We could return three continents of land to the wild

And create an interspecies future that benefits humans and ecologies alike.

This essay is the last in our TERRAFORM series, six writers exploring the future of our planet through an online essay collection and print pamphlet. You can still support the project by collecting the digital or print pamphlet for $5—both will publish next week!

Imagine walking through grasses as tall as trees, with flowers towering above you. There’s barely a path to meander through the abundant, ultraviolet meadow.

This is the goal of “Four Epochs of Paradise,” Alexandra Daisy Ginsberg’s four-story art installation that shrinks humans to the size of ants and invites us to participate in the natural world as insects do.

She wants humans to feel empathy for the natural world—for the insects and animals who live in the ecologies we destroy for our own wellbeing.

“The tapestry itself is a utopia, and it's an unrealizable utopia, although it could be realized,” Ginsberg tells me. “Imagine if we recreated this huge public space to prioritize other species.”

I first fell in love with Ginsberg’s work through “Pollinator Pathmaker,” an art installation she designed, not for humans, but for endangered bees, butterflies, and other pollinators. Gardens designed for people focus on aesthetic beauty, but bees desire certain UV patterns, and plants with nectar and protein-rich pollen. Hummingbirds look for red plants and flowers that dangle.

As my husband and I walked along the eleven beds planted at Kensington Gardens in London, and later pilgrimaged to her installation at the Eden Project in Cornwall, we found that gardens planted for pollinators were just as beautiful as those planted for humans, with the benefit of attracting wildlife, of creating biodiversity.

When we design for pollinators, we create spaces for them to exist. But when we design only for ourselves, we eliminate spaces other species can exist.

We’ve done that a lot.

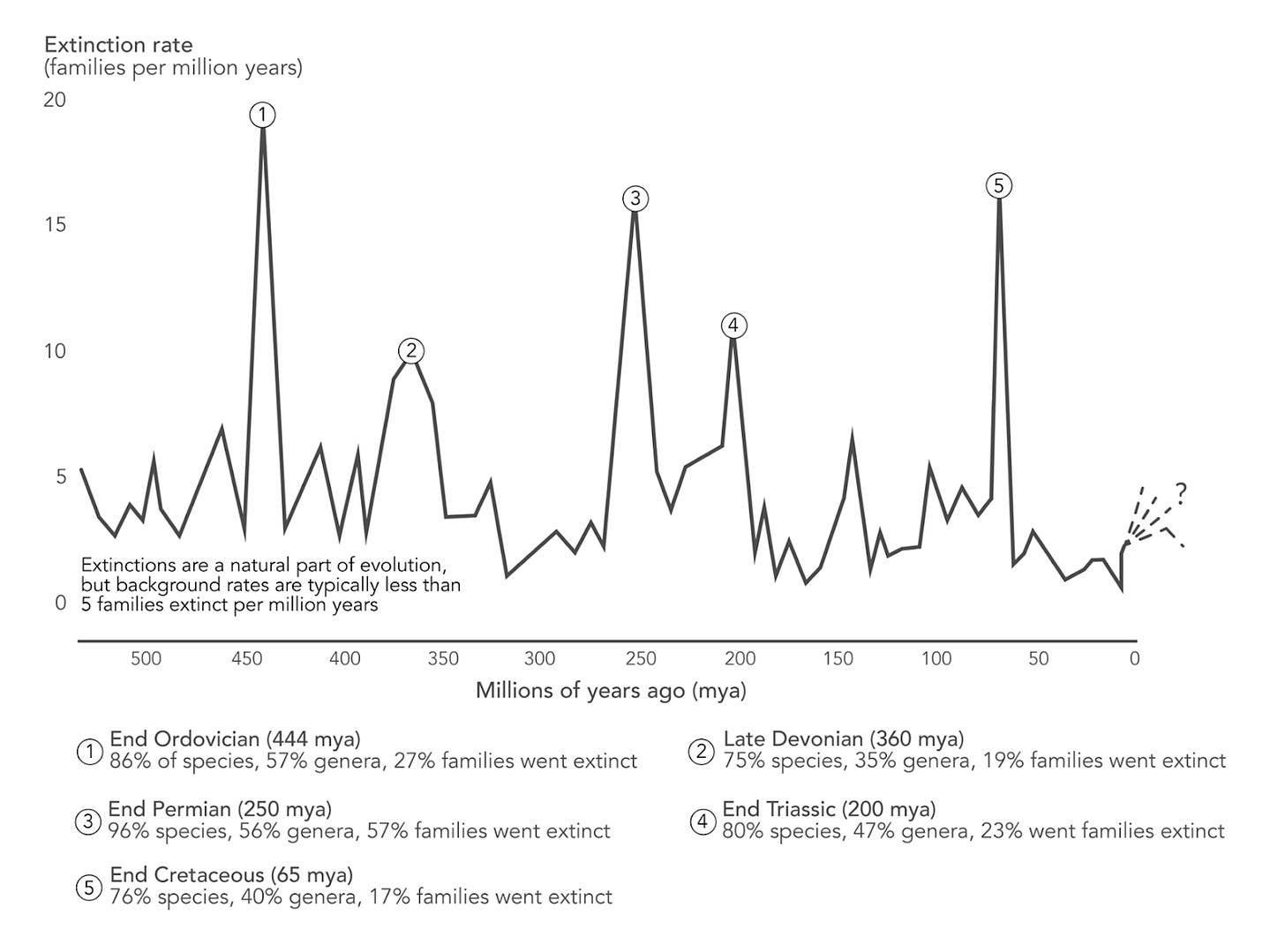

According to another UK resident, the researcher Hannah Ritchie, humans have eliminated 85% of the world’s wild mammals and half its plants. Extinction rates are now 100-1,000x the natural background rate, a level not seen since the last mass‑extinction event 66 million years ago. We haven’t reached a sixth extinction yet—we’d have to keep up this pace for 37,500 years to get there—but there can be no doubt humans have radically reduced the biodiversity of our planet, and in a relatively short time.

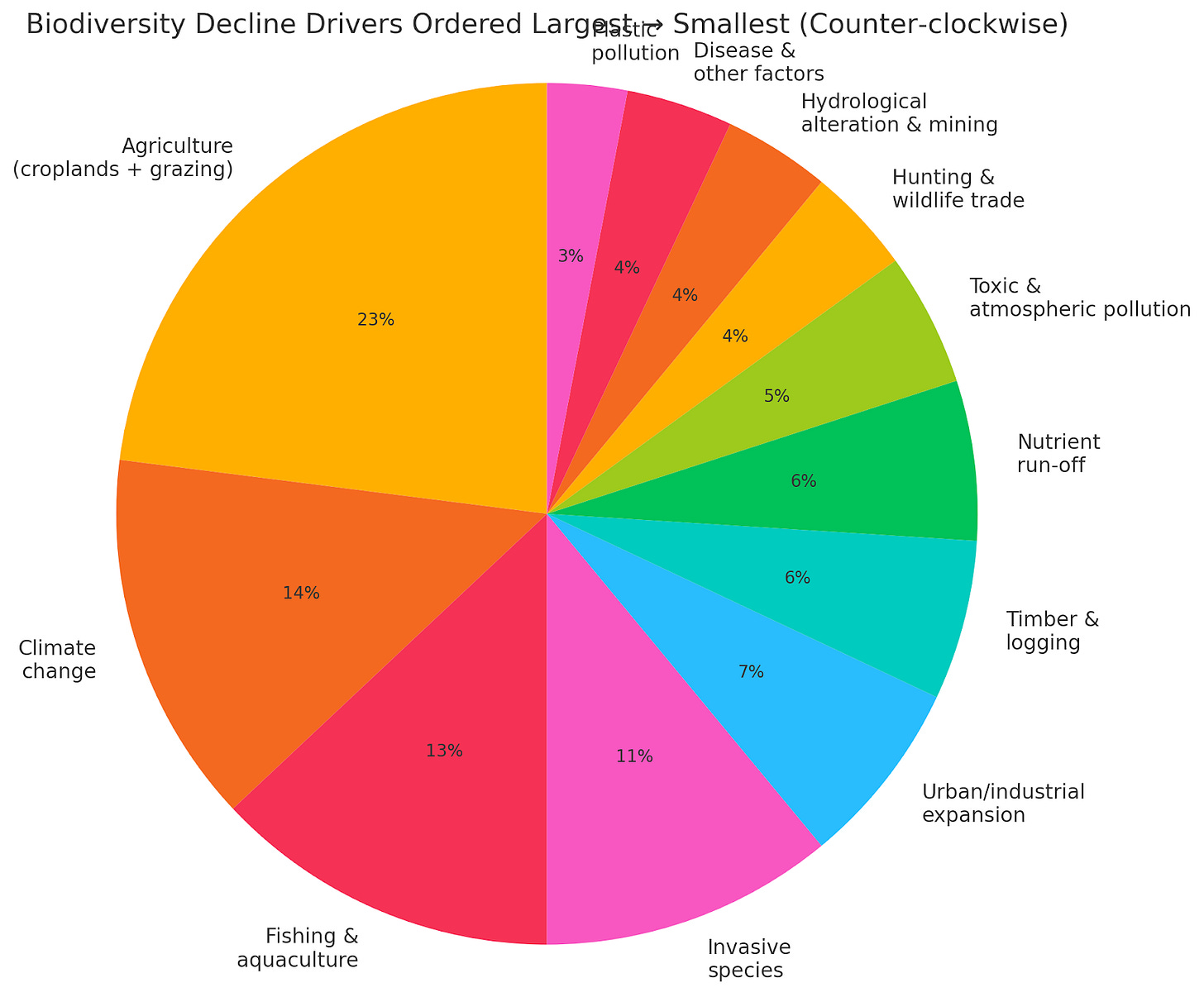

Most of that ecological loss comes from the way we eat—roughly 36% comes from farming and fishing. Agriculture currently uses one-third of the Earth’s land, with ecosystems cleared for crops and pasture. We remove more fish from the ocean than can rebound, and habitats are destroyed by methods like bottom trawling. The next largest cause of biodiversity loss, 14%, comes from the climate change caused by rising greenhouse gases—even then, 26% of that comes from food production, largely cow farming. The rest comes from energy produced by fossil fuels.

A lot of that ecological decline created massive benefits for humanity. Increases in food production reduced the famine and starvation that plagued most of human history. Life expectancy doubled, access to clean water and good food skyrocketed. Increases in energy consumption led to a decline in poverty around the world. Logging and mining helped us build things, and urban expansion provided city centers where we could live. Humanity became healthier, wealthier, and better educated. We destroyed a lot of the Earth’s ecosystems to get here, but we don’t need to do that anymore.

We know how to do it better.

Eighty percent of our agricultural land is used to raise livestock. In biomass, 62% of the Earth’s mammals are those we raise for our consumption, only 4% are wild animals (the rest are humans). We raise twice as much poultry than there are wild birds. Minor changes to our diets could return a lot of that land back to the wild. “Simply cutting out beef and lamb (but still keeping dairy cows) would nearly halve our need for global farmland,” Ritchie says in her book Not the End of the World. “We’d save 2 billion hectares, which is an area twice the size of the United States. If we were to cut out dairy too, we’d halve this land use again to just over 1 billion hectares. Three USA-sized farms saved.”

Eliminating the farming of cows and lambs would not only give us nearly three Europes of land back, but it would go a long way toward tackling nearly every other cause of biodiversity loss. We could rewild that land, replenish it with plant and animal life, and coexist in a world full of abundant life. Replacing fossil fuels with renewable energy sources could eliminate nearly the rest of our climate harm. With just a few tweaks to the way we eat and the way we produce energy, we could even grow the global economy 5x—creating a world of Scandinavian-like prosperity—while using much less land than we use today, emitting fewer greenhouse gases, and creating vast spaces for other species to exist.

We will still lose ecologies in the process—our future might not have rhinos or pandas—but that doesn’t mean we can’t still create a future in which ecologies thrive. In fact, an overfocus on the loss of rhinos, panda bears, and other large mammals has undercut the value of biodiversity to our species and led to an apathy about their disappearance. Ginsberg’s piece, The Substitute, explores “our preoccupation with creating new life forms, while neglecting existing ones.”

“A very extreme example is the attempt to resurrect the northern white rhino, of which there are only two females left, with a very elaborate scheme of doing IVF and using the southern white rhino as a surrogate,” she says. “Why would we protect those any more than the ones that we've already managed to render extinct? And how does that meaningfully contribute to the reintroduction of a lost subspecies?”

Ritchie also comments on the rhino: “Why are so many people dedicated to saving this single species? It doesn’t really make sense. It’s expensive to protect only two individuals, money and time that could be used in a range of other ways. Not least in trying to restore populations of the southern white rhino—its cousin species that is still going strong, but under threat.”

We don’t need the northern white rhino, we also don’t need the pandas. “We give disproportionate attention to the species that provide the least functional value (the pandas) and we ignore the species that really do matter for our survival (the worms and bacteria),” Ritchie says.

Remove pandas and the global ecosystem ticks on; remove soil microbes and earthworms and agriculture stops within a season. But it’s hard to get humans to care about the loss of worms and insects so we focus on the pandas.

Even that is not enough to inspire people to act.

“I live a hypocritical life, as I think most humans do,” Ginsberg says, “because we think about our long term future, and most people who agree with science will agree that there is a crisis that's only going to get worse, and yet we don't behave as if that's happening because we have a conflicting short term need to for survival, or just to have a nice time as humans, or to get through each day so we don't change our behaviors as individuals or societies overall.”

Humans might care about plants and animals, but we care about our own wellbeing first. Any threats to our survival are minimal and exceedingly far in the future. We might lose pandas and rhinos, but we gain cities where we can live and power that keeps the lights on. We might cut down plant and animal life around the world, but it’s so that we can grow food for us to eat. We might lose pollinators, but only a third of our food crops require them and yields would only decline by 5%. We might lose forests and mangroves and coral reefs, but an increase in fires and hurricanes and mudslides doesn’t seem too dire for what we gain.

It’s much harder to recognize all of the ways an interspecies future would be beneficial to humans. A quarter of prescription drugs and 40% of pharmaceuticals are plant-derived, including cancer treatments. We are losing plants faster than we can study them, with 93% of plants still unstudied and their potential untapped. While we live safe in our homes, with more food than we can eat and heat and air conditioning that assure our every comfort, the parts of the planet that don’t as much farming or use as much energy can’t avoid the worst effects of the ecological suffering we cause.

Importantly, the aesthetics of nature are fundamental to human flourishing. When we add trees and plants to our cities, they become abundant, desirable places to live. Our markets agree: For every 10% of tree cover added to a neighborhood, there’s a corresponding 0.5% increase in real estate prices. Houses on tree-lined streets are 3-15% more valuable, and homes near a large park or open space are 8-20% more valuable. We all want to live in an aesthetically beautiful area and that means adding more nature. Trees make spaces feel calm, cool pavement by 2-4 degrees Celsius, buffer noise and sound pollution, and provide spaces for recreation.

Add a forest anywhere and it will feel like paradise.

Biodiversity is crucial to keeping those wild spaces alive. In the mid 18th and 19th centuries, one James Hillhouse planted hundreds of Elm trees throughout his town of New Haven, Connecticut. It was dubbed the “City of Elms,” and sparked “Elm Streets” across the American East. Tree-lined streets became the desired aesthetic until, in the 20th century, one fungus brought over from Europe spread Dutch Elm Disease across the country. Urban forestry projects were killed off in a manner of decades, cities lost their beauty and appeal, and scientists began to call for diversification among species.

In the 1990s, the forest geneticist Frank Santamour coined the 10-20-30 rule to avoid another elm-like apocalypse: Urban forests should contain no more than 10% of any one species, 20% of any one genus, and 30% of any one family. But urban forestry departments still prioritize human comfort over any other species, and only diversify for matters of survival.

What if we diversified for the sake of other species too?

Ginsberg has turned to individuals as the answer. Upset with the lack of political and technological will, like Volataire’s Candide, she looks at the loss of the natural world and says, “at least I can plant a garden.”

As an extension of her Pollinator Pathmaker project, she created a garden in her own backyard, not for herself but for insects. Then she taught others how to do the same. Her website Pollinator.Art, allows citizens to input their location, garden size, soil type, and sun access; choose the type and variety of pollinators they want to attract; and generate a garden plot along with instructions on how to plant it. It’s only available to European residents at the moment, but she plans to scale it to other locations soon.

“We are undertaking a major research project with Exeter University and Edinburgh University, where we've planted 17 DIY artworks in a village in Cornwall,” she says. “Seventeen groups of residents have given up a bit of their gardens, and then we have 15 control gardens, and we're studying the network between all the artworks, both on an insect level and a human level… Those pilot studies show really great results. Doing a proper study might actually show us that this is a good way of supporting insect diversity.”

If everyone removed their lawns and built gardens for insects, she reasons, we could create space for so many more ecosystems to thrive. “Lawns are very much the encapsulation of the way we treat nature,” Ginsberg says. “It's about our dominion over nature, controlling it and achieving perfect uniformity to create a sort of outdoor carpet for humans to stand on, and covering it with chemicals, rather than seeing it as a place that's supporting us in a more dynamic and intrinsic way.”

I value human flourishing above all else, but I also see an abundant natural world as an essential part of that flourishing. Studying the work of Ginsberg and Ritchie gave me tangible ways to work toward that. In a world where politicians are doing so little to protect biodiversity, and our technological advances are coming up short, I can at least grow my own garden. I can easily remove beef and lamb products from my diet and plant a garden of wildflowers in my yard for insects, creating more space in the world for plants and animals to thrive.

I can play a role in creating the interspecies future I want to live in. Not just for the sake of other species, but for my own enjoyment as well.

“It’s some mad, mad venture,” Ginsberg says of her work, “but I just want people to plant art.”

I hope we all do.

Thank you all for reading and collecting this series, and I appreciate your patience as I finished it! This essay was meant to publish last week, but I was able to schedule an interview with Alexandra Daisy Ginsberg at the last minute and moved the article back a week to accommodate her. I’m glad I did.

You can still collect the TERRAFORM series as a digital or print pamphlet here.

Thanks for reading!

It delights me to read stuff like this and to see that there are people really thinking about what an alternative, hopeful future looks like. I appreciate you sharing this, and look forward to reading more of your articles!

It's a great point about tunnel vision on the Panda at the expense of the unplushiable. I tend to look at conservation efforts through the lens of possibility, with the knowledge that some possibilities are more desirable than others.

Life builds on a platform of energy and material to create a magnificent world above and we can support it by protecting ecosystems at all scales. For the wild it's about discovering those critical cycles that can't easily adapt or restart. For humans, it is our social ecosystems that seem to need the most effort.