My sister spent the past year living in Maui, and I got to spend five weeks staying with her. We had so much fun exploring the island, and even attending a surf camp together, but one of my favorite parts about my travels was learning more about native Hawaiian history and culture. It made me wonder what Maui might have looked like today if it had stayed Mauian. This is also my entry for my ecotopia writing prompt!

It was my first day at Maui University, but as I wound through the treetops, wandering the interconnected treehouses that made up the campus, it wasn’t a classroom I was looking for, but a home.

The Iao valley was steeped in mist, the sun shining through the droplets and scattering rainbows in the air. The professors lived on campus, as did the students, and I was looking for my doctoral advisor who would be hosting me for the semester.

I wandered dorms built into the cliffs, and students eating fresh fish on terraces in the clouds. Finally, a knot in a giant tree denoted the small hut on the edge of town. A small unassuming woman opened the door, her lined eyes smiling, her white hair swept into a bun.

“Welcome to Maui,” she said with a hug.

I was here to study ecology and Maui was one of the most interesting examples in the world. When the island became a US state more than 200 years ago, it was on the condition that it retain its reverence to the earth. Land was not meant to be owned by humans, Maui leaders said, but shared.

That always struck me. I had pursued my graduate and then doctoral studies in California, where the land had long ago been purchased up—turned into second homes and vacation rentals, giant mansions towering over the beaches. Purchasing wasn’t an option, even renting was unaffordable. I wound up getting a small sailboat and living off the coast.

It was there that I met Manu. One day I was paddling into a wave when it raised 40 feet into the air. I didn’t have time to prepare as I was plunged into the depths of the sea. I spiraled into the ocean, the darkness overcame me, my air ran out. I thought I would be lost to the sea until I awoke on the shore and he was standing over me, a fishhook dangling from his neck.

I shook myself of the memory. “Thank you so much for hosting me,” I said.

“Welcome to my ‘Ohana!” she returned.

My advisor was a sentient, an AI elder and keeper of the lands of Maui. She had been programmed with vast ecological data and was tasked at keeping the land and ocean wild and thriving, and for the best benefit of those who lived within its ecosystem. Hers was a constant balance between the needs of humans and the wilds that helped them thrive.

I had already studied the literature, the Hawaiian government owned the island and they built two ecovillages in the mountains, one in the Iao valley, where the university was, and the other on the Haleakala mountain. In the middle stretched wide glass greenhouses, with the coasts protected as open space for all to explore.

Residents could rent, not own, in either community with up to 50-year leases. There were no cars on the island, just an electric sky train that connected the two villages and ebike trails that circled the coasts. Later I would borrow a bike and head to the surf—huts scattered at every beach had surfboards for anyone to use.

But there was also a more personal reason I was here.

“Do you recognize this?” I asked, pulling the makau from my pocket.

The small bone fishhook hung from a golden chain. Manu visited my boat every day after we met. He had been spearfishing the day of the tsunami, he said, and he had ducked beneath the waves to save me before I even saw it coming. But then he joined me for dinner, then he returned night-after-night, then he looked at me with those golden eyes.

I spent the summer in his arms, until he disappeared.

My advisor held the makau in her hand, her eyes glistening with memory. “Yes, and I know who it belongs to.” She looked at me knowingly.

We walked into her hut where glass walls overlooked the entire campus, a waterfall poured behind us and beneath our feet as we looked out on the sparkling city. I should have been excited about the lush wildlife that had been allowed to thrive, the coral reef that still bloomed around the shores—other parts of the world had much to learn from this experiment in land ownership.

But my mind was on my advisor as she poured a pot of tea, some tropical flower blooming in my cup.

“Go on,” my advisor said as she settled into her chair. “Ask me what you came to ask me.”

“Manu,” I said as I sat beside her. “Is he….”

“Manu was the keeper of the seas. As much as I know about ecology, he knew about the ocean,” she said. “We worked together for many years, ensuring that the ecosystems of Maui, and eventually all of the Hawaiian Islands were allowed to thrive. It was he who researched all the wisdom we needed to ensure the health of our coral reefs.”

She was speaking in the past tense, my breath fell uneven.

“Was?” I asked shakily.

“Manu died more than 100 years ago,” she said. “I’m afraid you must have met his sentient.”

Author’s Commentary

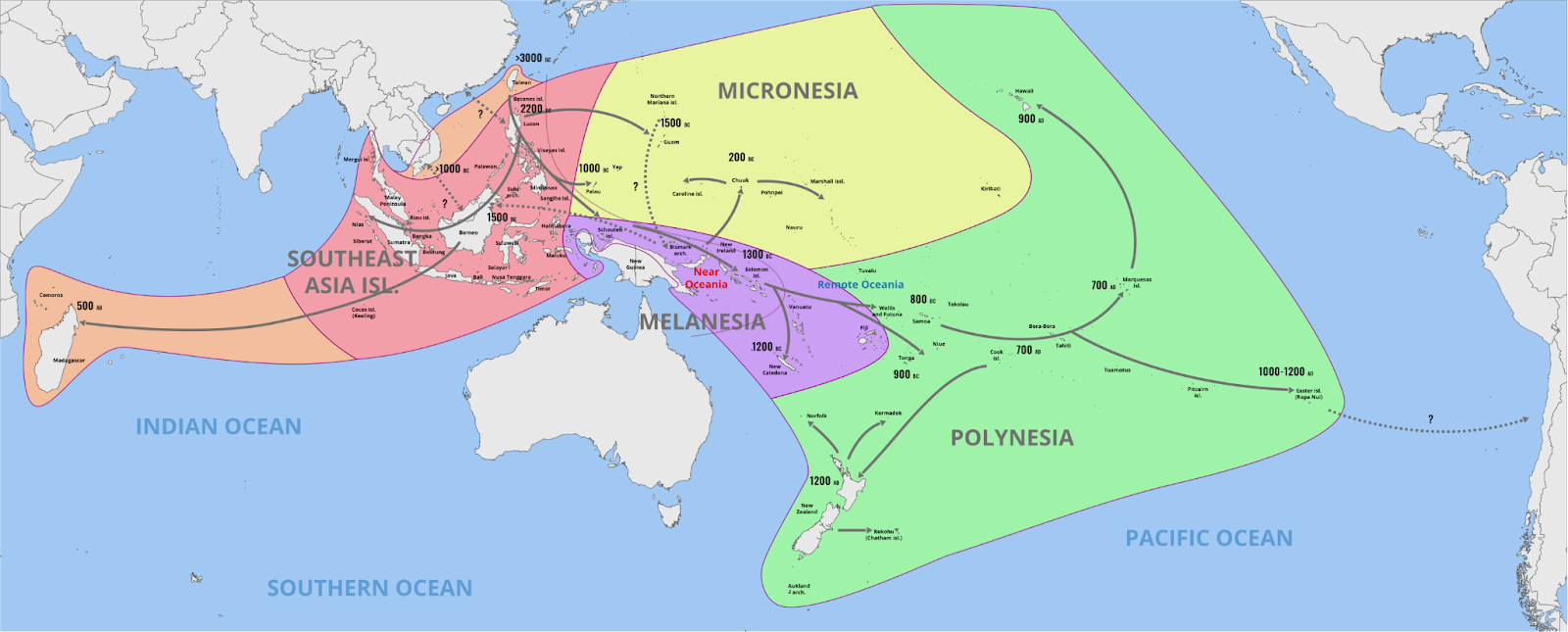

The Hawaiian islands (and many others) were first settled by seafaring voyagers from the eastern Polynesian islands between 900 and 1200 CE.

By the 15th century, the islands (Hawaiʻi, Kauaʻi, Lānaʻi, Maui, Molokaʻi, Niʻihau, and Oʻahu) were each ruled by a high chief, and each island was further subdivided into ahupua’a, local communities which were each ruled by their own local chief.

The ahupua’a were divided like a pie with the volcano at their center. Each community got a slice of land stretching from the top of a mountain at one end down to the ocean at the other. This meant each community had a complete ecosystem including water from the mountains, wood for building, fertile land for farming, and ocean for fishing.

Here’s a map of Maui’s ahupua’a. The island has two volcanoes. You can see how those formed the center of the pie, with each ahupua’a making up one slice of it.

Because of this structure, each ahupua’a community was self-sustaining. Though the land was divided, it was not owned. It was believed that the land belonged to the gods and that the humans were just managers of the land. In this way, each ahupua’a belonged to a community and was administered by its konohiki, who placed restrictions on fishing during certain seasons and planting in certain locations to make sure the land could adequately provide for everyone.

People worked the land as farmers and fishermen, they wove baskets and practiced martial arts, they provided everything their community needed as dictated by their chief and Konohiki. Overtime, some land might become crowded or depleted as new family members were added. That’s why, whenever a chief died, the land was reallocated to make sure everyone had access to water and resources.

Is any of this starting to sound familiar? Ancient Hawaii (circa the 15th century) is nearly identical to the island of Utopia as laid out by Thomas More (circa the 16th century)!

Like More’s Utopia, ancient Hawaii wasn’t utopian by today’s standards. There was a caste system and thus a hierarchy of people who were treated better or worse depending on the families they were born into (More’s utopia also had a slave class that natives were lumped into). There were also strict rules called kapu that forbade women from eating with men as well as from eating many of the abundant foods on the islands like coconuts, bananas, and many kinds of fish. Breaking these, and any other rules, was punishable by death.

But I was intrigued by the idea of communal property and a local community leader who manages the land, and I was even more curious how that might have evolved if Maui had stayed Mauian to this day. And specifically, if it weren’t for the two events that changed everything: if King Kamehameha hadn’t conquered all of the Hawaiian islands, creating Hawaii and making himself king over all of them; and if his son King Kamehameha III hadn’t introduced the Māhele—which introduced land ownership and made it available for foreign purchase.

The most exciting part of this story was that all of the research for it came to me through oral history: I learned about the ahupua’a system from Carole Berthiaume, one of our counselors at Maui Surfer Girls. I learned about a similar method employed in the Cook Islands called Tapere, after a discussion with a fellow camper from the Cook Islands. I learned more about the mythologies of Hawaii from our hula instructor Nalani.

Then I followed this up with some research into Hawaiian mythology, where I stumbled upon the story of Pele, the goddess who fell in love with a man that turned out to be a ghost. I wanted to imagine a modern version of that story, and that’s how this turned out to be a ghost story, but with AI.

This is a beautiful story, Elle! The best you wrote so far and I can see it turning into a whole novel. Your utopian novel. 😁

I love that you wrote a story for your own writing prompt! 😄

So glad that you picked up on the ancient practice of not owning and exploring the lands but being its stewards, taking from nature only as much as we need, maintaining it for generations to come. Our world would indeed be a different place if we would’ve kept that worldview.

I really enjoy your story and the short summary of Hawaii’s history. Well done 👍

Love this and it raises an important question—can we ever have utopia when people will never stop wanting giant beach houses.

Just look at Obama’s house on Maui, it’s really all one needs to see to lose faith...