There are so many geniuses alive today

We're just not noticing them the way we used to.

Samuél Lopez-Barrantes and I are currently studying genius by responding to Erik Hoel’s aristocratic tutoring series. Here’s the series so far:

Erik Hoel’s aristocratic tutoring series

Part I: “Why we stopped making einsteins”

Astral Codex Ten’s response “Contra Hoel On Aristocratic Tutoring”

Part II: “Objections to the importance of aristocratic tutoring”

Part III: “How geniuses used to be raised”

Samuel’s response: “On cultivating genius - part I”

Here’s my response.

The “geniuses” of Erik Hoel’s argument are the intellectually creative people who were philosophers, intellectuals, scientists, and artists. As examples, he cites the philosophers Marcus Aurelius, Bertrand Russell, Émilie du Châtelet, and Hannah Arendt; the poet Virginia Woolfe; the founder of evolution Charles Darwin; the inventor of the algorithm Ada Lovelace; and the physicist Albert Einstein.

All of these people were aristocratically tutored and so he concludes that was the best way to make geniuses. He even wonders whether we haven’t produced any geniuses since because we stopped aristocratically tutoring them. He says, “if I were forced at gunpoint to name the two greatest minds of the 20th century, I’d pick Bertrand Russell and John von Neumann. Is it really a coincidence that both were basically aristocrats?”

My counterarguments are a few: 1) That genius does exist today but that it doesn’t look like it did in the past, 2) that we are glorifying past genius at the expense of present genius, and 3) that we are confusing good quotes by dead philosophers for genius. If Hoel does a great job looking backward at all the “geniuses” of the past and determining how they were made, then I want to look at a few of the works of genius that exist today and determine how they were made. Spoiler: none of them were aristocratically tutored.

1. Genius still exists but it is no longer about one person having an “aha” moment

First of all, a lot of the geniuses mentioned by Hoel had big “aha” moments—discoveries that significantly advanced humanity like discovering evolution, antibiotics, the algorithm, or the theory of relativity. But we are very much still having big aha moments and making discoveries that significantly advance humanity. Here are a few examples.

In 2022 alone we launched the James Webb Telescope (which can see farther into the universe than ever before), finally created a breakthrough malaria vaccine (which will save so many lives), and have made huge advances in immunotherapy that have drastically cut down cancer deaths. We have figured out how to 3D-print skin and recently discovered the cause of aging and maybe even how to reverse it. Add to this fusion, the internet, the smartphone, and being on the brink of autonomous vehicles, AI, 3D printing, etc.—there can be no doubt that genius advances are being made all the time.

Do you know the names of any of the geniuses that were responsible for achieving all of that? Does that mean genius wasn’t involved? Or does it mean that we have evolved beyond the concept of genius as a person—one individual who reaches an “aha moment”—and instead have created teams devoted to achieving genius-like feats? Now, we are more likely to hear about the organizations who pull these off—NASA, GlaxoSmithKline, Apple, OpenAI—rather than the individual contributors who made it happen.

Let’s look at the James Webb Telescope, for example. After reading through the Wikipedia page I can find no one person who invented it, but there are many who contributed to it. There is Dan Golden, whose idea it was to use a larger beryllium mirror for the telescope. Then there is John C Mather who was the project scientist on the James Webb Telescope project. Either of them could probably be considered a genius—but everything they accomplished wasn’t one thing we could pin to either of them and say “here we go, the next most famous physicist after Einstein!” If it was, Hoel would have been able to mention these two men under the threat of gunshot.

“My child is not going to worship Kurt Cobain. My grandchild is going to worship the future!" —Dan Golden to an aerospace crowd shortly after the death of Kurt Cobain.

Instead, everything these individuals accomplished was the result of immense group efforts, and we are familiar with the group that achieved those accomplishments (NASA) more so than we are any independent work of genius. There are hundreds of other scientists who contributed to the James Webb Telescope just like there are hundreds of scientists who contributed to the malaria vaccine RTS,S/AS01 that will go down in history as one of the greatest life-saving cures of all time. The recent discovery of ICE, in which scientists discovered the source of aging and possibly how to reverse it, was published in an article with 64 authors and a footnote states that all authors contributed equally to the project.

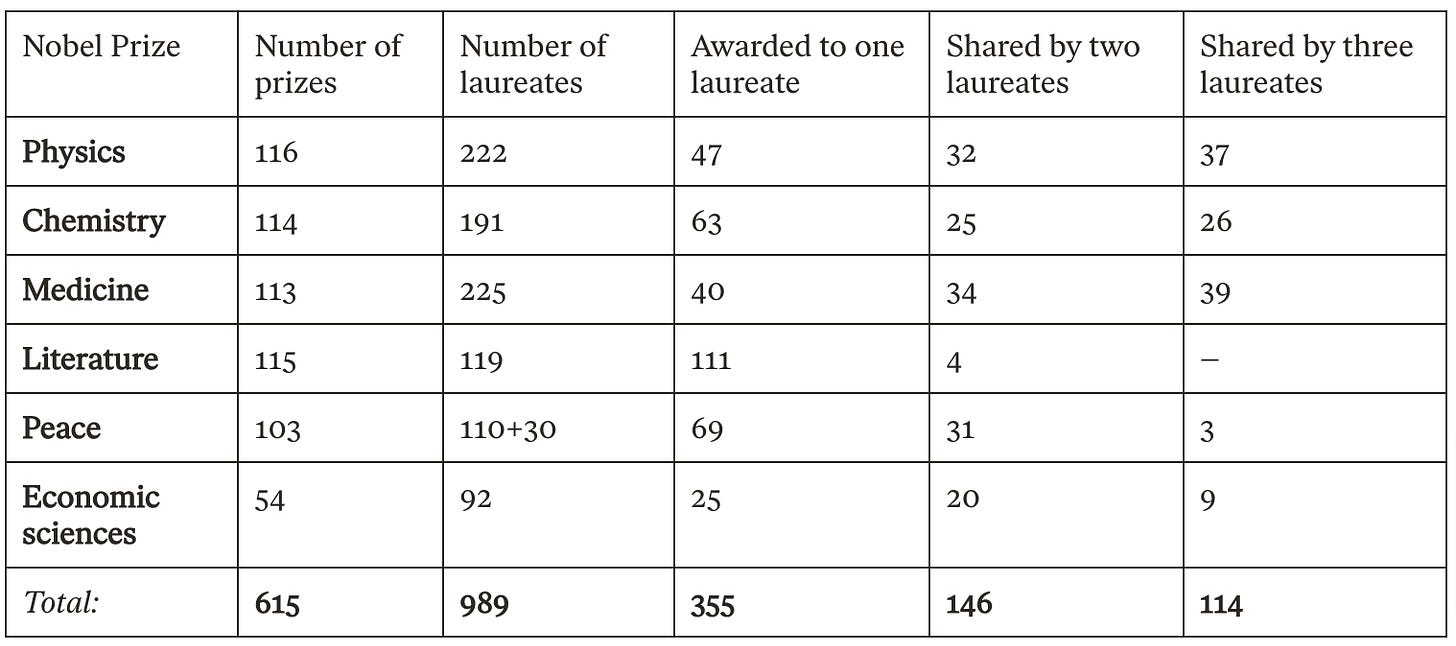

But let’s look at the whole lot—and by this I mean every single person who has ever won a Nobel Prize in physics. According to a 2018 paper in the Journal of Physical Studies entitled “Statistical Analysis of Nobel Prizes in Physics: From its Inception till Date”: “only 23% of the recipients were awarded individually and almost 77% had to share the prize.” As the findings conclude: “Among the individual prize-winners, most of them got the prize before 1950s and were primarily Europeans. The scenario changed in the post-WW era, where a ‘shared’ prize conception is found to be predominant, the USA grabbed about 39% of the prizes, including the migrants to the USA.”

As a reason for this switch, the paper cites that prior to the world wars Europe had very few researchers in the sciences, but had large funding grants. Then after the world wars, migrants to the United States “adopted a fascinating policy to have multiple groups of people (within the USA itself) to work on the same project at the same time. This led to similar mesmerizing results being reported simultaneously by more than one inventor; with the benefit that the results were cross-confirmed… Till date, the same trend has continued and there are hardly any scientists in recent decades who have been awarded individually, at least not in physical sciences.”

We are making huge advancements in science and technology but they are being done by teams with a prerogative to achieve them. There is not one person who made a discovery, but there are hundreds of people making discoveries on a regular basis and combining them to make huge gains.

2. We are glorifying past genius at the expense of current genius

In the creative arts, there are certainly more examples of individual genius. In fact, of the Nobel Prize categories (chemistry, medicine, economics, physics, peace, and literature), literature is the only category with more individual winners than group winners—as in, between 1901 and 2022 there have been 111 single laureates to 4 shared laureates.

Here though, the determining factors are subjective at best. I only recognized one person on the list of Nobel Prize literature laureates (Bob Dylan), though there are plenty more artists I would count as genius today—and many other ones you would. When I asked you to name modern works of genius from our own time frame, here’s what you said:

You mentioned Frank Ocean’s Blonde, James Cameron’s Avatar, J.K. Rowling’s Harry Potter, Drew Goddard’s Cabin in the Woods, Arundhati Roy’s The God of Small Things, Lorde’s Melodrama, David Graeber’s The Dawn of Everything, Quentin Tarantino’s Pulp Fiction, and Lin-Manuel Miranda’s Hamilton, among many others.

For the record, none of those artists were aristocratically tutored—most of them went to public school—though they did usually have some exposure to another artist that made them want to pursue art for themselves. James Cameron went to community college for English, but when he saw Star Wars in 1977 he decided to quit his job as a truck driver to get into the film industry. Quentin Tarantino worked in a film store and famously said, “When people ask me if I went to film school, I tell them, 'No, I went to films." Lin-Manuel Miranda decided to pursue musical theater because of Disney movies. He particularly fell in love with the crab’s musical number in The Little Mermaid—he even named his son Sebastian in part for that character.

Here though, none of that even matters because the barometer Hoel uses to determine creative genius is 100 years old. He doesn’t count Disney movies, Tarantino films, Harry Potter, or Hamilton among his list of literary geniuses. He names Virginia Woolf and says he can’t come up with a modern equivalent to save his life. I think this is less proof that geniuses were aristocratically tutored, and more proof that all the people we traditionally think of as geniuses were only alive when that was the kind of schooling that was happening. And also that we are biased toward past genius because of the whole “you can’t be a prophet in your own town” phenomenon.

I’ll never forget seeing Kristen Chenoweth in concert—she originated the role of Glinda in the Broadway production of Wicked but shared that she didn’t realize it was an important show until later in life. Growing up, she idolized Les Miserables—she saw it as a literary masterpiece while she sawWicked as just some piece of pop culture—a part of the zeitgeist. How could a song like Glinda’s “Popular” possibly compare to Jean Valjean’s “Bring Him Home”? It wasn’t until young fans started gushing about how Wicked changed their lives that Chenoweth realized that what Les Miserables was to her, Wicked was to them.

The film Midnight in Paris perfectly illustrates this phenomenon. Owen Wilson plays a screenwriter who moves to Paris to write a novel. As he struggles to become a literary great himself, he idolizes the literary greats who came before him and feels he could never measure up to the Lost Generation. That night, he finds himself miraculously transported to 1920s Paris. He attends a party with Zelda and Scott Fitzgerald and runs into Ernest Hemingway at a cafe. He encounters Gertrude Stein giving Pablo Picasso a review. Surrounded by the legendary artists he adores, Wilson is surprised to find that none of them think themselves great—in fact, they idolize the time that came before them: the Belle Époque.

Wilson then travels back to the Belle Époque. He dines at Maxim’s and attends The Moulin Rouge, he meets Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec, Paul Gauguin, and Edgar Degas. But they don’t recognize their greatness either—they’re struggling with their own attempts at genius and remain unable to see they will go down in history as having achieved it. The Renaissance produced all the great artists, they think, and their struggling Parisian lives pale in comparison.

I once asked Samuel whether we were unable to see modern feats of literary genius because it is written in all lowercase letters and peppered with emojis and I think that’s accurate. I do think that in 50 years, the young generations will look at today’s work and find them genius but that we can’t see it now because we’re glorifying the time before us.

3. We confuse good quotes by dead philosophers for genius

Here we must talk about philosophers. Because Hoel mentioned several in that category as examples of genius but neglected to count any modern thinkers among them. As I said in my post I’m so over dead French writers, I think we give too much credence to dead philosophers and not enough to alive ones. Especially considering the dead guys are operating off old assumptions based on outdated ideas while the alive ones have the advantage of expanding on what we’ve learned since then. Especially when it comes to utopian ideals and coming up with a more beautiful world.

Reading Plato and Thomas More and Francis Bacon has only confirmed my feeling that though their visions of utopia were visionary for their time, they are largely obsolete for ours. After them came Marx and women’s suffrage and industrialization and real-life experiments in democracy and communism that have further shaped our perspective on what would make the world a more beautiful place. Why should we give so much credence to Marcus Aurelius when there are modern thinkers among us who can expand upon what we’ve learned since then? A lot of what we’ve come up with is so much better than those philosophers could even have imagined!

Don’t get me wrong, Aurelius has some good quotes. But I wouldn’t rely on his worldview to get us anywhere today—for that I must turn to modern philosophers. I would count Erik Hoel among them, as well as Samuél Lopez-Barrantes, Tomas Pueyo, Étienne Fortier-Dubois, Jason Crawford, Deanna Kreisel, and many others. These individuals may not be seen as geniuses right now but that’s probably because of point two and three above. They very may well be seen as geniuses in a hundred years' time and then they’ll be saying it wasn’t aristocratic tutoring that created genius but online platforms like Substack that allowed it to proliferate.

Comments are open on this one, I’d love to know your thoughts:

Thank you for reading,

Elle

P.S. I intensely veered from your talking points Samuél, but I so agree with you about academics and their incomprehensible language. I have recently read several books in which that kind of intellectual babble went on for the entirety of the book. It’s frustrating because I get to the end and think: ok so what was this book even about?? In most cases, the plot can be summed up in a sentence but the filler is some kind of agonizing moralizing using only vague politicized terms—like post-capitalism, neoliberal, Keynesian, hegemony, Marxist, ordoliberal, communist, etc.—that are meant to confer a political stance and/or intellectual high ground but could also be used in a million different ways and are thus largely ineffectual at making any kind of point.

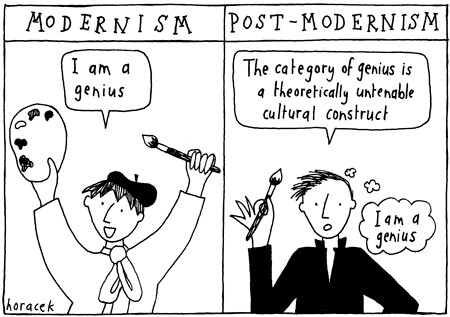

I also share your frustration about postmodernism in general. When I was trying to understand what postmodernism even was I read the Wikipedia page and still couldn’t get to the bottom of it. Then I found a cartoon that did a better job. I now take postmodernism to mean overthinking something to the point that it’s no longer relevant and I fear I may have taken an intensely postmodern direction with this piece probably to its detriment! 🤣

Couldn't agree more with you, great reflections. And the cartoon at the end was such a nice touch.

"Why should we give so much credence to Marcus Aurelius when there are modern thinkers among us who can expand upon what we’ve learned since then? A lot of what we’ve come up with is so much better than those philosophers could even have imagined!"

This way of framing the value (or not) of past thinkers already begs the question against them. Right Now is better, therefore the past is worse. Now where is your wisdom, Plato? <smugface>

The value in reading thinkers like the Stoics, and Plato and Aristotle and Cicero et al, is precisely because they put *our* modern views, including our humanistic assumptions, our natural equation of technology and science with goodness, and the very idea that history has a meaningful trajectory, into relief.

The fact that you can even judge today as "progress" against a prior state of affairs is entirely due to ideas you've received, without realizing it and to be sure through indirect means, from Plato and Aristotle.

I'd ask why incremental progress (James Webb, for example) is now wowing us more than the genuine revolutions in thought marked by Galileo, Newton, Darwin, Einstein, and Neils Bohr. It's easy to slag them off because we don't really get what upsets these were.

The same can be said for philosophers. A major figure like Kant or Hegel (responsible for Marx, by the by) really did bring about lasting changes in how the world looks. That doesn't happen when a lab tech patents a new gene-editing technique or a telescope sees a little better than the last one.

I don't mean to be harsh, but reading your list drove home to me just how *little* techno-science or artistic progress we make these days and how little it takes to amaze us compared to true table-throwing innovations of past thinkers.