The future used to be better

How contemporary art reflects our waning belief in progress.

This is a guest essay by Maarten Boudry. It is part of Terraform, an essay collection about the future of our planet. Support the project by collecting the digital or print edition 👇🏻

The Dutch artist Daan Samson has created a series of art installations he calls “prosperity biotopes”. These works are made in various mediums but share a common thread: The seemingly incongruous pairing of pristine nature and modern technology.

At his exhibition in Amsterdam, I spotted ants scuttling on an ant plant alongside a sleek steel Nespresso milk frother. It reminded me of the enigmatic black monolith from 2001: A Space Odyssey. Then there was a drawing on the wall showing a shiny electric dream car from Mercedes-Benz created by the African American designer Virgil Abloh, parked diagonally on a wild Bolivian salt flat, and flanked by sturdy cacti.

As an unabashed nuclear bro, however, I have to say my favourite prosperity biotope showcased a small modular nuclear reactor (SMR) from Rolls-Royce nestled right in the heart of the Congo Basin rainforest. Its sleek, hulking form resembles a steel caterpillar, its glistening scales half-buried in the earth, like a metallic version of the giant sandworms from Frank Herbert's Dune. It's the kind of utopian vision you often find in ecomodernist circles: High-density human tech—a single SMR cranks out more energy than dozens of square kilometres of solar panels—surrounded by pristine natural beauty.

By fusing the natural and the artificial, Samson invites us to think about the relationship between civilization and wilderness. Do we really have to choose between the splendor of untouched nature and cutting-edge technology, between majestic redwoods and towering skyscrapers? Or can we have our cake and eat it too?

Even more striking than Samson's welfare biotopes were the reactions from the art world. Some curators and art critics assumed his art had to be ironic and subversive. Was he slyly mocking our consumer culture and its tacky product placement? Or was he calling out the encroachment of human tech on Mother Nature? And wasn't there a hint of capitalism critique, lurking just beneath the surface? Art experts couldn't wrap their heads around the idea that Samson's work was genuine and carried a sincere, non-ironic message: We don't have to choose between nature and comfort—we can totally have both.

When Samson applied for subsidies from the city of Rotterdam, he received an unintentionally hilarious response. The city's cultural committee had decided that his art project was "preposterous." Why? The esteemed committee felt that the artworks "lacked critical reflection" and would have much preferred a "socially critical perspective on welfare." Loosely translated: If you want to make art in a 21st-century European welfare state, your work had better challenge modern welfare, mass consumerism, and neoliberalism. And if you're hoping to snag some government subsidies (a.k.a. milk from the capitalist cash cow), then you’d better be an enemy of capitalism.

For those who belong to the intellectual elite of a capitalist country, Joseph Schumpeter once noted, openly denouncing and condemning capitalism is “almost a requirement of the etiquette of discussion.” In the art world, it’s de rigueur to ungratefully bite the hand that feeds you. What’s that, an insolent artist celebrating modern luxuries and consumption? No dosh for this buffoon!

As a believer in progress, I’m loath to admit that anything was better in the past. After all, as the American journalist Franklin P. Adams once said, “Nothing is more responsible for the good old days than a bad memory.” But in recent years, I’ve reluctantly started to recognize that something has really changed for the worse. Pessimism and doom-mongering have always been with us, but over the past half century we seem to have completely soured on the idea of progress. Even so-called “progressives”, as I write in my new book The Betrayal of Enlightenment, have turned their backs on progress. Socialists like Karl Marx and Sylvia Pankhurst dreamed of a world of abundance for all and infinite growth, celebrating plentiful energy and denouncing the scarcity mindset. By contrast, many progressives today warn that economic growth is a dangerous fetish that heightens inequality and wrecks the climate, and constantly repeat the mantra that “the best energy is the energy not consumed.”

Plotting the evolution of the Zeitgeist is no easy task, but if you dive into the art and popular culture of the past, it seems our (near) ancestors were genuinely more optimistic about the future and more confident in modernity. The belief in progress—the continual betterment of the human condition—started to take shape in Europe from the eighteenth century onwards, when the steady accumulation of knowledge and innovation first became noticeable within the span of a single generation. For the first time, history felt like an arrow pointing forward toward the future: new innovations built on the old ones, and the old ones were never lost again.

This sensation of progress naturally led to a question that writers and artists raised almost immediately: if we follow the arrow‘s trajectory into the future, what will the world look like? The first futurists were, not coincidentally, also pioneers of the scientific revolution. If human knowledge continues to expand, they speculated, our descendants will surely live in a world of abundant prosperity, freedom, and beauty. The English philosopher Francis Bacon sketches such a society in his 1626 book New Atlantis. In this short story, published posthumously, Bacon describes a society on the fictional island of Bensalem in the Pacific Ocean. The harmonious community on this island is centered around the House of Solomon—a kind of research institution dedicated to investigating the world to obtain useful knowledge that can improve the lives of its inhabitants. The Bensalem islanders excel in "generosity and enlightenment, dignity and splendor, piety and public spirit."

The most famous title in this genre, from which we derive its name, is, of course, Utopia by the English philosopher and humanist Thomas More. Once again, we hear about a mythical island far away bearing the name Utopia, which can be read as a Greek pun. Literally, it means "the good place" (eu-topia), but it also means "no place" (ou-topia)—so, nowhere. If you want to be pedantic, the utopian books by More and Bacon aren't strictly about the future but about an ideal society in the present. Still, they describe a blueprint for a different and better society that we can bring into existence if we put our minds to it.

In the 19th century, when the Industrial Revolution was gaining momentum and socialism arrived on the scene, a whole cottage industry of utopian novels popped up, envisioning societies of technological perfection, universal prosperity, and brotherhood or sisterhood. The most popular title in that genre was Looking Backward by the American writer Edward Bellamy, published in 1888. The main character falls into a hypnotic sleep and wakes up 113 years later, in the year 2000, to find the society of his dreams. No one has to work anymore, everything is free, and hunger and poverty have been eradicated. 19th-century Europeans were thrilled by all of this: Bellamy’s utopian novel became one of the best-selling books of the century.

Partly in response to all these sublime dreams, the 20th century saw the arrival of the dystopia, the dark twin of utopia. If you try to create heaven on earth, the message seems to be, you’ll inevitably end up with a hellscape. It’s no coincidence that, unlike Bellamy’s forgotten reveries, the classics in this category are household names to pretty much everyone . You can make a fun quiz question about Looking Backward, but the authors of Brave New World and 1984 are dead giveaways for every educated person.

For a couple of decades, the utopian and dystopian traditions seemed to coexist more or less in balance, each feeding off the other. Up until the 1960s, you could still find optimistic visions of the future in popular culture and sci-fi. In the high-tech future of the iconic TV series Star Trek, which first aired in 1966, problems on Earth like poverty and war had been solved for good, making them unsuitable for plot material. The storylines in the original Star Trek seasons are mainly driven by curiosity and a thirst for adventure, with the universe as an endless new frontier beckoning intrepid space travelers. As the famous tagline of the starship Enterprise puts it: "To boldly go where no man has gone before!" Star Trek exudes the prevailing belief of the time in a bright future and a positive attitude toward technology.

In the same decade, millions of people tuned into The Jetsons, a futuristic TV series where folks zip around in flying cars and float on hovering platforms. Work was a thing of the past, every family had a robot housekeeper, and if you were hungry, you just pressed a button for a delicious meal! In 1967, CBS aired The 21st Century, a series where the iconic news anchor Walter Cronkite takes viewers on a tour of a twenty-first-century home. We see shiny kitchen robots, devices for medical self-diagnosis, and picture phones for video conversations. (Moral progress proceeded at a somewhat slower pace, as women were still confined to the kitchen.)

Newspaper ads from electric utility companies promised a “higher standard of living” tomorrow, all thanks to abundant power generation. Soon, we’d be gliding through the skies on “flying carpets,” powered by batteries. Just hop on, push a button, and off you go—no more parking problems! “They’re working on it,” the ad boasted. In a 1966 New York Times article titled “A Glimpse of the Twenty-First Century,” leading scientists predicted a world without deserts, dirty smog, or industrial noise. The human population was expected to swell to 25 to 50 billion, living in unprecedented luxury thanks to nuclear power and other futuristic technologies. Incredibly, this tenfold increase in global population was seen as a hopeful vision, not the impending catastrophe that later environmentalists would make it out to be. Stanley Kubrick's 1968 classic, 2001: A Space Odyssey, also captured that belief in the uplifting power of modern technology. Sure, the spaceship's computer, HAL-9000, goes haywire and tries to kill off the crew, but in the end human intellect prevails.

Fast forward half a century, and we can confidently say: Dystopia has eclipsed utopia. Twenty-first-century science fiction reads like a tale of a thousand-and-one nightmares. If we’re not wiped out by AI, then maybe it’ll be those predatory aliens. If nuclear war isn’t laying waste to the planet, then climate catastrophe will finish the job. And if, by some miracle, a few of us survive all this mayhem, we’ll probably wake up in a totalitarian hellscape—either trapped in a world of miserable enslavement (1984’s tradition) or stuck in a soulless, hedonic culture where every desire is fulfilled with a pill or the push of a button (Brave New World’s tradition).

In The Hunger Games, a totalitarian world government forces people to fight to the death in sports arenas by way of entertainment. In The Handmaid’s Tale, women are enslaved as breeding machines under a fundamentalist Christian theocracy. In The Matrix, a race of super-intelligent robots have enslaved humans and are literally sucking us dry as living batteries. The popular sci-fi series Black Mirror is the most inventive, as it presents a completely different future in every episode. I haven’t finished the latest season yet, but I’ve just tallied up the previous six seasons. Out of the 27 episodes, at most one belongs in the utopian category, with a straightforward happy ending. All the other episodes are pure nightmare fuel, usually involving some novel technology—from virtual reality to killer drones, from brain chips to surveillance cameras.

And how about other art forms? Up until the twentieth century, it wasn't unusual for artists to sing the praises of modern technology. The eighteenth-century poet and Enlightenment thinker Erasmus Darwin—grandfather of Charles—wrote epic poems in tribute to steam engines, grain mills, and blast furnaces. The elder Darwin even predicted the invention of locomotives and airplanes—and was quite chuffed about the prospect. In the 19th century, Rudyard Kipling wrote an ode to the steamboat, likening its mighty machines to a symphonic orchestra. Jason Crawford from Roots of Progress has collected such progressive poetry from days of yore on his website. You can read paeans to the Panama Canal, hymns to mighty hydro dams, and tributes to the telegraph and its inventor, Samuel Morse. After all, why shouldn’t there be beauty in human ingenuity? As the British journalist and philosopher G.K. Chesterton wrote in 1908, "Poetical," are "things going right."

Our digestions, for instance, going sacredly and silently right, that is the foundation of all poetry. Yes, the most poetical thing, more poetical than the flowers, more poetical than the stars—the most poetical thing in the world is not being sick.

Here too, this upbeat spirit persisted well into the 20th century. Some readers might still have childhood memories of it. In the visual arts, we had movements like Art Deco, Futurism, and Pop Art, all of which embraced a generally positive attitude toward technological progress and industrialization. Millions of people flocked to World Fairs to be wowed by the latest gadgets and industrial innovations. Even in the 1930s, when stormy clouds were gathering over the world, the World Fairs in Chicago and New York still projected hopeful visions of the future. In 1933, the exhibition in Chicago was dubbed A Century of Progress, with the tagline: “Science Finds, Industry Applies, Man Conforms.” In New York in 1939, visitors left the fair sporting cheerful blue-and-white pins on their shirts that read, “I have seen the future,” apparently without feeling ridiculous. Even after the Second World War, that sense of optimism rebounded quickly. In 1955, Walt Disney opened his theme park Tomorrowland with these stirring words:

Tomorrow can be a wonderful age. Our scientists today are opening the doors of the Space Age to achievements that will benefit our children and generations to come. The Tomorrowland attractions have been designed to give you an opportunity to participate in adventures that are a living blueprint of our future.

The American musician Donald Fagen—that oddball from Steely Dan—sang about that radiant optimism during the International Geophysical Year in 1957 on his 1982 album The Nightfly. The Cold War was experiencing its first thaw, and the East and West were set to work together to build a bright future for all of humanity, with a little help from science:

The future looks bright

On that train all graphite and glitter

Undersea by rail

90 minutes from New York to Paris

What a beautiful world this will be

What a glorious time to be free, oh

Yes, I know we should be careful to avoid the temptation to cherry-pick in this walk through modern history. Even in the glorious 19th century, as Jason Crawford admits, you could definitely find poems about the inevitable downfall of the West and the horrors of the "dark satanic mills," as the English poet William Blake described those coal factories. Likewise, there was no shortage of technophobic art during the Golden Years after World War II, or critics who abhorred consumerism.

And yet, something tells me that a century ago, a cultural committee might have been less surprised and dismayed by Daan Samson’s cheerful prosperity biotopes. As the Bavarian comedian Karl Valentin once said, “The future used to be better, too, in the old days.” Sometimes it feels like the best future we can imagine is one where we just avert some catastrophe or another. Or as Crawford put it with a sigh: “Today we hope, at best, to avoid disaster: to stop climate change, to prevent pandemics, to stave off the collapse of democracy.” A great example of this is The Ministry for the Future by Kim Stanley Robinson, one of the most popular sci-fi novels of recent years about the threat of global warming. Robinson's book stands out because, rare among climate novels, it has a happy ending of sorts. But don't get too excited: Robinson’s optimism mainly involves staving off total catastrophe. First, we suffer a few tens of millions of climate deaths and a series of gruesome attacks by climate terrorists. But just when things are about to turn apocalyptic, we're saved in the nick of time, after which the planet's thermostat is dialed back to the “stable” climate of the pre-industrial era. All's well that ends well. That's how stilted the imagination of even our "utopian" science fiction has become these days.

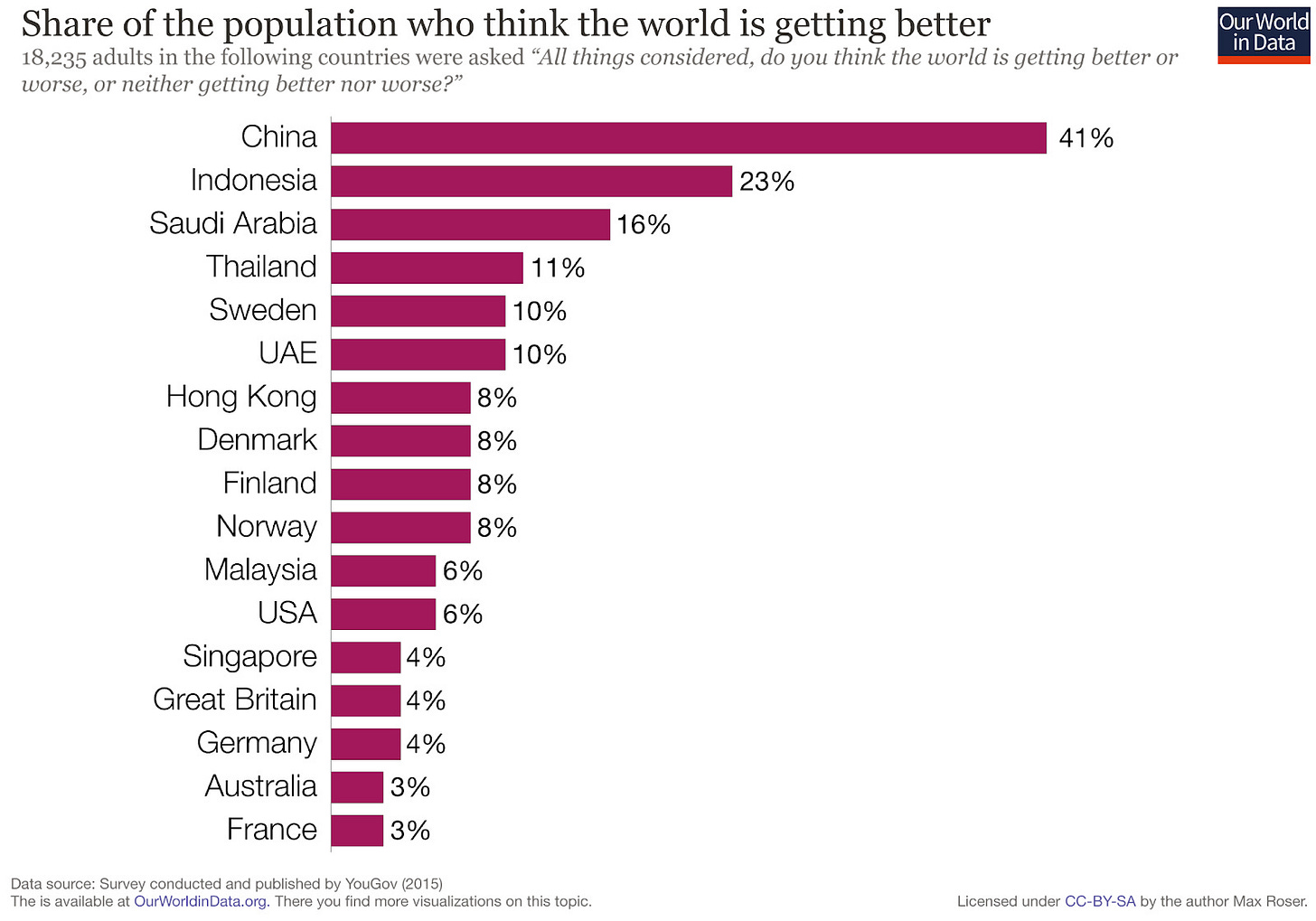

Losing faith in progress—and in ourselves—might come with dire consequences. Public surveys show something that should alarm anyone rooting for progress: in most Western democracies, less than 10% of people think the world is on the right track. And this was about a decade ago, when things arguably looked a bit brighter. What’s even more startling is that, in developing countries like China and Indonesia, the optimists make up a solid 41% and 23% of the population. A Pew survey from 2014 confirms that people in emerging economies are much more optimistic about the future of their children than in rich countries. I couldn’t dig up reliable historical data, but my gut tells me that belief in progress was at similarly high levels in the West around a century ago.

So, what happens to a civilization that gives up on its faith in progress? One theory is that we fall into the trap of a self-fulfilling prophecy. As the French-German polymath Albert Schweitzer once said: “Real progress is closely linked to the faith of a society who considers this progress possible.” It’s tough to measure the Zeitgeist over time, but if you just look at metrics like GDP growth, economic productivity, and innovation rates, you start to notice some pretty clear signs of stagnation. The economy is still growing, but it’s moving at a slower pace than in previous decades—especially in Europe. We’ve got more PhDs than ever, yet fewer groundbreaking discoveries.

If people lose their belief in progress and no longer see technological innovation as something worth striving for, then stagnation is what you’ll get. People will oppose new construction projects, governments will stop planning for rising energy consumption, companies will no longer invest in research and development— and art committees will snort at anyone who tells a positive story about technology and human prosperity.

To accelerate progress and innovation again, we don’t just need scientists, engineers and innovators. We also need a society that values progress. We need more artists like Daan Samson, who can show us the beauty and poetry in our modern industrial world, and who have the imagination to dream up even better futures. Seriously, can someone give this guy a grant to create more prosperity biotopes, please?

Very cool ideas here, thank you! I wonder if the loss of hope is linked to the greater availability of news and social media, which tends to skew negative. So we all get the impression that things are going downhill when they're really not, and then we project that image to our expectations for the future.

I find it interesting that you see higher optimism in China and Indonesia as a cause of their growth, rather than the other way around. Just from a personal narrative perspective, if you talk to people from these regions then they frequently frame their optimism in terms of having gone through a period where they have seen great strides across multiple generations.

The dystopian turn in the west at the start of the 21st century coincides with the emergence of a halting of improvement (or even reversal) in life quality for younger generations, measurable in terms of housing situation, social mobility, economic, political and environmental stability, and life expectancy.

The reaction to modern day aspirational artwork is very much tempered by beliefs emerging from material conditions. To me it very much seems Western people are losing faith in progressive beliefs because they aren't feeling the relative intergenerational material improvement that developing world people do.