creating a highly skilled workforce fluent in English—that’s why Google opened campuses in both places. For a while, China was paying to get its citizens educated internationally—until it started losing them to those countries.

“The future is a meritocracy—you're getting paid based on your skills. Not your location, not your race, and not your degree either,” Lavingia says. “In theory, you're just getting paid directly for what skills you have and then the world will reform based on that. Apple HQ, for example, wasn’t architected by an American, it was architected by someone from the UK. Because it’s Apple HQ and they want to hire the best.”

If we can build a highly skilled labor market, the digital borders will be open but our actual borders will too. Canada is recruiting highly-skilled workers and opening immigration windows for them. Australia’s General Skilled Migration (GSM) program grants citizenship to skilled workers, so does New Zealand’s Skilled Migrant Visa. Germany’s Blue Card program targets non-EU citizens with specific qualifications and job offers.

There is a high demand for highly skilled STEM workers and that’s only going to increase, and there is a high supply of people around the world who could work them. If we could pair the latter with educational and training opportunities and the former with skilled employees then we could open our borders to one another and employ the whole world.

And maybe that’s one way we’ll solve poverty.

But I’d love to know your thoughts. Join us in the literary salon for further discussion:

Thanks for reading,

Elle

Marginalia

Here are my notes from the margins of my research.