Multi-country civilizations are good, actually

A vibe shift in favor of annexation would be counterproductive 🌏

I.

The year is 2033, and a unit of the People's Liberation Army has just stormed the Presidential Office in Taipei, forcing the President of the Republic of China to surrender. Thus ends the full-scale invasion of Taiwan that Xi Jinping, recently elected to a fifth term as General Secretary of the Chinese Communist Party, has long dreamed about.

From afar I follow the news, and wonder: why? What was the point of this? Who will actually benefit?

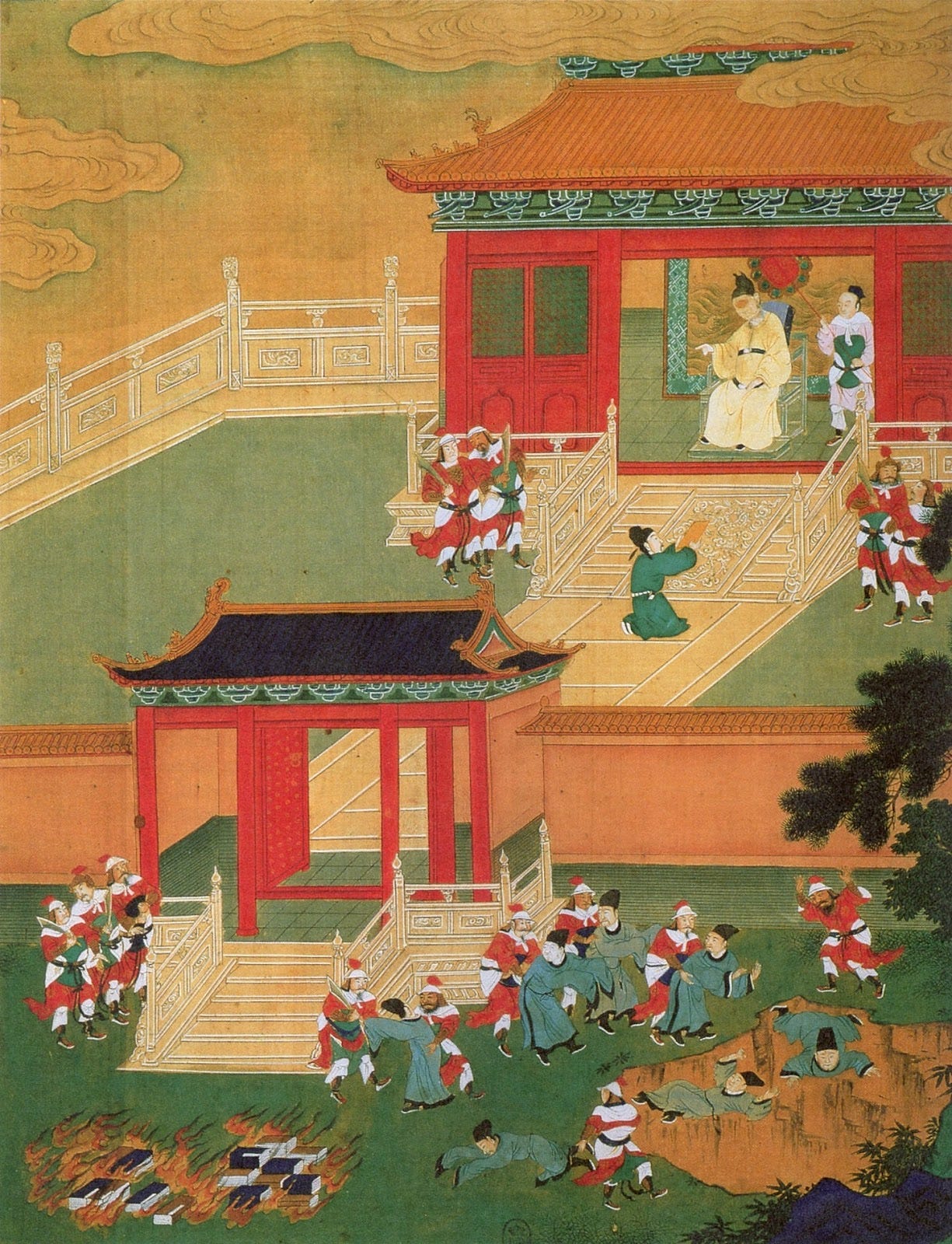

The obvious answer (I suppose as I write this hypothetical future timeline in 2025) is Xi Jinping himself. And, more generally, the government of the People’s Republic of China. Taiwan is the one rebel region of China that didn’t fall to Mao Zedong’s communist army by the end of the civil war in 1949, so the Communist Party has maintained a historical claim on the island. Historical claims are kind of a weak reason to do anything, but some people care about them a lot. And so the PRC came up with its “One China” policy to justify its attitude. Annexing Taiwan would be strategically useful. It would fulfill one of the Communist Party’s core promises. Xi Jinping would forever be remembered as a glorious leader who completed yet another unification of China, following the legacy of emperor Qin Shi Huang in the 3rd century BC. I guess.

But other than that, who would gain anything? Not the people living in Taiwan, who feel more Taiwanese than Chinese, and a large majority of whom oppose being reunited in China even with a “one country, two systems” situation like in Hong Kong. Not the ordinary people living in the PRC, who are more divided on the question but would certainly suffer from the hazards of war: economic disruption, isolation of China from the rest of the world, casualties from the conflict. Not proponents of democracy, for whom Taiwanese governance is a shining success story. Not the semiconductor industry, of which the most important company in the world, TSMC, is based in the city of Hsinchu. Not the people using the outputs of the semiconductor industry, i.e. every person on Earth who owns an electronic device. Not anyone living in an economy, since a major war involving China would necessarily wreak havoc basically everywhere.

So an invasion of Taiwan would be a pretty bad deal overall. Still, as I try to steelman the case, I find one thing that could seem worth paying all of that for. Something that Xi Jinping and his ilk presumably care a lot about, more than they care about Taiwanese people, foreign owners of iPhones, or the welfare of their fellow citizens: the long-term flourishing of Sinic civilization.

I imagine 2033 Xi giving his victory speech from the National Palace Museum in Taipei, a location chosen to symbolize the reunification of Chinese culture. Yes, it seems plausible that that is what he wants. No more centuries of humiliation: China is back into the game, ready to contribute more culture and technology to humanity than any other civilization. And yet. And yet! I cannot help but think that he operates under a tragically flawed model of the world. Invading Taiwan is one of the worst actions that China could take to ensure that flourishing. The political unification that it desires is overrated; it is, in fact, good that Sinic civilization consists of multiple countries (and quasi countries). The Chinese-speaking world is a more dynamic place, and a wealthier one, when regions and cities like Taiwan, Singapore, Hong Kong, or Macao (and hypothetically, Tibet and Xinjiang) are allowed to do their own thing, separately from the big motherland of continental China.

This is such an obvious point to me that it feels almost silly to write an essay about it. But it doesn’t seem to be obvious to Xi Jinping. Or, for that matter, to other world leaders such as Vladimir Putin and Donald Trump. Perhaps even more worryingly, random people joke about annexation somewhat more often these days, suggesting some sort of vibe shift in favor of imperialism and against the independent existence of small nations. So maybe it’s worth pointing out that the common wisdom of the past 75 years is correct, and that annexation is really, deeply, a bad idea.

II.

There’s a popular narrative, notably developed in Jared Diamond’s Guns, Germs and Steel, that Europe managed to take over the world because, contrary to China, it was disunited.

According to this model, the many peninsulas, islands, and mountain ranges of the European subcontinent encouraged the formation of multiple small kingdoms instead of one large empire, and those kingdoms competed with each other in a way that was beneficial in terms of technological advances and colonial ventures. In China, a single bad decision at the highest levels could stop progress for a century. In Europe, even if the king of Portugal decided that sending ships out west was stupid, the queen of Spain might like the idea enough to make it happen.1

Reality is, of course, more complex than this basic story. For one thing, China was sometimes very disunited too, and several of its historical eras bear names like “Sixteen Kingdoms” or “Five Dynasties and Ten Kingdoms”; and conversely it did manage to advance technology during periods of unity like the Song dynasty. For another, the Roman Empire shows that the peninsulas of Europe can totally spend centuries under the yoke of a single centralized state. But the core argument is correct. Smaller political entities regularly outperform larger ones along important metrics like innovation and cultural production.

Thus the city-states of Ancient Greece—despite frequently going at war with one another—are where the Western world was born, together with developments in philosophy, theater, classical architecture, mathematics, and democracy. The city-states of Renaissance Italy — despite frequently going at war with one another — are where Western civilization recovered after the slowdown of the medieval period, rediscovered the classics, developed modern banking, and revolutionized art. Elsewhere in history, there are many examples of dynamic disunited civilizations, from the Mayas and the Valley of Mexico altepetls in pre-Columbian Mesoamerica, to Mesopotamia and Phoenicia in the ancient Middle East, to the Hanseatic League and the many lordships, duchies, electorates, prince-bishoprics, margraviates, free cities and other states of medieval and early modern Germany.

Still, one might reasonably point out that city-states have been less successful, along metrics such as longevity or raw population numbers, than another major form of political organization: the empire. Most people who were alive between antiquity and the 20th century were the subjects of an empire. Empires take many forms, but usually the word refers to a vast, multiethnic entity, in which an imperial core rules over peripheral regions with degrees of autonomy varying between “none” and “a lot.”

Empires definitely have advantages over city-states and petty kingdoms, which is why they have been a successful form of political organization. Arguably, their most important benefit is to provide a solution to coordination problems. When multiple city-states can’t agree on how to exploit a shared resource, they will enter conflict, which is usually bad for all parties involved. But if both cities are part of an empire, the imperial government in Rome or London or Kaifeng can step in and use its authority (and army!) to allocate the resources as it sees fit. The cities might grumble that they get the short end of the deal, but without an army, what are they gonna do about it.

So the result is stability and peace.2 Pax Romana, Pax Mongolica, Pax Sinica, Pax Britannica, and so on. This is a pretty good thing.

And yet, since the beginning of the 20th century, empires have been on the way out. The First World War annihilated the Austro-Hungarian, German, and Ottoman ones. Later, the colonial empires of the European powers (mainly Britain, France, Italy, Portugal, the Netherlands, and Belgium) were almost entirely dismantled through the process of decolonization, creating dozens of new countries in Africa, Asia, Oceania, and the Caribbean. The arguably imperial Soviet Union, a successor to the Russian Empire, disintegrated in 1991. The only remaining emperor in the world is Naruhito of Japan, but his title is a relic: since 1947, Japan has been a constitutional monarchy and a nation-state, not an empire.

I suspect that the deep reason empires have declined and transitioned to other forms of organization—mostly nation-states—is that there is less “need” for them in terms of solving coordination problems. Thanks to telecommunications, global standards, international organizations like the United Nations or the European Union,3 and widely integrated trade networks, coordination can now happen between numerous small states and companies without having to rely on a single powerful guy to enforce the common interest.

This is good, because empires turn out to be problematic along quite a few axes. People don’t typically like being ruled by an imperial core that might be culturally very different from them. The enforcement of empire-wide standards can be detrimental if those standards are poorly chosen. And though some empires have allowed a high degree of autonomy to their outlying regions, sometimes approximating the city-states model, an empire can also decide to be extractive and keep the periphery in poverty as it diverts its resources to the core.

Worse, even when an empire tries to rule the peripheral regions fairly, it may be structurally incapable of maintaining the peace for long. Jane Jacobs, a thinker who wrote on how cities are the only true economic engines, thought that empires and large countries inevitably decline because they bundle thriving cities with less economically dynamic ones. An independent Athens, Venice, or Hong Kong can become wealthy and culturally productive because it is independent and has its own policies, currency, and exports and imports, which can all dynamically adjust thanks to tight feedback loops. But when it becomes part of the Roman Empire, the Austrian Empire, or the People’s Republic of China, the feedback loops now apply to the entire empire or nation, which dilutes the signal and slows down the response. A large country cannot feasibly adjust its policies in currency, trade, etc. in a way that benefits each of its cities. It furthermore has an incentive to transfer economic resources from the wealthy cities to the poorer regions, through military expenditures (e.g. to discourage rebellions) or welfare programs (whether out of genuine concern for the poor regions or for instrumental reasons, like winning elections or avoiding separatist sentiment).

Thus, given enough time, most dynamic cities in a large country decline,4 and the golden goose is killed. Jacobs thought that this is why all empires thus far have eventually degenerated and collapsed.

III.

Sometimes people describe the United States as an empire. Its military power is unmatched, with more aircraft carriers than the rest of the world combined and three times the military expenditures of its next rival, China. It is the policeman of the world. We all live in Pax Americana.

But this is merely a metaphor. The US isn’t really an empire. It exerts its tremendous power in other ways, through commerce, culture, and diplomacy; and it hasn’t been in the business of acquiring new territories since 1898, after the Spanish-American War and the annexation of Hawaii.

At least until now. Is this essay about Donald Trump? Sure, I guess it’s about Donald Trump. For the purpose of making it evergreen, let us remind the reader that in early 2025, at the beginning of his second presidency, Trump floated the idea of annexing new lands on the American continent:5 Greenland, the Panama canal, Canada, Mexico. To be clear, all of them are unlikely to happen, since very few people in Greenland, Panama, Canada or Mexico want to be annexed by the United States. But Trump’s actions are hard to predict, so I wouldn’t be that surprised if one of those annexations ends up materializing.

What worries me most, though, isn’t Trump’s antics; it is the fact that an imperialist US has become a somewhat more culturally accepted idea. I have seen many friends and people I respect—almost always people from the US, of course—come out and say that they like some of the above. Annexing Greenland is “strategically important.” Absorbing Canada would be “a good deal for Canadians.” Directly controlling the Panama canal would “prevent a Chinese takeover.” On the less serious side, I routinely see calls for some sort of unification of the Anglosphere, under the assumption that it is an accident of history that the developed6 English-speaking countries are separate.

But the same logic applies here as for China and Taiwan. It is good that the Anglosphere consists of several countries instead of just one. When any of its members err, the others can come to the rescue by trying and displaying superior ideas. When one of them gets stuck with some suboptimal policy, political experimentation in one of the others can be noticed and copied—and more readily than they can from a very different country speaking a different language. The feedback loops informing the state of the economy in Toronto, London, or Melbourne are tighter than they would be if those cities were in the same country as New York, Washington, and San Francisco. As for Greenland and Panama, I can’t imagine either of them benefiting economically from becoming a tiny, faraway, and non-English-speaking peripheral region of what it would be more and more reasonable to call the American Empire.7

As Robin Hanson writes, cultures can become maladaptive. The only remedy against cultural drift is to have somewhat isolated cultures doing their own thing. Language barriers are one way this isolation can happen; another is political independence. Since the Anglosphere, by definition, doesn’t have the first, there is value in maintaining the second.8

Now, it is certainly possible that unifying the Anglosphere wouldn’t be that bad. The United States itself is a big place that has marvellously succeeded as a country. I think this is due in part to the US federalist model: its constituent states have a lot of autonomy. Many of them are quasi-city-states (a major urban area surrounded by a hinterland). Plausibly, if this model were followed at a larger scale, it would turn out fine.

But I prefer to think that the Anglosphere, and the world, can solve their coordination problems in other ways. We have treaties; we have NGOs; we have trade agreements. Instead of annexing Greenland, the US can simply make a deal with Denmark to build military bases there if it cares about “strategic reasons.” (Incidentally, there is already such a base.) Instead of bullying Canada with tariffs to encourage it to give up its sovereignty, the US can simply, you know, sign a free trade agreement with Canadians if it wants access to their natural resources. (Incidentally, there is already such an agreement.) This way, we get the cultural benefits of independence and the benefits of being able to coordinate around important security or economic questions.

IV.

Discussions of this sort tend to make people somewhat uncomfortable. Taken to its logical conclusion, the idea that small states and city-states are superior to large nation-states and empires suggests that we should be tolerant of, or even encourage, separatism. But most people don’t like separatism, especially when it isn’t tied to a colonial situation or ethnocultural tension.

As a separatist myself, I have long pondered why. Leaving aside the practical concerns of any given separatist movement (economic and military viability, local politics, etc.), I think the cultural and psychological reasons why people tend to instinctively oppose separatism, even for regions they have little connection to, come down to a few elements:

Violence: separatism is often associated with civil war or other armed conflict. The breaking up of Yugoslavia into multiple separate Balkan countries led to quite a lot of violence. So when people complain that tolerating separatism in Spain or Italy would lead to “the Balkanization of Europe,” this is what they have in mind. Many countries around the world have had unpleasant past experiences with separatism, such as the US Civil War, Basque terrorism, or the Biafran War in Nigeria.

Past prestige: larger countries have more resources at their disposal, so they can put up amazing displays in their capital or other strategic locations. Palaces, monuments, grand places of worship, festivals, commissioned works of art, prestigious universities, powerful state-backed industries, successes in international competitions like the Olympics—these are a few ways that a state can make people forge positive associations with it. Smaller countries are, on average, not as able to compete, so they end up with less prestige.9

Complexity: a world with many small states is harder to think about! This is my pet theory: conceptualizing a world with more entities in it is more cognitively taxing, so we are instinctively drawn to scenarios where there are fewer countries, fewer people in charge, fewer currencies, and less need for complicated coordination protocols. In the extreme, this manifests in a vague desire for world government.10

Status quo bias: most of us just don’t find change uncomfortable. We readily accept existing small independent nations, but the thought of creating new ones is annoying.

This isn’t necessarily a comprehensive list, but I think it covers most of the ground. And yet all of them are unconvincing:

Violence is not a necessary outcome of separatism; regions can secede peacefully if we let them. Jane Jacobs discusses the example of Norway getting its independence from Sweden; other examples include Canada, Australia, Iceland, and Czechia and Slovakia. Besides, violence can just as readily be associated with empires quashing separatism or annexing peripheral regions.

In our industrialized world, wealth is more readily accumulated by innovating and trading than by extracting resources, so smaller states don’t have as much of a disadvantage anymore in terms of commissioning impressive stuff. Singapore with its renowned Changi airport, or the United Arab Emirates building their own Louvre and the largest tower in the world, are clear examples of prestige-building by city-states. What we consider “prestigious” is also in flux. For example, we might consider “quality of life” indices to be a component of modern prestige. As it happens, published lists of most liveable cities tend to be dominated by locations in small countries, like Switzerland, Denmark, Austria, Australia, and the Netherlands.

We have a lot of technology and legal frameworks that can help us deal with complexity. To name one example, it’s quite easy today to buy things sold in foreign currency because we have computer systems that can instantly do the conversion for us. There’s also a good chance that further progress in AI will help us find more ways to understand and process complexity.

Do I need to explain why status quo bias is bad? There’s no particular reason to think that current political boundaries are optimal. Besides, status quo bias applies equally well to imperialism.

Ultimately, I don’t think there’s a strong case to say, in the abstract, that either separatism or unity is better than the other. It should always be a decision based on local context and a cost-benefit analysis made by the people living in a particular region. If the people of Canada or Greenland began thinking that annexation by the United States was in their interest, and, after some public debate, collectively decided to try to make it a reality, good for them! And if the people of Taiwan decide that they prefer to be fully independent of China, then the thing to do with your One China policy is to quietly shelve it away while you embrace the idea of a multi-centric Chinese-speaking civilization.

We’ll see what the future holds. It’s possible that both Trump and Xi’s velleities of annexation are empty posturing, trying to make themselves bigger than they really are so that the other doesn’t get too cocky. Both are surely aware that actual attempts at annexation would likely go poorly. Russia’s attempt at a quick takeover of Ukraine hasn’t exactly gone well.11

But in case the immediate costs of an invasion or trade war aren’t sufficient to deter them, it’s useful to say it and then say it again: we thrive more when we have political diversity combined with willing cooperation. We are wealthier and more creative when we abandon our grand ideas of unity and allow a large number of countries, of all shapes and sizes, to experiment on their own terms. This is the right path for Sinic civilization, and also for Western civilization, and in fact for all of us on this little planet.

This essay is by Étienne Fortier-Dubois, author of Hopeful Monsters. It is part of CITY STATE, a collection of seven writers exploring autonomous governance through an online series and print pamphlet.

In the case of Christopher Columbus, it’s fun to note that the Portuguese court was correct: Columbus had made a major mistake in calculating the westward distance to Asia. To be fair, the scholars at the Spanish court also pointed that out. It’s not totally clear to me why Isabella and Ferdinand eventually gave in and agreed to finance Columbus’s voyage, but it seems to be a combination of Columbus being annoyingly persistent, and the rewards being potentially much larger than the relatively small investment into the expedition, justifying taking the risky bet that the scholars were wrong and Columbus was right. Columbus was wrong, but it turned out to be a productive mistake.

An interesting observation here is that for most of history, innovation wasn’t desirable: it upset the balance and stability that many civilizations have held as an important value. The idea of innovation being good is relatively new. So plausibly, in the past, empires were seen as strictly superior to innovative city-states and their tendency to mess up the cosmic balance all the time.

The European Union gets derided a lot lately; it is perceived in the US and elsewhere as throttling innovation, being unable to respond effectively to threats from Russia, and generally managing decline rather than ensuring a flourishing European civilization. Still, in my view, the EU is a positive institution on balance, since it allows coordination between European countries to an extent never seen before. It errs when it begins acting as an empire, enforcing laws and standards to all countries indiscriminately without the legitimacy of popular sovereignty.

With the possible exception of the capital city, where the resources tend to concentrate and where the feedback loops are most effective since it is where policy is decided. But the capital of an empire full of declining cities is in a precarious position. Over time, its economy may become more and more dependent on bureaucracy and the extraction of resources from the periphery, instead of dynamic trade and industry. When the empire collapses, the effects can be disastrous for the city, as in Rome in the 5th century.

In protest, I have resolved to try avoiding using “America” and “American” to refer to the US only as opposed to the entire continent usually referred to in English as “the Americas.”

It’s worth noting that these proposals almost never include the countries that use a lot of English but are less developed, like India, the Philippines, and many countries in Africa and the Caribbean.

An idea that circulated a lot some weeks ago is that the US could offer each of the 59,000 Greenlanders $100,000 or whatever so that they are all incentivized to join the US. Maybe that would work, but surely this would distort the Greenlandic economy immensely? For one thing, wouldn’t there be massive inflation if everyone has at least $100,000 to spend? Wouldn’t it discourage local investment as people just use their money to import whatever they want? And then Greenland would be forced to use the US dollar as its currency and have virtually no weight at all in the US government apparatus to fix its future economic problems. I’m no economist and I don’t claim to have thought this through, but the proposal strikes me as extremely unserious.

There’s also value in not turning the entire world into an English-speaking one, and being on the lookout for good ideas from non-English-speaking countries.

Even the Parthenon in the city-state of Athens was built using the funds of the Delian League, which Athens led, leading it to be occasionally called… the Athenian Empire.

I have written multiple times about how this manifests in fiction, too (e.g. Middle-earth and fantasy in general, dystopian science fiction, and end-of-the-world scenarios). Imaginary worlds are always far simpler than the real one. I’m not sure if this phenomenon has an influence on how people conceive the real world, but it seems plausible, given the popularity of fictional worlds.

Though it’s too early to say, really. As I write this, the US government seems to be trying to get Ukraine to give up a lot and Putin to be able to walk away with a partial victory.

Excellent essay, clearly written and argued. I'm a lifelong resident of New York City and if there's a place in the United States that's like a city-state, it's here.

What a poor example Taiwan is! Since the Kuomintang escaped to it under the protection of the US military it it has been used as an economic weapon against China (who are still not allowed to use most of the advanced chips produced there). If the USA were not using its existence and its resources continuously to attack China there might indeed be some sense in China coexisting with Taiwan.