What if its not cool to be a bad capitalist anymore?

Then will companies behave better?

If my last essay asked how we could incentivize companies to be better, the prevailing response from capitalists is that we shouldn’t.

“I don't believe government regulation solves these problems,” Davis Smith, founder of Cotopaxi tells me. “I think there's a role for it, especially in terms of protecting the earth—and that oftentimes is going to come from regulation—but in terms of businesses I think what we really need is a society that expects more out of businesses.”

This is a common refrain in business. Let the market regulate us. Let society regulate us. Get the government involved only if it’s absolutely necessary.

“The market demand will push us in the right direction, versus regulating it,” Smith says. “When we create a world where the best businesses are the most profitable, profitable businesses are the ones that are actually doing things right that people want to support and the ones that are the most destructive are really suffering. I believe you will have a better business and more profitable business by doing things the right way. And that wasn't always the case, but I think it is today.”

In other words: We won’t work for companies that suck and we won’t buy from companies that suck, therefore companies that suck will have to get better or risk going out of business. It’s just not cool to be the rich capitalist driving a gas-guzzling Ferrari, with a company that pollutes the environment and employees who are overworked and underpaid anymore. Much better to be the Tesla-driving CEO on a mission to end poverty, who takes a pay cut so he can keep his employees during the pandemic even as he donates millions to charity each year.

“Twenty years ago, when I was in business school, we were celebrating Jack Welch as the CEO of the century, and he laid off 100,000 people and was ruthless and that was celebrated,” Smith says. “That wouldn't be celebrated today.”

There’s certainly something to that. Throughout history, we have witnessed a continual outmoding of our worser behaviors. During the French Revolution, it just wasn’t a good look to sit around in a frilly frock eating caviar anymore—not when their workers couldn’t afford bread! Doing so could lose a gentleman his head!

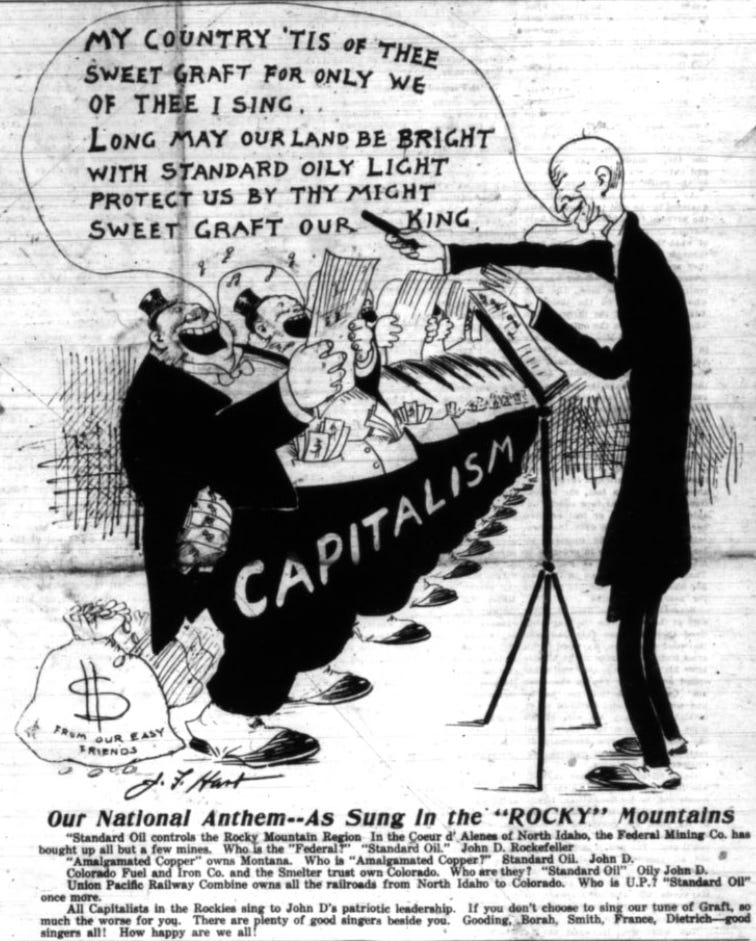

During the Gilded Age, communist sentiment threatened to upend the livelihoods of American industrialists. At the time, John D. Rockefeller was getting wealthy on oil and Andrew Carnegie was getting wealthy on steel and both stood to lose all of it if they didn’t treat their workers better. An 1892 labor strike at Carnegie’s Pennsylvania steel plant turned bloody when the workers union asked for a wage increase and the company countered with a wage decrease—an anarchist even shot at Carnegie’s partner. Then, a 1913 labor strike at one of Rockefeller’s Colorado mines forced striking miners to abdicate their homes and live in tent cities erected by the union.

Public opinion turned against Carnegie and Rockefeller with the latter dragged into several public hearings against him. And maybe that’s what inspired both to become philanthropists. In 1889, Carnegie wrote an essay called “The Gospel of Wealth,” detailing how the wealthy should use their money for the greater good. “This, then, is held to be the duty of the man of wealth,” he wrote, “To set an example of modest, unostentatious living, shunning display or extravagance; to provide moderately for the legitimate wants of those dependent upon him, to consider all surplus revenues which come to him simply as trust funds, which he is called upon to administer… to produce the most beneficial results for the community.”

The quest to be the better billionaire continues to drive the behavior of modern capitalists. After all, it wasn’t a minimum wage increase that forced Jeff Bezos to pay Amazon employees better, it was bad press. Turns out it’s not a good look to buy yourself a multi-million-dollar yacht and race other billionaires to space when your employees are paid minimum wage and peeing in bottles. Especially when your peers include the philanthropic Bill Gates on a mission to end poverty and your ex-wife donates $14 billion after your divorce. Maybe that’s why, in 2022, Bezos raised the minimum wage of Amazon employees to $19, the same year he announced he would give away most of his fortune in his lifetime.

The same motivation caused Facebook founder Mark Zuckerberg to lament the lack of press coverage for his philanthropic endeavors. “Why don’t people think of me the same way as Bill Gates?” he once asked his advisors.

Maybe that’s why so many business owners opt to control the narrative by purchasing media companies. Jeff Bezos owns The Washington Post, Marc Benioff owns Time, Elon Musk owns Twitter. The media, and especially social media, have become powerful enforcers of our better behaviors. The “climate criminals” movement, for one, made private jet use uncouth. And companies have gone downhill for failing societal convention. Think about The Ringling Bros. and Barnum & Bailey Circus, which was put out of business by animal rights activists. Or Victoria’s Secret, which came under fire when a TikTok singer called the company out as misogynist, and not for the first time. The lingerie company previously retired its annual fashion show and swimsuit lines due to changing views on gender and body image. Or what about Mattel, which has consistently reinvented Barbie to avoid cancellation?

We wouldn’t tolerate the societal, working, or environmental conditions of 19th or 20th centuries companies today. And people living 100 years from now probably wouldn’t tolerate the societal, working, or environmental conditions of companies today. Smith thinks this is a force so strong it might one day put him out of business. “We look back now and we're like, ‘oh my gosh, the way that we saw race, the way that we saw gender, these things were so backward and wrong,” he says. “If I look forward 100 years, I think ‘what are the things that they're going to look back at us and criticize?’ I think it's going to be around consumption and the way that we've overconsumed and destroyed the planet.”

This is especially concerning to Smith—Cotopaxi sells outdoor clothing and gear. “Ninety-seven percent of our product last year was made of remnant recycled and responsibly made materials and it's going to be 100% by 2025. So I'm really proud of how we're doing it,” Smith says. “At the same time, are we having a negative impact on the planet? We are. I can't pretend that we're not. We're creating a product that gets used and then eventually discarded. It has a negative impact on the planet. Whenever the useful life of that product is over, it's going to go to a landfill anyway, and it's made of polyester—it's petroleum based.”

Smith is very aware that Cotopaxi, and many retail businesses like his, could fall out of fashion as public opinion sways away from consumerism. “I hope that my great great grandchildren don't look at me and say, ‘Wow, what a loser. Davis Smith didn't do a good enough job protecting our planet.’ That’s something I think about every day,” he says.

In his book Tomorrow’s Capitalist, Alan Murray thinks this will force companies to adopt business practices that are for the greater good. Because if they don’t, they won’t be successful. “You can’t have a successful company in the long term if your employees can’t make a decent living; you can’t have a successful company if social turmoil is undermining the community, the society, or the political context you must operate in; you can’t have a successful company if the climate is creating chaos.”

“This is the beauty of capitalism,” Smith echoes. “There will be entrepreneurs that will see opportunities to go do something better and they will steal market share and they will win.”

If I agree that public opinion can be a powerful motivator, I’m not convinced it makes a good enforcer. We may not be shooting at company founders anymore, and we haven’t seen unions erecting tents to house striking workers in a while, but the recent Insider strike felt familiar to the ones against Rockefeller and Carnegie more than 100 years ago. The Washington Post called out “the company’s millionaire founder” who had to write his own articles during the strike and a “deep-pocketed editor in chief was caught on video tearing down fliers bearing his face with the phrase, ‘Have you seen this millionaire?’”

The strike was one of many writer’s strikes that played out over the past few weeks, pitting the immense wealth at the top of our media conglomerates, publishing houses, and Hollywood Studios, against those who write all of our news, journalism, books, shows, and movies. The Insider strike ended with only the mildest gains at the bottom. The new deal raises the minimum salary for Insider staffers from $60,000 to $65,000 a year, “includes a pledge to not lay off any more employees for the rest of the year, and offers an immediate 3.5 percent raise for most staff once the contract is ratified.”

That society demands better does make society better. And Smith is part of a growing movement of capitalists who are figuring out how to use their profits, not just for the shareholders at the top, but for the greater good. He is joined by Yvon Chouinard, the founder of Patagonia, whose company is now owned by a trust that donates its profits to environmental initiatives. As he puts it, “Earth is now our only shareholder.” I’m grateful these companies exist as alternative directives for capitalism, but I also hope we don’t have to depend on the benevolence of capitalists to scale them. After all, there might be those who buy Cotopaxi or Patagonia clothing because it seems like the ethical thing to do. But there are many more buying from H&M because it’s cheap. Cotopaxi made more than $100 million in revenue in 2022 and Patagonia made more than $1 billion, but H&M made more than $22 billion, and this is a company that was faking their “green scores.”

“We're all hypocrites,” Smith says. “We all want nice things and we want to replace old things with new things and nicer things. And as a business, you want to grow and have an opportunity to make a mark so you're going to do that by growing. So yeah, I don't know the answer.”

Public opinion certainly plays a role—the fact that H&M even came out with green scores is proof enough of Patagonia and Cotopaxi’s influence on the market—but even Rockefeller and Carnegie weren’t mitigated by the market alone. In 1890, the United States introduced The Sherman Antitrust Act to outlaw monopolies and, more specifically, break up Standard Oil. What may have begun as a movement, a rallying cry against those at the top, was eventually enforced by the government for the betterment of those at the bottom.

And maybe that’s where government regulation could play a role today. Even if Smith is hesitant. “That's more of the communist or socialist perspective, which is ‘let's have the government regulate and enforce the way that we think it should be done.’ And I don't think that's the right way,” Smith says. “But there is a place for government and there's a there is a place for regulation. And we do need some of that.”

If there is a balance between market and government regulation, I plan to explore that in my next essays. In the meantime, I’d love to know your thoughts! Join the discussion in our literary salon 👇🏻

Thanks for reading,

Marginalia

Here are some notes from the margins of my research.