Who should control AI?

Nonprofits aren't our only option.

This essay is research for a book I’m writing called We Should Own The Economy, readers can invest in the project and earn a share of profits when it’s done 👇🏻

When OpenAI launched in 2015, they did so with an impressive mission: To develop AI that would benefit humanity by automating repetitive work or curing cancer, but without unintended consequences that might harm humanity, like rapidly displacing jobs or trying to kill us all.

At the time, Google was already working on AI technology and Sam Altman, Greg Brockman, and Elon Musk thought that wasn’t a good idea. Altman wrote: “[I’ve] been thinking a lot about whether it’s possible to stop humanity from developing AI. I think the answer is almost definitely not. If it’s going to happen anyway, it seems like it would be good for someone other than Google to do it first.”

The three launched a nonprofit organization and research lab with no equity shareholders, just donations from tech philanthropists. They hoped to raise $1 billion in donation commitments so they could develop the technology without taking on investors. “Our goal is to advance digital intelligence in the way that is most likely to benefit humanity as a whole, unconstrained by a need to generate financial return,” they said at the time. “Since our research is free from financial obligations, we can better focus on a positive human impact.”

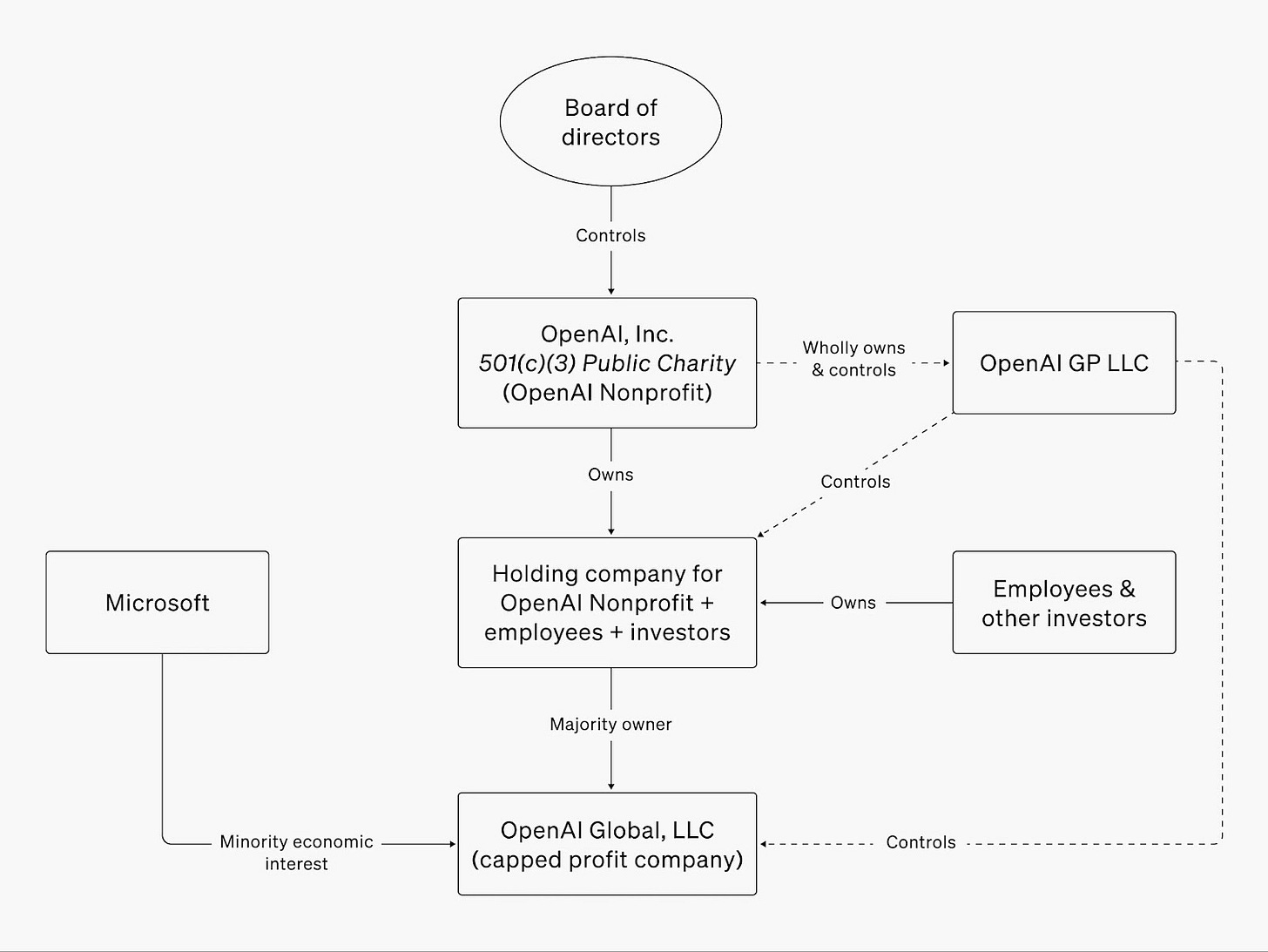

Three years later, competitors from Google, Amazon, and Meta had significantly ramped up and OpenAI had raised only $137 million. The company needed more money to fund R&D and computing costs, but they still wanted to do it safely. In 2019 they restructured, creating a for-profit company that could attract investment as well as give employees shares in its success, but with earnings capped at 100x their investment. Anything above that funded the nonprofit, which served as the company’s owner and controlling entity while remaining beholden to their ethical mission, not investors.

This new hybrid structure was an innovative approach to ethical technology ownership. But there was inherent friction between the two organizations from the start. The nonprofit wasn’t building the technology—the for-profit was—and there was limited oversight the nonprofit could provide without being involved in day-to-day operations.

The two organizations also had competing values. Until 2019, the nonprofit had been open source, publishing their research and sharing code freely. Now, technical details for GPT-3 and GPT-4 were withheld on competitive grounds. If Google copied OpenAI’s code and beat them to the market, they would create the very circumstances OpenAI was funded to avoid: Google rushing the technology to market to benefit shareholders, rather than OpenAI developing it safely for the benefit of humanity.

After OpenAI debuted their first product, ChatGPT, in 2022, the friction intensified. The nonprofit worried the company was growing too fast—that the model still incentivized risky, profit-driven deployment of AI until the cap kicked in. Everything came to a head in November of 2023 when the nonprofit board abruptly fired OpenAI CEO Sam Altman and asked co-founder and President Greg Brockman to step down as co-chair, citing lack of transparency and safety concerns.

Immediately, the board faced massive backlash from the company—employees universally backed Altman, as did investors. Within a matter of days, Microsoft announced they would hire Altman and Brockman to lead a new AI team at Microsoft. Shortly after, nearly all of OpenAI’s employees—over 700 staff members—signed an open letter to the board demanding the reinstatement of Altman and the resignation of the board members who had fired him. They accused the board of abuse, saying: “Your conduct has made it clear you did not have the competence to oversee OpenAI.”

If the board didn’t comply, employees threatened to quit en masse and follow Altman to Microsoft.

Less than a week after the firing, Altman and Brockman were reinstated and the entire board was replaced. A law firm investigating the issue found the nonprofit’s reasons for firing lacking, and found no ethical or safety breaches on the part of Altman. One of the board members responsible for the firing even acknowledged their error and publicly denounced their prior decision. The company returned to business as usual, but began exploring alternative governance structures that might work better than their current one.

By the end of 2024, OpenAI announced their new structure: The nonprofit would be removed as the owner and controller of the company and instead become a benefactor of it, owning shares in the company which would fund their social mission. Meanwhile, the for-profit company would become a Public Benefit Corporation, just like competitors Anthropic and xAI.

Critics panned the move as a bad one. Public Benefit Corporations do not enforce the better actions of companies, and fail to hold them accountable for social results. More critically: Without the nonprofit holding the company accountable, it could now answer to corporate interests instead—like SoftBank, now leading a $40 billion funding round. As a for-profit company, the board could comprise the very financial interests the organization once found dangerous.

In April of 2025, a group of former OpenAI and Google DeepMind employees, as well as nonprofit organizations and law firms, penned an open letter to the California and Delaware Attorneys General arguing against the move, and demanding the nonprofit remain in control of the company.

It worked.

On May 5th, OpenAI announced that, after discussions with both Attorneys General and other civic groups, they would leave the nonprofit in place as the company’s controlling entity. The for-profit business would still become a Public Benefit Company, and the nonprofit organization would still benefit from that company as a primary shareholder. The cap on investor returns was removed and OpenAI can now raise significant investment, but the nonprofit retains the power to fire the CEO if the organization acts unethically in the future.

I think this is an interesting compromise, and perhaps a good one. Several companies have nonprofit-controlled boards including Novo Nordisk, Bosch, and the Guardian; and many are doing interesting things with Public Benefit Corporations, like Patagonia. But dozens of AI competitors have since entered the market, none of them particularly ethically controlled. Anthropic is controlled by investors and founders, DeepMind by Google. Chinese competitors have entered the space, forcing every organization to act more quickly. Despite OpenAI’s ethical intentions, investment-backed AI is here, with shareholders racing products to market. It simply won’t matter if OpenAI develops “safe AI,” if the rest of the world develops “unsafe AI.”

It’s worth asking who should control these companies. A nonprofit might work in OpenAI’s case, but what about the rest of them?

We are demanding better ownership structures for risky technologies, and for companies at large, and OpenAI has brought that to the forefront. But let’s remember what specifically this debate is about: We are asking who should serve on the board of directors for a company. We are asking who should be part of that inner circle that has the power to fire the CEO when they act unethically. Investors will prioritize financial growth above all other objectives, but nonprofits don’t always prioritize the business and can risk its existence altogether.

Thankfully, our options are not split between a board controlled by investors and a board controlled by a nonprofit.

There is a third, and potentially better option available to us: A board controlled by employees.

Far more than any other entity, it has been employees who have held OpenAI accountable. In 2019, employees overwhelmingly sided with Altman, calling the nonprofit incapable of making safety calls. Today, employees have largely sided with the nonprofit, with prominent AI researchers leaving the company due to safety concerns, and joining the open letter or participating in lawsuits against the organization.

For every claim that a nonprofit entity will best hold the AI company responsible for its actions, employees have overwhelmingly done it better. That makes sense: No one understands the ethical ramifications of the technology they are building better than the employees who are actually building it. They have intimate knowledge on whether the company is acting in humanity’s best interest, and are the first to serve as its whistleblowers when it isn’t.

It was an employee who spoke out against Meta when it knowingly caused harm to adolescents and prioritized engagement over safety.

It was an employee who spoke out against Cambridge Analytica for harvesting personal Facebook data to influence political elections.

It was employees who spoke out against Theranos when it made fraudulent claims about its blood-testing technology.

It was employees who spoke out about accounting irregularities at Enron, widespread fraud at WorldCom, and broken intelligence communications at the FBI leading up to 9/11.

If we want our companies to be held accountable for their actions and to act in the best interest of humanity, who better to enforce that than employees?

That’s what Jason Kelly thought. As the founder and CEO of Ginkgo Bioworks, he had similar fears about putting synthetic biology in the wrong hands.

“We're literally engineering life, and that is incredible if it goes well, but it is also a powerful technology with the capacity for both extreme good and extreme bad,” Daniel Marshall, ownership and communications manager at Ginkgo, told me. “A lot of the ways people talk about AI right now are how we were thinking about our technology back then. We need to make sure this technology is ultimately in the hands of people, not exclusively controlled by arm’s length capital with the sole focus of ROI.”

The company saw an answer in the dual class shares popularized by tech companies. Traditionally, investors held board seats to ensure their investments maximize their returns, but the Googles and Facebooks didn’t like that. As Kelly explains it: “The board hires and fires the CEO, so the CEO really cares who's on the board. What does Zuckerberg do? He creates two classes of shares, one for Fidelity and one for Mark Zuckerberg.”

When Facebook went public, investors received Class A shares which entitled them to one vote each, but founders received Class B shares which entitled them to 10 votes each. So long as founders owned more than 9.1% of the company, they controlled the majority of the board vote, not investors. Investors might own more of the company and participate in more of the company’s earnings, but founders owned more of the vote, and control over the company. This allowed tech companies to fund R&D projects without immediate returns—like self-driving cars and AI—and has since become a default option for many founding teams.

There are obvious risks to this model—namely that no one can disagree with the CEO on ethical issues. Kelly thought we could fix that problem by expanding super voting shares to all employees.”

“Facebook is a worker-controlled C Corp,” Kelly explained, “with the asterisk that the worker is Mark Zuckerberg.”

If super voting shares were expanded to all workers, then employees would control the board—not just Zuckerberg, and not just investors. So long as they own more than 9.1% of corporate equity, they control the majority of voting power. When Ginkgo went public in 2021, that’s just what they did. Employees start out with Class A shares but have the opportunity to convert them to Class B once a year. If they leave the company or sell their shares on the stock market, they convert back to Class A, ensuring voting power remains concentrated with current employees.

Today, Ginkgo’s founders own most of the employee equity, and thus retain more voting power over the board, but employees earn more equity each year. As founders eventually retire, their shares will revert to Class A, keeping supervoting power solely in the hands of current employees. Employees control the company, and will continue to control it over time.

“What we mean by ‘control the company’ is they will have the ability to elect the board,” Kelly reiterates. “Employees won’t do workplace direct democracy and vote on their salaries or anything like that. We’re keeping the C Corp structure with the CEO as the chosen representative of the board to lead the company because this has been proven to be the most competitive management structure in the market. But that CEO can be fired by the board, and in the case of a worker-controlled company the board is elected by employees.”

This is a powerful check on the company, and a much better one than investors or founders.

“The problem with having one human [in control]—well look at Elon,” Kelly says. But if employees control the board, there’s a level of accountability. “If the CEO starts going off the rails morally, employees are going to change the board and get them fired. The CEO knows this, and that affects how they act.”

“Our thesis that workers care how the platform is used has been borne out tremendously,” Marshall says. “There have been vigorous and sophisticated debates about different programs we've had and their potential impacts on the world. Caring was sort of the raison d'etre of the Class B super voting shares so that even when the founders leave, employees would help steward the platform in perpetuity. And ultimately, we also believe this model is best for the creation of long-term shareholder value for all shareholders.”

Two other companies have used dual class structures this way: UPS and SAIC. UPS was already employee-owned before their IPO and preserved that structure when they went public in 1999. Incredibly, 90% of corporate stock was owned by former and current employees back then (with 10x voting rights), and only 10% was publicly held (with 1x voting rights). Over the years, employees gradually sold their shares, and today about 15% of shares are held by UPS employees, with the other 85% held by public shareholders. Despite owning a minority of shares, with 10x the voting rights, employees still control 64% of the votes and have controlled the board for 25 years. Investors have tried to get rid of supervoting shares many times, but employees voted them down every time, ensuring the company remained in employee interests.

This structure could be beneficial to tech companies too, and that’s the bet Ginkgo is making.

“Look, we’re trying to make a platform that makes genetic engineering easy, and if it works at scale it’s going to be a pretty big deal. It could be very powerful, but also potentially dangerous,” Kelly says. “Who should control that? We think it should be workers.”

Workers at OpenAI, as well as Anthropic and DeepMind, have been some of the most vocal proponents of developing AI ethically—why not let them control the board too? They wouldn’t have to leave the company or write open letters to get the CEO’s attention, but could hire a new board if the company starts to act against our best interests, and even fire the CEO if things get dire. This, I think, would place an important check on our companies and ensure the ethical development of technology, not just at OpenAI, but at all of the organizations building our future.

But I’d love to know what you think 👇🏻

Thanks for reading,

P.S. This chapter has been added to my living manuscript which you can read and comment on here. Can you believe the book is already at 20,000 words??

P.P.S. Thank you Daniel Marshall, Jason Kelly, Joseph Fridman, and the Ginkgo Bioworks team for your help researching this article. And thank you Shoni for the quick edits!

P.P.S. Mandatory Disclosure regarding that link at the top: The Elysian is "testing the waters" to gauge investor interest in an offering under Regulation Crowdfunding. No money or other consideration is being solicited. If sent, it will not be accepted. No offer to buy securities will be accepted. No part of the purchase price will be received until a Form C is filed and only through Wefunder’s platform. Any indication of interest involves no obligation or commitment of any kind.

Further reading:

Here are a few notes from the margins of my research: