The Cooperatist Manifesto that inspired Mondragon

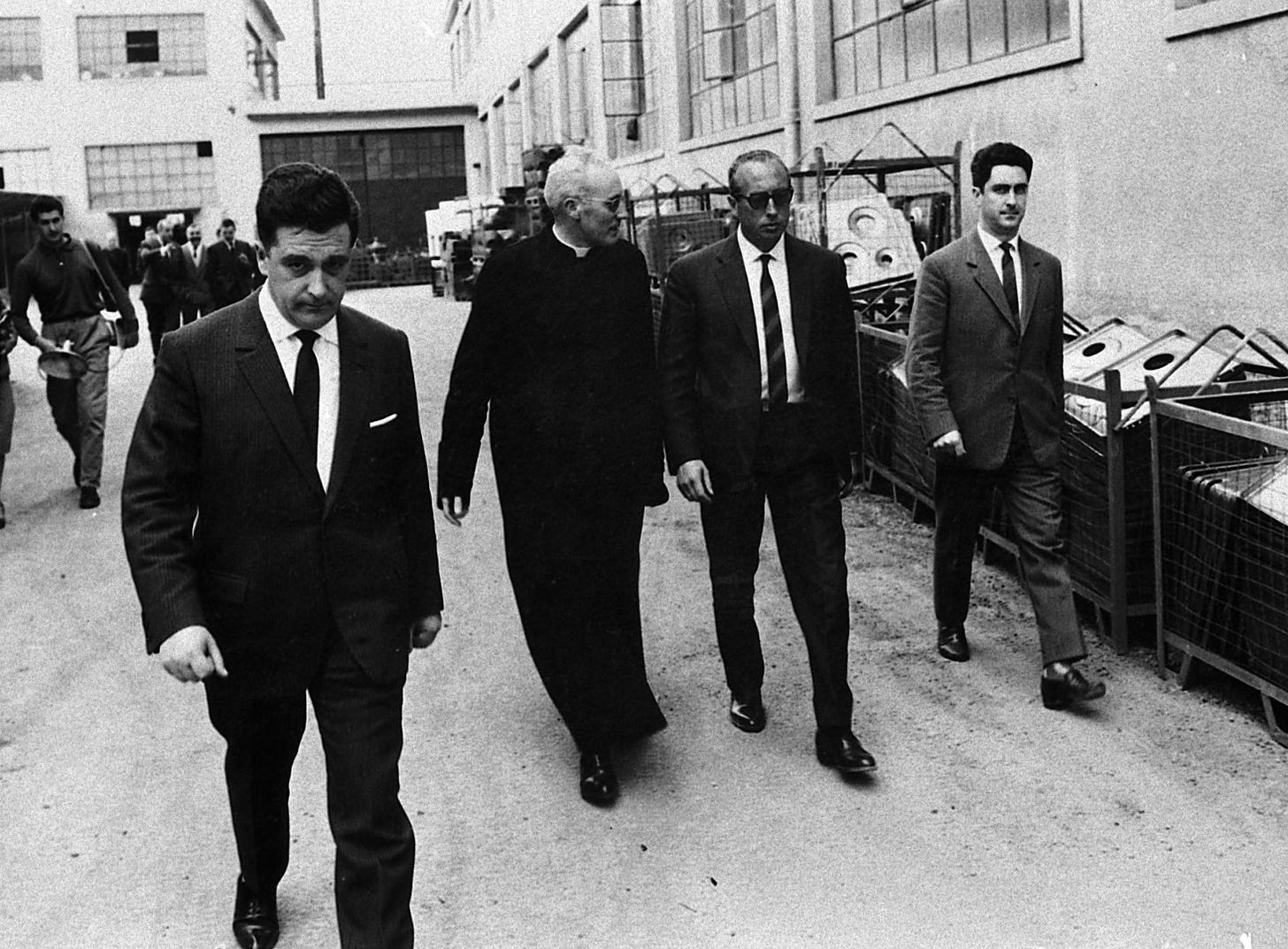

Father José María Arizmendiarrieta didn’t just imagine a better economic system, he built it.

A century after Karl Marx argued for a more fair and just society, José María Arizmendiarrieta started building one.

By 1941, the newly ordained Spanish priest saw the capitalist order sweeping across the world and found it unjust, the owners were becoming rich by the work of the laborers, while the laborers remained poor and destitute, unable to rise up from their lot.

Marx thought we needed to put the state in charge of the economy, at first, before the people could take hold of it themselves, but Arizmendiarrieta thought we shouldn’t get the state involved at all. State control of the economy had turned out disastrous in the hands of Joseph Stalin in the Soviet Union, and Mao Zedong was following a similar blueprint in China.

By the 1950s, Spain was under the control of the nationalist dictator Franco—they didn’t need the government to take over the economy, they needed to take it over themselves. “The worst illusion we can suffer is to become intoxicated with simple words,” Arizmendiarrieta said, and almost in rebuke of Marxism: “It is time for facts and actions and not for so many theories whose practical realization scarcely resembles the fundamental principles they are based on.”

From where he stood, capitalism was creating much more wealth and prosperity than socialism was. In his parish of Arrasate-Mondragón, Unión Cerrajera was the largest company in town, employing nearly all the region’s workers. The locksmith factory was generating plenty of wealth, it just indiscriminately favorited the owners.

Arizmendiarrieta just thought we needed more owners. We needed the workers to be the owners.

“We do not aspire to economic development as an end,” he said, “but as a means.”

Or as Germán Lorenzo, global public affairs for Mondragon, would put it nearly 80 years later: “Profit is like air, we need air to breathe.”

Back then few could breathe easily, but Arizmendiarrieta thought everyone should. He preached these ideas from the pulpit every Sunday and published magazines demanding profits be shared among workers. But he didn’t just pontificate about a new world order or publish his ideas into a manifesto, instead he tried them out in real time and evolved them over the course of his experimentation.

“Theory is necessary, but it is not enough,” he said, “we build the road as we travel.”

And: “Live first, and then philosophize.”

Arizmendiarrieta would go on to found the world's largest group of worker cooperatives, with 92 cooperatives earning €11 billion in revenue and employing more than 70,500 workers. Today, Mondragon cooperatives are working democracies owned and operated by their workers, and federated together to generate wealth and share it more equitably.

But back then, Arizmendiarrieta’s intention was not to save the world with some new ideology, but to help his immediate community, saying: “Needs unite us, ideas divide us.”

In 1940s Arrasate-Mondragón, people needed money, that meant they needed better paying jobs. To raise the income of his city’s population, Arizmendiarrieta started a vocational school for workers who were not accepted into Unión Cerrajera’s apprenticeship program. Then he personally negotiated with the company for 11 of their employees to get an engineering degree while maintaining their jobs at the company.

José María Ormaetxea was one of them. “At the time, higher education was only for those from wealthier classes,” he remembers in his memoir. “One should not forget that there was a kind of stigma about those of us who came from the poorest social backgrounds, the children of workers. The sheer weight of spending all our lives believing that things would always be the same erected an intellectual barrier that blocked any opportunity of taking on other business challenges.”

Ormaetxea was an early disciple of Arizmendiarrieta. “It was that inertia that José María Arizmendiarrieta helped us to overcome,” he said. “He encouraged us with aphorisms like: ‘You can be businessmen too. You too can create employment and wealth without waiting for those who have always done so to subrogate the God-given birth right of every person.’ That was probably the best legacy he left us.”

Ormaetxea and the others studied for five years (starting in 1947), working 55 hour weeks with another 20-30 on their studies. He estimates they spent another 2,000 hours participating in Arizmendiarrieta’s Catholic Action group. As they became more educated, they rose to management positions with good pay, but under Arizmendiarrieta’s tutelage they were also becoming activists in their own right.

Arizmendiarrieta thought every worker should share in the profits, not just the owners, and he exerted his influence as parish priest to encourage it. “He proposed to the management at Union Cerrajera that they should advance towards a different model of relationship,” Ormaetxea said. “For the sake of social justice, he said they should abandon this paternalistic approach with initiatives financed out of company profits, to which the workers were also, by right, entitled.”

They didn’t listen. When the owners of Unión Cerrajera cut benefits to the workers in 1949, Arizmendiarrieta’s disciples striked with all the rest. “The uninterrupted and progressive social maturation we had been experiencing under Arizmendiarrieta’s guidance led us inexorably to call for change,” he said. “We raised several issues related to worker protection, such as occupational health and safety, holidays, the aid fund and entitlement for manual workers to have an ‘English Saturday,’ i.e. to finish work at midday on Saturday. However, our proposals fell on deaf ears.”

When, in 1954, Unión Cerrajera shareholders announced they would be increasing their share capital, it was the final straw. “We wanted them to use the opportunity to allow the workers—who numbered around 1,200—to participate in the running of the company,” Ormaetxea wrote. “We requested that 20% of the capital increase be distributed in the form of a worker shareholding.”

They were refused.

“What this clearly showed was that any in-depth reform of the company from within was impossible,” Ormaetxea said. “The law could not be transgressed, and the prevailing paternalism contributed to maintaining unjust relationship structures in the company. ‘The son of a laborer must always remain a laborer,’ and ‘the son of an engineer must be an engineer.’”

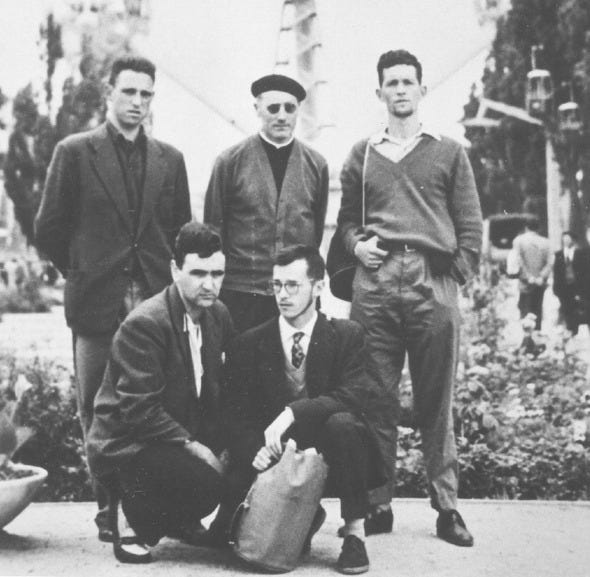

If change couldn’t come from within the system, Arizmendiarrieta said they would have to build a better one. Among the engineers he had selected for education, five of them—Ormaetxea along with Luis Usatorre, Jesús Larrañaga, Alfonso Gorroñogoitia and Javier Ortubay—decided to strike out on their own and start a personal appliance company owned and run by its workers.

Many in Arrasate thought Arizmendiarrieta was a crazy idealist. Breaking with Unión Cerrajera was a huge risk, and what he was asking them to build didn’t yet exist. A company in which the workers were the owners, and even participated in the running of the company? Impossible! When someone stood up in a meeting, blaming the Civil War for their misfortune and lamenting that nothing could be done under the Franco regime, Arizmendiarrieta rebuked him, saying: “We have to do things here with Franco or without him.”

And: “Many people who complain against their destiny should only complain against themselves.”

Arizmendiarrieta and his followers created their own destiny with a loophole: If they couldn’t start their own business, they would buy an existing one, then make it in their own image. They found a company for sale with authorization to “build appliances for domestic use.” This covered gas as well as electricity, which were their forte, allowing them to manufacture home appliances like stoves and car parts.

They didn’t have the money to buy it, but members from the community rose up around them, contributing what they had in hopes that their children might one day be able to work in the company. “We needed around 12 million pesetas, equivalent to about €3.7 million at today’s rates,” Ormaetxea said in 2021. “In less than six months around 115 potential members signed up, each contributing about 90,000 pesetas.”

Ulgor, began.

Early on, the founders agreed that the company’s profit would be divided into three parts: One part would be invested back into the business in the form of buying capital (land, buildings, machinery, etc.), one part would go to the business leader, and one part would go to the workers. Workers would participate in the running of the company by vote.

This was a sharp departure from how Unión Cerrajera operated, which still believed the success of the company came from the superiority of its well-bred shareholders. “People mistakenly believed that this was the result of impeccable management, rather than being the product of political, union, commercial, and economic protectionism.” Ormaetxea said. “That created a mistaken belief that any engineer, economist, or lawyer was capable of running a company. The managers passed their positions on to their children, in the belief that a capacity for entrepreneurship and management was something that was genetically inherited.”

It wasn’t. Arizmendiarriata believed it wasn’t any kind of elite order that made people excel at running businesses, it was education. “We must end the practice of considering workers as under-aged children who always need others to make decisions for them,” he said.

Instead, he empowered them. Arizmendiarrieta’s vocational school trained every worker to become an entrepreneur, not just those at the top. As a result, Ulgor workers knew how the business worked, and were trusted to participate in the running of it. “Everyone is an owner and everyone is an entrepreneur, without discrimination, in good and bad times, contributing with the available capital and the needed work,” Arizmendiarrieta said.

The harder they worked, the more money they made, and the more people they were able to hire. They worked in solidarity, not just for the benefit of themselves but for the benefit of the greater community. It wasn’t easy, to be an Ulgor worker meant pulling one’s weight. “One cannot sit at someone else’s table indefinitely, without ever contributing anything,” Arizmendiarrieta said. “Each person has a benefit from society and one must offer to serve and give to society in kind.”

Workers were given responsibility. For the first time, “our dreams for the future centered on becoming something more than just employees,” Ormaetxea remembered.

Demand for jobs at Ulgor skyrocketed. “[Workers] wanted to get away from the absolute submission they had to endure in traditional companies and find alternatives,” Ormaetxea said. “Within six years the number of cooperative members had swelled to around 1,250, accounting for approximately 10% of the 13,000 jobs in the manufacturing industry in the whole local region [comarca].”

When other factories in the region began losing workers, they demanded Ulgor close their doors to them. “There was no way we could agree,” Ormaetxea said. “We told them, verbatim: ‘The cooperative will respect the open-door principle; if a worker asks for a job and the cooperative can give it to them, then the cooperative must take them on. It is on you who need to ensure that your employees do not leave, by finding ways to make them identify more enthusiastically with the company they work in.’”

The cooperatives were thriving, but it wasn’t enough to create jobs and income and democracies just for a few, they needed to create them for the many. “[Arizmendiarrieta] told us… ‘If you do not extend this business model to other potential projects, you will have fallen into the same trap of self-limitation as other companies from Mondragon,’” Ormaetxea said.

Shortly after Ulgor was founded in 1956, a group of students at Arizmendiarrieta’s vocational school purchased another company, Fagor, that would make dies for industrial processes. “With Fagor, the decisive step was taken for [the vocational school] to become a breeding ground for entrepreneurs who would launch new business initiatives managed only by workers,” Ormaetxea said.

That’s when the Franco administration clapped back, creating a new regulation that excluded cooperative workers from receiving social security benefits. This would have been a blow to workers, rendering them unable to retire, but the founders of both companies quickly pooled their profits to fund a third company: LagunAro would use the profits from both companies to provide retirement benefits for the workers at both.

This was the first collaboration, but it was quickly followed by a second one. If they were going to keep creating new businesses, Arizmendiarrieta said they’d need a way to fund them and ensure their long term success. They created the Caja Laboral Popular in 1959—the bank! Ulgor and Fagor deposited their money into the bank, so did the local community. Within a few years, the bank was earning enough interest to start funding new endeavors and growing existing ones.

With a school that would train new entrepreneurs, a bank that would fund them, and a collection of cooperatives in which workers shared ownership of the company and earned benefits in the process, by 1962 young workers from around the region were applying in the hundreds. Back then, the minimum investment for a new worker-owner was 50,000 pesetas, but they gave around 95,000 on average—around €20,000 euros in 2021, “Which gives some idea of how keen people were to join a new cooperative with all the backing of Ulgor and Fagor,” Ormaetxea said.

They were a success. Within 10 years of opening their first business, the group had founded 36 cooperatives and were earning €18 million in revenues (3 billion pesetas). They had surpassed the Unión Cerrajera as the largest employer in the region, with workers earning better wages and enjoying better worker protections. They were owners of their own companies, participators in the running of them, and active members of the country’s first democracy.

Arrizmendiarrieta didn’t write a manifesto, but he was building a living one. His cooperatist creed established work as the most important thing a human being could do, and economic development as the most important thing humans should work toward.

He wrote that God was able to rest on the seventh day because Man was able to continue the act of creation with Him. “Work is not God’s punishment but instead proof of the trust God gives humans by making them fellow collaborators,” he said in an early publication. “In other words, God makes Man a partner in His own company.”

A better economy and a better world were one in the same, Arizmendiarrieta thought. “Economic development represents human progress and constitutes a true moral duty,” he said.

“Creating employment opportunities is fundamental to the development and wellbeing of nations and towns,” Ormaetxea explained. “It is industry, large and small, that made this land rich and drove its economy throughout the 20th century. Industry created a real economy to replace the rural agrarian economy, and its strength carried construction and services along with it, leading to job creation and enhanced welfare.”

If work and companies create our welfare, we have once again turned against them. A modern Marxism has emerged against the inequalities of capitalism, demanding that our governments solve them. Arizmendierrieta never believed this was the way. “Our beloved democracy may degenerate into a dictatorship through the abuse of power of those at the top,” he said, but just as well “through the renouncement of power of those at the bottom.”

We should not renounce our power under the assumption that any given leader will save us. There was certainly a temptation to do so after Franco died in 1975. As the country’s only living democracy, Mondragon founders were in a place to help the Basque Country and Spain transition away from their dictatorship, but Arizmendierrieta said this was not the solution.

“He exhorted those closest to him not to get involved in politics,” Ormaetxea said. “He said to us: ‘Stay out of politics. It will divide you.”

Politics continue to divide us, but our needs still unite us. “If your house has burned down and you need someone to solve the mess, you don’t start weighing up whether this person is a nationalist and this other person is a republican and another is whatever,” Ormaetxea said. “You just try to ensure that the necessary work gets done.”

The work that needs to get done is the same: It is still through our work that our companies become more wealthy. It is still through the company's generation of profits that we create a more prosperous society. It is still the company that builds the things we need for society—food, energy, buildings, bridges. We need to build more companies that create more of the things we need for society, so we can create more jobs, so everyone in the world has access to jobs and money and prosperity.

If we have become ambivalent about that it is only because we have grown too comfortable with what the capitalist system has provided for us and we can no longer remember what it was like to go without it.

When Arizmendiarrieta first set out to improve economic inequality in the 1940s, 95% of Arrasate-Mondragón attended Catholic mass—their community was poor and lived very austere lives. But by the time the founders of those first Mondragon cooperatives began retiring, only 5% of the community attended mass and they were well off and comfortable. They weren’t as urgent in their need to fix the inequalities in the world, and they were no longer exposed to them every day.

“The women and men joining the cooperative movement today live in more reasonable comfort and are largely university-educated. They have not suffered the same economic precariousness, the same hardships or the same prejudices that were so firmly engraved in the minds of the first cooperators.” Ormaetxea said. “We should not, therefore, be surprised that the assimilation of other models of societal relations does not spark the same tension or intellectual disagreement that it would have unleashed in the early decades.”

Even before his death, Arizmendierrieta felt the tides turning. “Never has there been so much talk as in recent years of humanity, of the common good, of the class interest, of the good of humanity,” he said. “And yet we have arrived at a social situation in which caprice and ambition, pride and arrogance, selfishness and the cruelty of the strong have never been more commonplace in the world, to the detriment of the true interests of the masses, of men [and women], of humanity. This is what we have come to.”

It is within our agency to fix this. With our work, with our companies. We don’t even need to create a world of cooperatives to do it.

“The best is the enemy of the good,” Ormaetxea said. “While it would be preferable for them to be cooperatives, if they are creating employment, then that in itself is a good thing. The important thing is not to create new forms of company, but to create new companies. Then, within the company, you need to be fair.”

Arizmendiarrieta believed we needed to grow the economy first and foremost, as much as we can. “We can not be pleased,” he said, “with any paradise that is walled in.”

“In reality we are all in solidarity; it is not necessary to belong to the same cooperative enterprise to be so,” Arizmendierrieta said. “The economics is structured more and more based on a growing division of work. Everything is done by everyone. The agricultural, industrial, and service sectors are members of a community, of one same economic process. It is a matter of becoming aware of this basic solidarity.”

But we should share the wealth more equitably as we do so. “Any business person should find in it their motivation to act socially,” Ormaetxea said.

This is our continued maxim.

Arizmendiarrieta’s manifesto is not done, and perhaps that’s why it could never be penned down on paper. “We should not live cooperativism as if what is accepted and decided at a given moment were something unchangeable,” he said. “Rather, we should admit it as a process of experience in which it is possible and may be necessary to adapt as many modifications as can contribute to cooperativism.”

We are still evolving, and there will always be more problems to solve. Even as they were building successful cooperatives and scaling them throughout the Basque Region, detractors continued to say it wasn’t enough. Arizmendiarrieta had no patience for that kind of mindset.

“Perhaps at some moment, those who thought that the cooperative solution would resolve everything (which each one may imagine) can take note of the unreality of such assumptions so as to avoid unnecessary dissatisfaction,” Arizmendiarrieta said. “We do not apologize for shortcomings that may be pointed out to us. We are on the way.”

And we have to keep going.

“The problem now is not to place ourselves in the conditions of avoiding work, but instead of making work a service, and, to a large extent, a source of honest satisfaction,” Arizmendiarrieta said. “Work can and should be humanized.”

In his memoir, Ormaetxea recommended a practical solution for today’s cooperatists: Don’t start with what the world needs, but with what your local community needs. Make an analysis, detect the problems facing economic development, then make a plan to fix them over the next 10 years through your work and your business—even better if you can do it through a cooperative or an employee-owned business. Evolve your plan over time according to the needs of your community.

Just like Marx’s ideas, we shouldn’t stick with the old ones in hopes that they’ll save us, but evolve them into new and better ones as we figure out what works. “To live is to walk ahead without retreating,” Arizmendiarrieta said. “In each stage of life, human beings encounter new difficulties and problems, which they can not avoid by retreating but must resolve them or die under their weight.”

Karl Marx’s words, proliferated through pamphlets and books and recirculated through the masses for decade after decade have had a lasting impact on the populace and are still resurfaced today, while José María Arizmendiarrieta was quietly building something better: A working model, a collection of 92 cooperatives benefitting 70,500 workers, earning €11 billion in revenue and functioning like a democratically run city-state. Yet it remains a local secret, not written down but lived.

We can’t keep it secret anymore. We need to establish Arizmendiarrieta’s manifesto for the masses, and write it down for the next generations.

We need to create more worker-owned businesses and cooperatives, to create more economic opportunity globally, and to proliferate and evolve his ideas from here.

When Father José María Arizmendiarrieta died in 1976 he left a legacy, but also a responsibility: “The world has not been given to us simply to contemplate it,” he said, “but to transform it.”

Thank you for reading,

P.S. This essay is a continuation of my capitalism series, and my exploration of Mondragon Corporation, establishing ways we can evolve capitalism to work better for more people. If you enjoyed this essay, please consider supporting my work as a paid subscriber.

And thank you for sharing it! That’s how I meet new subscribers and earn a living from my work.

I really like the practical thinking. Solving a problem by doing. If that plan fails then try something different,. Change the process not the goal. The best part is not waiting for salvation. Others may or may not help, you need to start working on fixing the problem yourself, action motivates others. Excellent article, thank you.

So many great quotes of wisdom, thanks for putting in the time and effort to write about Mondragon.

The need for a single source of knowledge about Mondragon, like a manifesto, is evident. I hope you are working to create this. Could be a great service to all of humanity.

Just from your two brief articles you’ve written about Mondragon, I have been inspired to take action towards cooperativism in my lifetime!