How Silicon Valley got rich

And how everyone else can get rich too.

This essay is research for my book We Should Own The Economy, which I’m writing in public. Readers can still invest in the project and earn a share of the revenue when it sells 👇🏻

In 1957, eight engineers left their former semiconductor company and convinced Sherman Fairchild to back a new one. This was unusual at the time; entrepreneurship wasn’t a readily available path, and angel investment a rarity. But the Eight had a proven track record and Fairchild was a wealthy heir with a passion for science—he agreed to give them each a tenth of the company plus $1.5 million in corporate funding, so long as he retained the option to buy out their shares for $3 million.

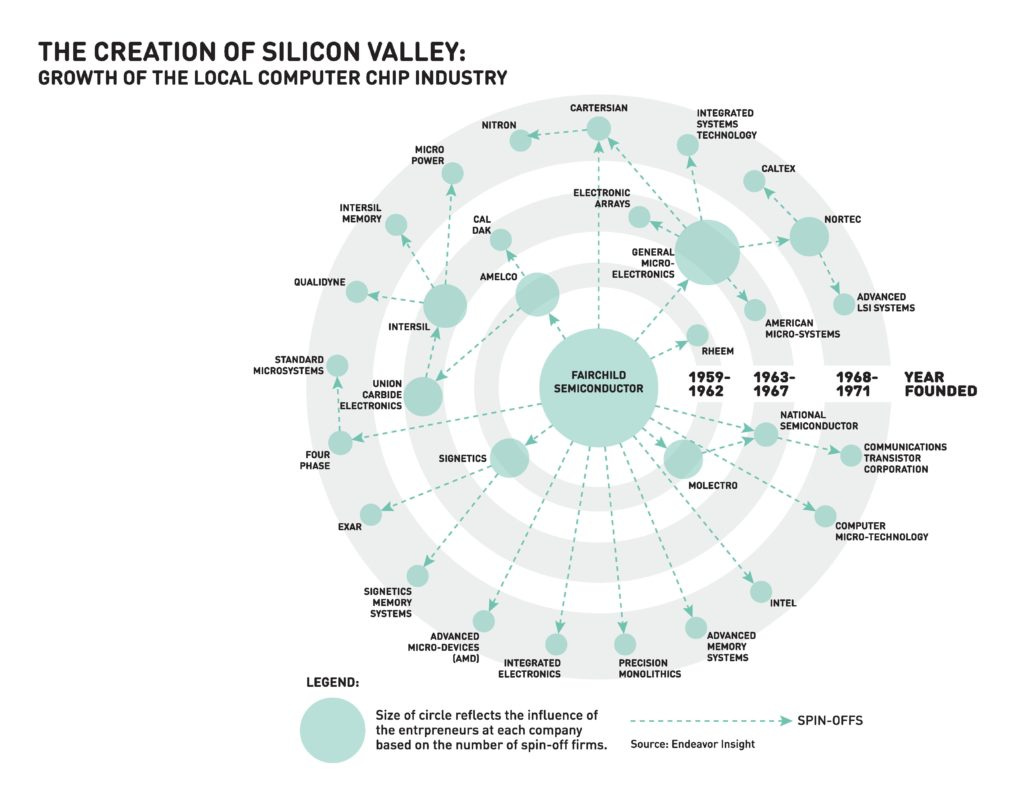

Fairchild Semiconductor began in a garage in Palo Alto, and within two years they had revolutionized integrated circuit technology using silicon. They created “the chip” that would power Silicon Valley and give it its name. The Eight became Silicon Valley entrepreneurs and Sherman Fairchild became one of its first venture capitalists, creating a prototype later investors would institutionalize.

They also became rich.

By 1959, Fairchild Semiconductor was worth $100 million and Sherman Fairchild exercised his option to buy the company for $3 million. He made out with $97 million in corporate value, while the Eight earned $300,000 each for their shares and learned a valuable lesson in equity ownership. Seven of the eight used their earnings to found new tech companies, including Intel, and one became a venture capitalist who funded dozens of companies. All of them created employee stock ownership programs that rewarded founders and early employees with equity.

Known to history as the “Traitorous Eight” for leaving their former company to start Fairchild, the team not only pioneered the chip that would create Silicon Valley but also the equity plans that would become a tech standard. Silicon Valley would mint generation after generation of employee-owned tech companies, with entrepreneurs getting rich from one company and then moving on to found another.

Lured by the idea that they could earn equity in the companies they helped build, engineers flocked to California to participate.

This caused a massive shift in equity ownership. In the early 1950s, only 4.2% of US households owned corporate stock. Companies were largely owned by wealthy industrialists like the Rockefellers, Du Ponts, Mellons, and their heirs; as well as early investors in companies like IBM, GE, and Ford. Sherman Fairchild, incidentally, was heir to the IBM fortune. Then, the Revenue Act of 1950 allowed profits from stock to be taxed at a lower “capital gains” rate (25%) rather than an income tax rate (as high as 91%), making it an effective incentive for high earners. In 1950, virtually no executives were earning equity as part of their compensation packages, but by 1951, 18% were. That’s when Fairchild Semiconductor came in.

As tech companies proliferated throughout Silicon Valley in the 1970s and 80s, so did their stock plans. Reagan-era tax policies further incentivized employee equity, allowing shareholders to defer tax payments until stocks were sold and reducing the taxes paid when they were. As more employees were paid in equity, more of them got rich. When Apple went public in 1980, it created 300 millionaires. When Microsoft did in 1986, 3,000 employees became millionaires. After Google’s IPO in 2004, 1,000 employees held stock worth more than $5 million. By 2007, even employees who had been at Google for a year owned about $276,000 in stock value on average.

As entrepreneurs and executives grew rich from their exits, they founded even more companies or funded them as investors. When PayPal sold in 2002, it famously made megamillionaires out of its executives and launched a new era of Silicon Valley: Peter Thiel used his riches to found Palantir and invest in Facebook, Elon Musk founded Tesla and SpaceX, Reid Hoffman founded LinkedIn, three engineers founded YouTube, and two others founded Yelp.

Employee equity programs created a new entrepreneurial class and fostered a generation of employee-owned companies.

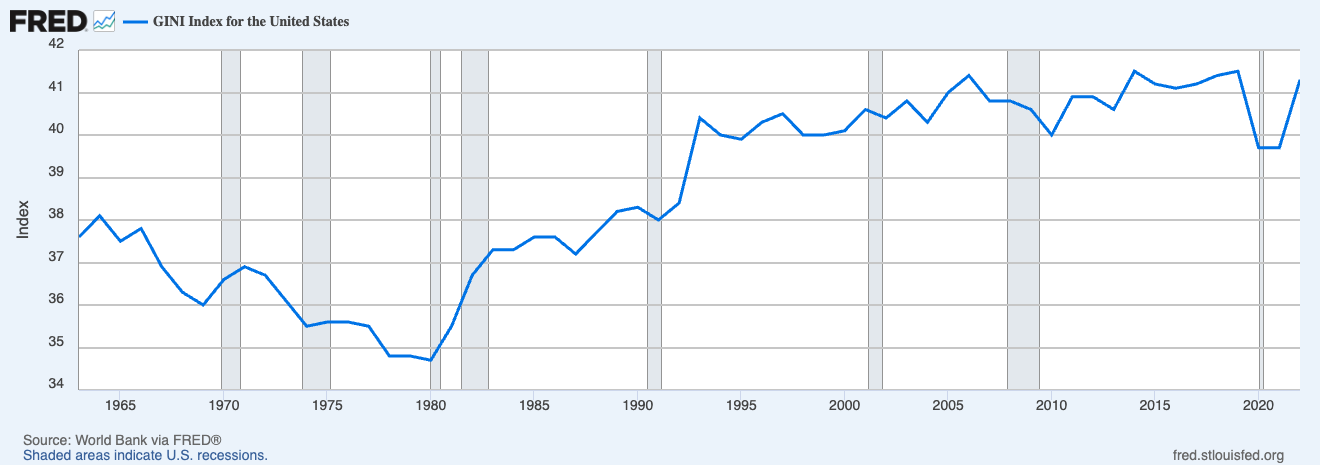

They also led to rampant inequality.

At the same time that workers began earning equity in companies, executives began earning way more equity. Between 1978 and 2023, typical worker compensation grew by 24%, while CEO compensation grew by 1,085%. In 1965, CEOs were paid 21 times the typical worker, but by 2023 CEOs were paid 290 times the typical worker. If a typical employee might see $200,000 in stock gains throughout their career, a CEO might see $50 million, far outpacing any gains made by the middle class.

A Clinton-era reform tried to fix the problem, placing a cap on executive salaries at $1 million, but this only caused a larger share of executive compensation to come in the form of equity, unintentionally making the problem worse. When we compare the rise of CEO pay to the rise of the stock market, we can see the one is directly causing the other.

Investors profited most of all. Just as Sherman Fairchild was the real beneficiary of Fairchild Semiconductor, so would the investor class own the largest share of every company on the stock market and thus gain most of the economic value. As a 2021 Harvard study points out: “The wealthiest 10% of Americans own 94% of business wealth, 92% of directly held shares of public companies, and 93% of stock mutual funds.”

As our companies grew, those with equity in them got rich while those with little to no equity didn’t. When the stock market boomed, the wealth of the bottom half barely increased while the wealth of the top half skyrocketed.

Today, the Gini Index, which measures inequality over time, shows the US has reached historical highs. The index ranges from 0, where everyone has exactly the same income, to 1, where one person has all the income and everyone else has none. Inequality was improving until the 1960s and 70s and that number was going down, but as the top earned more of their income in equity and the stock market grew, the gap widened and it went up. The US has the highest Gini ranking of any developed country.

It could have been much worse.

Without Silicon Valley cutting employees in on the deal, all of our economic value could have funneled to the top instead of just nearly all of it. Before 1950, nearly 100% of corporate value went to the wealthy investing class. Today, 70-99% of public companies are owned by nonworking investors, with 1-30% owned by workers. Employee ownership has been an important and countervailing force, chipping away at inequality by putting wealth in the hands of workers, but it’s not enough.

Our task now is to drastically expand what Silicon Valley started: To increase the share of companies owned by working employees and to increase the share of worker equity that goes to non-executive employees.

That Harvard study modeled what that could look like. If all US businesses were 30% employee-owned, the Gini Index would decrease by nearly 10%, and income inequality would be at its lowest since we began tracking it in the 1960s. The median household net worth would double, from $121,760 to $230,076, and the bottom 20% by income would see their wealth quadruple, from $10,060 to $40,000 on average. The wealthiest 1% of Americans would see their net worth decline by 14%—from $28.4 million in assets to $24.4 million—but the wealthiest 90 to 99th percentile would see their wealth decline by only 1%.

In other words: By granting more equity to workers, we’d see only minor decreases in wealth at the top, but exponential gains in wealth at the bottom.

To do this effectively, departures will need to be made from traditional Silicon Valley stock plans where shares are allocated disproportionately to nonworking investors and benefits shared only in the case of an exit. The Harvard study assumes an ESOP structure, where shares are distributed based on an employee’s compensation level and allocated regardless of liquidity.

This is important.

Most corporate equity programs come in the form of Restricted Stock Units (or RSUs). Employees earn a set number of shares over their first four years, but those shares are worthless unless the company eventually sells or goes public. Exit events are unlikely: Seventy percent of startups fail within their first 10 years; of those that succeed, only 30% will be acquired and 1% will go public. Exits become more likely with more fundraising rounds, but shares get diluted and are inequitably distributed: By the time of an exit, 40-60% of a company is typically owned by investors, with 20-30% owned by a small group of founders and executives, and the remaining 5-20% shared thinly between hundreds or thousands of non-executive employees.

Employees who join already public companies have the opportunity to buy company stock at a discount through an Employee Stock Purchase Plan (or ESPP). An employee with a 15% discount could purchase $10,000 worth of stock and instantly own $11,765 worth—if they turn around and sell they’ll gain $1,765 before tax. This, however, provides the employee with a small and very short-term gain. A 10–15% discount on a few thousand dollars per year is the most an employee can expect to gain, and thus does not meaningfully shift equity into their hands. Conventional financial wisdom is for employees with an ESPP to buy and sell stock quickly, then use the gains to invest in index funds.

RSUs are a good thing, but they are a lottery ticket. ESPPs are good too, but only mildly increase equity ownership for the average employee. Both inequitably benefit investors and executives and give very little stock to working employees by comparison.

At a company with an Employee Stock Ownership Plan (or ESOP), however, shares are worth something immediately, even at privately owned companies. Every year, a third party calculates the value of the company and employees know exactly how much company stock they have and how much it’s worth. Whether the company stays private, sells, or goes public, employees can cash out with the value in their account. And shares are distributed equitably, based on salary level: An employee with an annual salary of $100,000 earns twice the shares of someone who earns $50,000, and only the first $345,000 of compensation is counted on this scale. If the lowest-paid person earns $50,000, the highest-paid person can earn a maximum of 7x more in shares.

ESOPs give equity to employees regardless of liquidity, and shares are more equitably distributed between the top and the bottom, but there’s a major downside: Those shares go into a retirement account rather than an investment account. This eradicates the Fairchild effect: An employee with an ESOP can never cash out and start another ESOP company. They can only retire at 65 and sail into the sunset. That model won’t proliferate the way Silicon Valley has, and those riches won’t go on to benefit the economy at large, just individuals who can own a nice home and have a larger savings account for retirement.

This is a huge miss to me. Especially since 90% of employees with an ESOP account also have a (more diversified) 401(k) account.

If we want to create more equity owners, corporate equity needs to be distributed into personal investment accounts, not retirement accounts, just as investor and executive shares do. Individuals should be able to use those gains to start new businesses and fund existing ones, and see their wealth grow and proliferate into more employee-owned companies, just as Silicon Valley has. The goal here is to create more owners of the economy, not limit who can benefit from it to the already wealthy and the retired.

This has led to a more modern version of the ESOP: The Employee Ownership Trust (or EOT). Here, a company puts 51% to 100% of corporate shares into a trust owned on behalf of employees. As the company earns profits, the board of directors decides how much to reinvest in the business and how much can be distributed to the trust (owners). Employees receive a share of the trust as an annual cash bonus. This is a great option for small businesses who want to share profits with contributors, but individuals don’t become equity owners the way they would with an RSU, ESPP, or ESOP, and they lose access to that bonus and ownership if they leave the company.

It seems to me that all of these models should learn from each other. Why couldn’t employees earn equity in their companies at a more equitable rate, regardless of liquidity, just as they do at ESOPs? Why couldn’t they also cash out their shares and start new businesses with their earnings, just as they do with RSUs or ESPPs?

The Fairchild Eight paved the way, and Silicon Valley proved how motivating it can be when those who labor to create corporate value also share in the benefits of that value as owners. Now we need that equity to benefit more than just a few. We need to give employees a larger cut of corporate equity than we have been, and we need to give nonexecutive employees a more equitable share. We need to improve the equity plans we’re currently offering to make this a better all-around deal for everyone and create more owners of the economy overall.

I’ll be sharing more ideas about how we can do that shortly. In the meantime, I’d love to know your thoughts 👇🏻

Thanks for reading,

P.S. This chapter has been added to the public manuscript for my book which can be found here.

P.P.S. There are two important questions implied in this essay that need to be addressed: Why is inequality bad? (As in, does it matter if the rich get exorbitantly rich so long as everyone is still getting richer?) And what about public attempts at creating more owners of the economy through IRAs, 401ks etc.? These will be addressed in future articles.

P.P.P.S. Mandatory Disclosure regarding that link at the top: The Elysian is "testing the waters" to gauge investor interest in an offering under Regulation Crowdfunding. No money or other consideration is being solicited. If sent, it will not be accepted. No offer to buy securities will be accepted. No part of the purchase price will be received until a Form C is filed and only through Wefunder’s platform. Any indication of interest involves no obligation or commitment of any kind.

Further reading

Here are a few notes from the margins of my research:

For more background information on the ideas in this article, here are a few things I’ve already written on the topic:

A few ways we can expand employee ownership: “120 million employee-owners in one generation”

More about ESOP structures: “Every company should be owned by employees”

The Intel Trinity by Michael Malone

How venture capital built Silicon Valley, from NPR

The history of employee stock options, by Frederick Mijinhardt

“Executive Compensation” by Kevin Murphy

This was well done. I did not realize what a diversity of employee stock ownership types there are.

Elle, this a brilliant reframing of how Silicon Valley's most impactful innovation wasn't necessarily the microchip, but rather more about the democratizing of ownership itself. (Sidenote: having had the privilege of learning from you during Write of Passage, I'm not surprised by the depth and clarity you bring to such a complex topic. Your generosity with insights and time during that cohort really showed, and it's evident here in how accessibly you've made these economic concepts. Looking forward to the book and your continued posts.)

Obviously your essay touches on the fundamental tension in capitalism itself: between rewarding capital and rewarding labor. The "Fairchidren" family tree you reference shows how wealth begets wealth in an almost exponential way. But your proposed solutions suggest we might be able to harness that same exponential effect for broader prosperity...

I'm curious to learn more about how you think about the underlying challenges:

- Political Feasibility: Given how entrenched current equity structures are, what would it take to create momentum for more equitable distribution? The Clinton-era salary cap backfired spectacularly—how do we avoid similar unintended consequences?

- The Innovation Question: Silicon Valley's current model, inequitable as it is, has generated tremendous innovation. How do we ensure that more equitable distribution doesn't dampen the entrepreneurial dynamism you describe?

- Implementation: For companies wanting to move toward more equitable equity distribution today, what would you recommend as practical first steps? (I believe you've written a lot on this - I need to dig in)

Thanks for sharing. Great read.