Every company should be owned by its employees

Central States Manufacturing as a model for exiting to employee-ownership.

There are 47 millionaires working for Central States Manufacturing and they’re not all in the C-Suite. Many of them are drivers or machinists—blue-collar workers for the company.

How? The company is owned by its employees. Every worker gets a salary but also a percentage of their salary in stock ownership. When the company does well so do the employees—all of them, not just the ones at the top.

And the company is doing well. “When we sat down eight years ago, we said we want to be a billion-dollar company and have 1,500 people, we are on track to be both of those this year,” Tim Ruger, president of Central States, tells me.

That’s right, this manufacturing company will become one of only 6,000 companies earning more than $1 billion in revenue. But unlike Walmart, Amazon, and Apple, it’s not just the executives getting paid out.

“It’s not like 80 percent of the company is owned by management and the rest is owned by employees, it’s really well spread across all functions,” Ruger tells me. “We've got a number of people that have been here 15, 20 years and they have $1 million plus balances, which is really cool for a person that came out of high school and runs our rollformer. You can’t do that everywhere.”

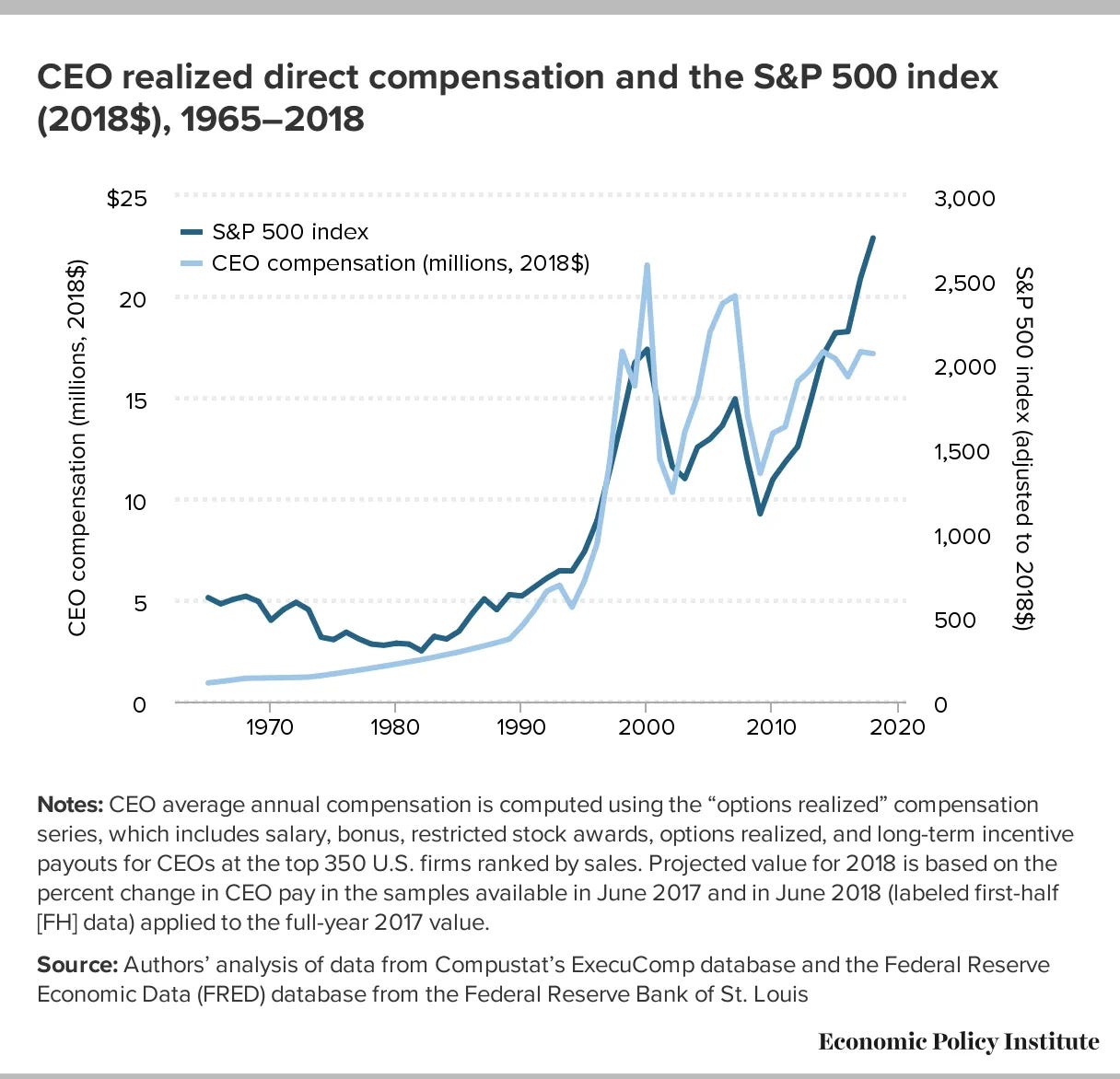

He’s right, and because you can’t do that everywhere there is a huge wealth disparity in America. Even though the economy has been on an upward trajectory for a century, the wealth it generates has funneled to a much smaller population who owns it. After a 1990s bill meant executives started getting paid in stock options while the rest of their employees earned a static salary executive pay skyrocketed with the market while their workers’ pay stagnated.

If employees had also owned part of the company their pay would have skyrocketed with the market too, but they didn’t. “It's hard to build true wealth for yourself if you don't have some type of ownership in something, and it's hard for most people to get ownership in something,” Ruger says.

Upping the minimum wage won’t fix that. As Nathan Schneider says in his book Everything for Everyone: “One way or another, wealth is going to the owners—of where we live, where we work, and what we consume.”

So why not make workers the owners?

There is a growing movement to do just that. Central States is one of 6,533 companies that have formed an Employee Stock Ownership Plan (or ESOP) in the United States, and that number is growing by about 250 companies annually. That’s 14.7 million employees who have ownership in companies worth, collectively, $2.1 trillion.

Every year, those employees get a percentage of their salaries in company stock. During Central States’ worst year, employees earned the equivalent of 6 percent of their pay in stock, during their best they earned 26 percent. Last year, an employee earning $100,000 a year received $26,000 worth of stock in their account. As the company has grown the value of that stock has averaged 20 percent returns annually, outperforming the stock market.

These stock accounts are in addition to traditional retirement accounts, not instead of them. Noelle Montaño, executive director for ESCA, tells me 90 percent of employees with an ESOP account also have a 401k or other retirement account, which means employees earn upside without any downside. Employees without an ESOP don’t have that kind of advantage—50 percent don’t have a retirement account at all.

Just like Jeff Bezos can sell a portion of his Amazon stock to buy a new house, employees at ESOPs can pull money out of those stock accounts to pay for tuition, medical bills, or as a downpayment on a primary residence.

“We have several in production and drivers who have been here for over 20 years that have multi-million dollar accounts,” Chad Ware, Central States’ CFO tells me. “We’ve had several folks take out enough money to buy a home outright.”

An ESOP account functions a lot like a second 401k, but invested solely in the company. Employees can pull out whenever they’d like, but outside of those approved uses they will have to pay taxes and an early withdrawal fee to remove the funds before the age of 59 ½. After they leave the company or retire, the complete balance of their accounts will be paid out to them over a six-year period.

This means the company needs to have that cash on hand to pay out, and this has to be budgeted into their annual cash flow. But it also means the employees are incentivized to participate in the wellbeing of the company.

On the stock market, executives are expected to produce quarterly results, often to the detriment of their companies’ long-term success. After Boeing famously rushed the rollout of its 737 MAX aircraft to meet quarterly expectations, fatal crashes and safety concerns killed 346 people and cost the company $20 billion. Companies like Wells Fargo, Sears, and Bausch Health have similarly cut corners to inflate short-term results at the expense of their long-term health.

But an employee at Central States doesn’t care about one good quarter, they care about a good 10 years, and a good 50. If the company’s products turn out to be inferior next year their stock in the company will tank, if the company goes bankrupt in 20 years it will go down to zero. It’s in their best interest to act in the long-term interest of the company, and to grow it sustainably rather than quickly.

“One of our CEOs likes to say that these companies are not looking to hit home runs, they're looking to hit singles and doubles on a regular basis,” Montaño tells me. “When the C-Suite goes into work every day, they see the receptionist, the person on the factory floor, the guy who's building the building or digging the ditches, and they know that those are the shareholders they are responsible for. They take that seriously.”

Every month, Central States executives share the company’s P&L with employees, and every year they share the financials of the business at annual shareholders meetings, where employee-owners can participate in discussions about the future of the company. After a new plant was struggling with sales in its second year, one employee-owner raised his hand at a shareholder meeting and said, “This isn’t helping our company, and it’s not helping my share price, can we discuss the closure of this plant?”

“It was a great conversation, I love the fact that it’s not somebody else's problem,” Ruger says. “They're thinking like business owners which is what you want, right?”

It’s worth noting: Employee-owned companies are not cooperatives. “We are employee-owned, not employee-run,” Ruger clarifies. Business decisions are still made by executive leadership even as employees are incentivized to help the company become more successful.

As a result, ESOPs are generally healthier companies. “These companies do better at employee retention, they do better at retirement benefits, they default less often on loans,” Montaño says. “Our companies did better during the Great Recession, they did better during Covid.”

There are serious benefits to the company for operating this way. ESOPs are a viable alternative to unions—there is no rift between the owners and the workers, workers are the owners! They are also exempt from paying income tax—though they tend to spend those dollars on their employees instead.

“It helped us grow when we were smaller. Now that we're larger, what we're paying out each year to our employee-owners is probably more than we would pay in tax, quite honestly,” Ruger says. “But if I have to choose who we pay our money to, I'd rather pay employee owners than give it back to the government. I think it's probably the right way.”

He brings up a good point. I’ve mentioned before that I do not think the answer to our wealth disparity is to “tax the rich.” Don’t take Jeff Bezos’ money and give it to the government, better distribute Amazon’s earnings among its employees—not just to its founder.

“I think our taxes are way too burdening and we don’t do a good job using the money. I wouldn’t mind paying more if we were using it well, I just don’t know if we are,” Ruger says. “Why redistribute the wealth after it’s already been earned, why can’t we earn it beforehand? It naturally levels out the haves and have-nots.”

It’s worth noting that the “haves” still benefit from this equation.

“Most ESOP companies start because the founder wants to exit or cash out, but they don't want to sell to a private equity firm that will run their company into the ground or slash and burn employee headcount,” Ware says. “A lot of owners built a company and were in the trenches with the people beside them. They want to take care of them, but they also want to cash out. A good option is to set up an ESOP, and that's exactly how Central States got started.”

Carl Carpenter founded Central States in 1988, but sold it to his employees when he retired in 1991. More specifically: He sold a portion of the shares of his company to an ESOP trust, which holds the company's shares on behalf of the employees. In 2011, the company bought the remaining shares and became 100% employee-owned. Carpenter sailed into the sunset with a nice retirement package even as he allowed his employees to start building their own, and I don’t see why every founder shouldn’t do the same.

“There are real benefits for an owner turning the company into an ESOP,” Ruger says. “They personally benefit from the sale when they exit the business. Additionally, there are some real tax benefits to turn it into an ESOP—they pay a whole lot less taxes when they sell the company.”

The only reason they don’t do it more often is because they don’t know about it. “The number one issue is education,” Montaño says. “If you're looking to sell your business and you go to your accountant or lawyer, they may not say ‘Have you thought about an ESOP?’”

It’s also not a quick process—founders interested in selling to their employees need to plan ahead. A feasibility study needs to be conducted to ensure the viability of an ESOP plan and an independent valuation of the company needs to be conducted to determine the fair market value of the shares. A trust needs to be defined and structured, and a trustee appointed to oversee it on behalf of the employees. “If an owner just wants to get out, an ESOP is not for them,” Montaño says.

That might be changing, ESOPs have bi-partisan support in Congress and moves have been made to improve education about ESOPS and make the transition easier for founders. “We have support from Members of Congress across the political spectrum.... It's capitalism at its best,” Montaño says. “A year and a half ago, there was legislation mandating the Department of Labor to open an Office of Employee Ownership, and they've taken a more robust interest in ESOP companies and recently appointed someone from the employee ownership community to this important role.”

In 2022, only 34 percent of families in the bottom half of income distribution held stocks, while 78 percent of families in the upper-middle-income group did—95 percent of families in the top one percent held stocks. But employee ownership changes that equation. As the process becomes easier and education about ESOPs grows, more and more founders will exit by selling their companies to their employees, and the result is that more and more of the wealth will be owned by everyone who works, not just the person they work for.

As the stock market gets richer, so will we all, and that’s a future I’m excited about working toward.

“I'd love to see it more and more and more,” Ruger says. “It's really generating wealth for people, I’m convinced we're going to change generations.”

This is a continuation of my capitalism series which is figuring out how capitalism can work better for everyone while serving as research for my utopian novel. I hope you’ll join us in the comments for further discussion!

Thanks for reading,

P.S. If you enjoyed this post, please share it or recommend my work to your subscribers! That’s how I meet new people and earn a living as a writer. Thank you so much for your support.

This is a great review of Central States and ESOPs. Another one of my favorites is Bob's Red Mill. It is interesting though, that the industry liked to call Bob a 'philanthropist' and not a 'businessman'. When asked why he did an ESOP, it is basically because he felt it was the 'right thing' to do for the employees, some of whom he had worked together with for 30 years. That is beautiful, and yet I think there is something in that detail that needs further uncovering. Was he a philanthropist, or a smart businessman who cared about the legacy of his product? You could easily say that Bob was not so much motivated by profit as he was motivated by the meaning of his work, and I have met many other successful business owners who claim the same.

But how do you convince a person who is strongly motivated by profit, to do something that would lessen their personal financial gain? One way, which you hint at here, is that if the 'legacy' of a company is important to the owner, employee ownership is a logical way to keep a company going with its heart and soul intact. I think the track record is quite strong for ESOPs in this manner, especially when they aim at 100% employee ownership. If I am not mistaken, Bob's Red Mill doubled their profits after they moved to employee ownership.

As usual in reading your work, a lot to chew on. Thanks for these deep-dives!

I currently work at an Employee Owned Company and when they say one of their values is that employees come first they actually take it to heart. There's also a lot more attention from everyone in the company to lean in and push because waste directly impacts their salaries. Everyone has skin in the game as Talib would call it.