Mondragon as the new City-State

This cooperative could be its own country.

Mondragon is the largest group of worker cooperatives in the world.

With 92 cooperatives in the industrial, financial, retail, and educational sectors, the group earned €11 billion in revenue last year with more than 70,500 workers.

Each of those cooperatives are owned and democratically run by their workers, who vote their leadership into office and share in the profits when their cooperatives do well.

In fact, Mondragon works a lot like a federated nation-state made up of smaller city-states. Perhaps that’s why science fiction authors like Ursula Le Guin, Kim Stanley Robinson, and Cory Doctorow have all used the corporation as a model for the utopian nations in their books.

Could we eventually create a capitalist paradise where democratically run companies use their profits for the good of their worker citizens? Could that even replace our existing governments?

“Years ago our founders had this kind of vision—to have a ‘world cooperative economy,’” Germán Lorenzo, who works in global public affairs, told me when I visited Mondragon’s headquarters. “An ideal utopia would be a full cooperative world—people own the means of production, there’s a fair distribution of wealth.”

In 1956, one Catholic priest began building it—starting with the Basque Country.

Father José María Arizmendiarrieta was just 26 years old when he was sent to the parish of Arrasate-Mondragón for his first (and what would be only) assignment in 1941. It was just after the Spanish Civil War and the country was under the control of the nationalist dictator Franco. Arrasate was destitute with high levels of unemployment and economic hardship. People needed money, which meant they needed jobs.

So Arizmendiarrieta created them.

What started as one employee-owned business became a network of them as his followers kept starting new businesses and adding them to the network. They worked like an incubator, founding a university that would train entrepreneurs, then a bank that would fund their visions. They built manufacturing companies that would give them high-paying jobs, a housing company as they grew, and a preschool where their children could get an education while they worked.

Each new startup arose out of the needs of the community, and each one was owned by its workers. Eventually, they bought up an entire mountain and expanded to neighboring cities. As they grew and joined the EU they became more competitive worldwide, founding tech companies and R&D facilities. Today, three out of every 10 cars use Mondragon components, 90% of the world’s aircraft use their technology solutions, 60% of the world’s trains are built using their machines, and more than a third of Europe’s solar panels are made using their technology. You can find Mondragon brands in Audi cars and Tour de France bikes, technologically advanced hospitals and electric vehicle charging stations, green energy power solutions and water management facilities.

Mondragon has spread throughout the seven cities of the Alto Deba region. No matter what you do for work here you are probably working for a cooperative, and no matter what you spend money on you’re also supporting one. You might work as a computer engineer for a tech cooperative, deposit your paycheck into a cooperative bank, and spend it at a cooperative grocery store or on cooperative-built cars. Your home might be powered by a cooperative-run energy company, your children might attend a cooperative school or university, and your parents might live in a cooperative retirement community.

As they say in the Basque Country: “Life is cooperatized here.”

Over time, these cooperatives have federated together as Mondragon Corporation. Each cooperative is part of a larger division, and each division is part of the larger federated group. A cooperative that makes hubcaps, for example, might be part of the larger auto parts division, which is part of the larger Mondragon Corporation.

The profits generated by each cooperative are put to work for the benefit of the greater whole. Each cooperative pools 14-40% of their gross profits with their division (depending on the division), and gives another 14% to Mondragon Corporation. The rest are invested back in the cooperative (60% of net profits), distributed among their employees (30% of net profits), and donated to social organizations in their communities (10% of net profits).

The bulk of cooperative profits stay with the cooperative and its workers, but there are benefits to being part of the larger organizations. Divisions use surplus profits to account for losses within the group, and the Corporation uses half its revenue to invest in their businesses (and start new ones) and the other half to provide social services for workers.

When the Spanish government issued a regulation in 1958 that cooperative owners would no longer qualify for the country’s social security program, Mondragon created its own. They founded Lagun Aro, a social welfare arm that provides pensions for workers and their families, as well as disability services when they can’t work. Eventually, it created its own healthcare service, providing medical care for workers and their families.

When there was a massive downturn in the economy in the 1980s, 20 cooperatives were forced to close their doors, but other cooperatives in the portfolio were thriving so Mondragon just transferred people from one cooperative to another, paying for the education each worker needed to fulfill their new roles. On the whole, jobs rose.

If workers can’t be relocated, Lagun Aro will pay a percentage of their salary for up to 24 months—though Lorenzo tells me this has never happened. The most recent cooperative to shut its doors was an appliance company that once had revenues of €1.3 billion. When Fagor shuttered 10 years ago, Mondragon had to relocate close to 2,000 employees from one cooperative to another, and they did.

“In a crisis situation, where other companies send people home and they waste their time watching videos and smoking, what we do is train them inside, and retrain the force,” Lorenzo says. “People keep working. That's important.”

As their founder used to say, “There are no useless people, only underutilized ones.”

The area has become much wealthier as a result. “A large number of cooperative jobs are industrial so their income level is high,” cooperative communications officer Ander Etxeberria Otadui explained in a video series about the organization. “Studies that analyzed Alto Deba at the beginning of the 1970s already showed that the per capita income was significantly higher than average for the province. Today, it has one of the highest average incomes in the Basque country. Plus it’s more equal.”

As a rule, the highest-paid workers at Mondragon cooperatives earn only six times more than the lowest-paid workers. A worker’s position on the payscale, between levels one and six, also determines their share of the profit-sharing pool. Lorenzo estimates that the president of Mondragon is the highest-paid position with a salary of around €200,000. Managers and directors earn between €80,000 and €120,000.

Workers buy into their cooperative when they become employees, investing up to €16,000 into a “personal capital account.” They pay 30% of that investment upfront, with the remainder taken out of their paychecks over following 2 to 7 years. After two years with the organization, workers can decide to become “members” and start earning interest on their investment, historically at a rate of 7.5% annually. If the cooperative does well, they might earn much more than that. Workers can pull this money out of their accounts when they leave the cooperative or retire.

“It’s a fact that the cooperative system uses wealth in a much more fair way,” Lorenzo says. “Our Gini Coefficient is similar to Sweden or Norway or Denmark, it’s very low. That means the cooperative system, in fact, is a much better way than the capital system for the world.1”

When I asked, at an informational lecture, if people ever leave for better pay, Lorenzo said few do. When another asked how they keep motivation high throughout employees' lengthy careers, Lorenzo recanted: “Your question is asked from the perspective of somebody who is working for somebody else. Here you are working for yourself. We have a higher level of self-consciousness.”

If workers want to try something different they have the autonomy to move elsewhere. Lorenzo started his career in global purchasing and imports for Eroski, Mondragon’s retail brand. Eventually, he moved to Hong Kong where he spent four years working in business development for Intergroup Far East, Mondragon’s international sourcing office. When he returned to Spain, Lorenzo headed up the Asia-Pacific unit for Mondragon Corporation. Craving a change of pace, he then moved to Mondragon University’s business school where he spent a couple of years helping with their entrepreneurship program. Now, he’s working in global public affairs and communications, developing Mondragon’s corporate diplomacy and internal communications.

“I can’t say they didn’t give me room to move,” Lorenzo says. “My wife says they gave me too much.”

Every cooperative in Mondragon’s portfolio is an essential business—these are manufacturing companies, energy companies, agricultural companies, medical equipment companies, banks. They grow our food and power our cities and build our transportation systems. Their research and development groups invent machines and robotics that improve our world. There are no fast fashion or telemarketing companies in their portfolio. This cooperative of cooperatives is run by workers who directly build the things society needs while directly benefiting their communities with the profits they earn making them. They are self-governing locally even as they compete globally, with plants around the world and products and services sold in 150 countries.

The result is that Mondragon has created something of a self-sustaining government—and a pretty good one, I might add. Each cooperative functions like its own democracy, with workers functioning more like citizens. Cooperatives average 250 workers and larger ones often split off into separate cooperatives with separate democracies.

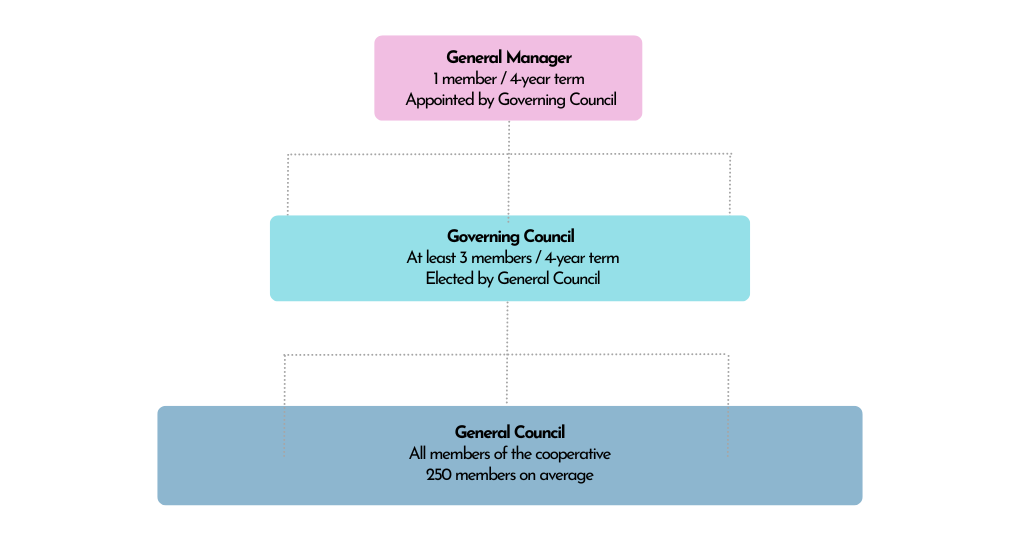

Every year, workers (internally called the “General Assembly”) meet to review prior years’ management, decide how to allocate profits or losses, and approve annual accounts. They vote their board of directors into office (called the “Governing Council”) who, in turn, vote their CEOs into office (called “General Managers”). General Managers hire their own executive team and make periodic reports to the Governing Council who can confer or revoke their powers as necessary. Positions of leadership serve a renewable four-year term and will be removed from office if they aren’t doing a good job.

The parent company works similarly: “Congress” is an assembly of representatives from every cooperative. They vote for the “Standing Committee,” who appoints the “President,” the head of Mondragon.

Each cooperative pays for workers’ education at Mondragon University, itself a cooperative in the Mondragon network. There’s even a bootcamp program for General Managers—a sort of entrepreneurial “CEO school”—where executives have the support they need to run financially successful companies, and have the opportunity to learn from executives at other cooperatives who have done so.

Together, they’ve even formed a constitution: The “Rules of Congress” outlines the articles of their organization and includes the corporation’s strategic plan—or “socio-business policy”—which is prepared and voted on every four years. During the time of my visit, Congress was getting ready to meet about the organization's plans for 2025 to 2028. (Reminiscent of my essay: “We should vote for plans, not politicians.”)

Each democratically-run organization is supported by the larger democratically-run Mondragon. Workers at Mondragon cooperatives are guaranteed a job and an income. They are taken care of when they can’t work, provided with universal healthcare if they get sick, receive universal education that trains them for any job, and are provided a pension when they retire. There is no unemployment, no poverty. No one is sitting around collecting handouts from everyone else, they are all actively working and contributing to the system.

And unlike governments, the cooperative provides all of these things with profits, not by taxing income.

Workers at Mondragon still get income taxes taken out of their paychecks, and cooperatives still pay corporate taxes, but at a much lower rate than traditional companies. And those tax dollars go to the Basque Country, itself an autonomous region that uses them (plus VAT taxes on goods and services) to fund things the corporation can’t: like infrastructure and elementary education.

Mondragon’s democracy was, in many ways, a precursor to the ones that would eventually come to Spain. The organization was in business for 19 years by the time Franco died in 1975 and Spain started transitioning to a democracy. The Basque Country was established as an autonomous region in 1979 and they elected their first parliament in 1980.

As the largest employer in the region, Mondragon and the Basque Country evolved together, and they remain very intertwined. “When they try to change the co-op law, they call us,” Lorenzo says. And when Mondragon wants to change cooperative law, they call the Basque Country.

To this day, the two work reciprocally for the benefit of the region. Workers can now choose between Mondragon or Basque healthcare, and they have access to Spanish social security programs along with their Mondragon pensions. Lagun Aro fluctuates to fill in the gaps of government as needed, and the government fluctuates to supply the needs of the region. The Basque government also contributes a quota (called a “cupo”) to the Spanish government to fund defense, foreign affairs, and larger national projects that benefit the whole country.

In this way, Mondragon acts as a self-governing city-state within a larger state and nation. Each individual cooperative has the most authority over workers’ lives, even as layers of Basque and Spanish governments provide larger, but more lightweight methods of governance for the greater whole. The structure works a lot like the one I outline in my essay: “Decouple federal government from nation-states.”

“We work at three levels: With the Basque Government, with the Spanish Government, and with the European Government,” Lorenzo says. “Our aims are global, we want to create wealth, jobs, and develop a better strategy. Every government loves that idea.”

If the model is a good one, detractors say it can’t be replicated outside of the Basque Country, and there’s some truth to that. Once employees are here they tend to be lifers, but getting them here has proved a real challenge. Lorenzo says they hire about 30% of their workforce from Mondragon University, but they need to hire more engineers than they can find in the Basque Country, and that means recruiting abroad.

This is logistically challenging, but also culturally. “In the US, I have to buy a million-dollar house and $100,000 car, and have 80,000 products,” Lorenzo says. “The capitalist world is built on selfishness, individualism, being number one. We can’t attract the kind of hard talent that wants to make money and be number one.”

Living expenses are much lower in the Basque Country than they are in the US, but so are salaries and that can be a tough sell. Dreams of becoming a billionaire are nonexistent. When I published an essay about employee ownership, one person commented: “Why the hell should anybody still start a company and want to become an entrepreneur when he needs to give stocks to every employee he hires? This is completely stupid. If you want to become rich, become an entrepreneur.”

Mondragon is a different mindset. “We feel that our collective ‘us’ is more important than ‘me,’ but they are more independent, individualistic people,” Lorenzo says. “So it takes some time to really convince people that this system is worthwhile. They see sometimes that we are a compromise for a full life, so we have to think in new ways, adapt our system.”

In Europe, cooperatives like Mondragon grew up alongside consumer co-ops like John Lewis & Partners in the UK. The Alta Deba region of the Basque Country isn’t so different from the Emilia Romagna region in Italy where cooperatives like SACMI and Manutencoop are highly networked with one another and cooperatives make up a third of the region’s GDP. In Brazil, Unimed recently became the largest worker cooperative in the world by revenue (Mondragon is second), providing an alternative to capital-based health systems.

While, in most of the world, capitalism grew up alongside the Rockefellers and the Carnegies of the world, cooperatives in Europe and South America were creating a much better form of it, but it’s a stark contrast. Try convincing the Jeff Bezos’ of the world to start a cooperative. Conversely, try convincing a Mondragon manager to keep the stock for themselves and become a Jeff Bezos. The two models come from two very different worlds.

“I think it is possible to replicate, but it requires people who believe in the model and know how to replicate it,” Lorenzo says. “Before he opened the first co-op, [Arizmendiarrieta] had spent nearly 15 years preaching. He was educating, he was creating mindsets. It’s not a copy-and-paste issue, I don’t think it’s that easy.”

If it’s education we need, Lorenzo admits Mondragon has fallen short. “We’ve been very good at doing, but not very good at telling these last 50 years. That’s why I’m sure your article will give us a good position.”

Even as a journalist, information on the company has not been readily available. The books I read on the subject are only available at company headquarters, the biography of its founder is only in Spanish. Knowledge about the model is limited to academic journals, a sparse Wikipedia page, and a spattering of mainstream articles that extol the benefits of cooperatives without diving deep enough to explain why they’re interesting. After emailing the corporation for a year, I was only granted an interview if I could attend one of the company’s in-person media days which are hosted once a month. I had to buy a plane ticket, rent a car, drive six hours from the Barcelona airport, and rent a hotel nearby to get a meeting—a large expense for an independent journalist.

It makes sense—cooperatives are businesses first and cooperatives second. They have to compete with other companies on the market, and win, to make a profit. Only then can they use that profit more equitably. “We bought the chairs in this room from a company that’s a cooperative,” Lorenzo illustrated, “but we got them because they were the best price and quality, not because they were from a cooperative.”

Mondragon can’t afford to spend all their time proselytizing. What founders do come to study the model might put it into practice, but if they only create one cooperative that benefits 100 workers, Lorenzo says they miss the point. They need to create a network of them to fund new startups, create new jobs, provide social services, and transfer workers between companies. It is the combination of cooperatives that makes the whole thing self-sustaining, not the individual ones.

There are very few of those. As of 2017, there were only 11.1 million worker-owners globally, out of 3.39 billion total workers—that’s only 0.33% of the working population, and it’s not growing.2 Employee ownership is rare, democratically-run cooperatives are rarer still, and a whole network of them? Mondragon and Unimed are really the only ones.

Because of this, Lorenzo thinks we won’t create a world of cooperatives as the founders once imagined. “I think this is fiction because at the end of the day, there are forces in the world that are difficult to scale up.”

If cooperatives are still a niche movement, the movement to make capitalism work better for more people is massive.

As is well documented in Thomas Piketty’s work, inequality has been on the rise since the 1970s when wealth taxes were skewered and executives started getting paid in stocks. Those who owned capital (such as real estate, stocks, and bonds), got much richer, and because they got much richer, they bought more capital. Return on capital exceeds the rate of economic growth, meaning those with significant wealth saw their fortunes grow faster than the economy, the rest didn’t.

A widening gulf now threatens to become much wider and the result is outrage. When the rich can afford mega-yachts and a well-paid software engineer can’t afford a house, we see a rise in the same “eat the rich” mentality that once cost Marie Antoinette her head. In the US, only 40% of those ages 18 to 29 view capitalism positively. Democrats think better of socialism than capitalism, 67% of young Brits do too. According to a Wiley’s worldwide survey, most countries are now anti-capitalist. Their top reasons why are all related to inequality.

The most popular proposed solution is a wealth tax, but that could be enacted by one president only to be thrown out by the next one (or used to fund military endeavors rather than social ones). More extreme options involve eradicating capitalism altogether by returning to subsistence farming and bartering or giving the government control of the economy—we’ve tried both options and neither fared better for humanity than our current capitalist system.

One option, however, has.

Mondragon provides us with a successful, working model. It’s not throwing out capitalism, it’s creating a better form of it. It is still private individuals who own capital, but more of us become owners. Companies are still getting wealthy, but that wealth is put to better use. Rather than create a few rich people only to tax them on the back end, we allow everyone to get richer on the front end. We don’t get there through revolution, just evolution. Instead of descending into “late capitalism” we start building “mature capitalism.”

We need to channel all of that anti-capitalist sentiment into a better capitalist solution, and we can start with what is already working. Most worker cooperatives are concentrated in Asia (8,573,775 worker-owners) and Europe (1,554,687 worker-owners) where cooperatives are a more widely accepted business model and offer a democratic solution where there are less democratic governments—we should build more of those. Though there are significantly fewer in the Americas (982,285) and Africa (37,836), recent policy changes have incentivized employee ownership in the US, Canada, and the UK, as well as transferred ownership to 307,000 workers at 118 firms in South Africa—we should build more of those too.

Around the world, we need founders to start new cooperatives and sell existing companies to employees—we need our governments to incentivize both options, and it’s in their best interest to do so! If we can create more employee-owned companies, maybe we can slowly start edging out the shareholder-owned ones. If we can create a critical mass of them, maybe we can even start federating them together as Mondragon once did. If we can create more democratically-run companies, maybe then we won’t need our countries as much.

With Mondragon-like clusters of profitable, democratically-run businesses, what we currently call government could be sufficiently stripped down to infrastructure and militaristic support.

Anarchist, socialist, and capitalist thinkers alike have gotten behind this solution, with sci-fi authors imagining a world of cooperative city-states. “It’s funny that they use our ideas at all kinds of levels,” Lorenzo says. “Socialist, anarchist, capitalist—at the end our aims are very legitimate. We want to increase wealth, create jobs, and try to develop, in a way, a better world.”

I still think we could get there—that we could create a world of cooperatives. It is at least one of our options. The future is long and capitalism is still new. It is still transforming into something better and evolving into what it will become. Humans are demanding a fix to inequality and companies like Mondragon are providing a successful blueprint we can follow.

In a 2021 book about the founding of Mondragon, authors Armin Isasti and Isabel Uribe thought Arizmendiarrieta’s vision wasn’t yet done: “We need to imagine the future, consider alternatives, form new collectives, and be able to see beyond ourselves. We need to return to utopian thinking; we need people who have the courage to be utopians as José María Arizmendiarrieta was. Far from being satisfied with completing Arizmedi’s utopia, let us continue to yearn after a world in which imagination and hope are alive and active.”

Arizmendiarrieta himself believed that vision was the first step. “Most of what has been achieved through conscious and responsible human effort has been, in first instance, a beautiful ideal,” he said. “And only that.”

So long as we can imagine that beautiful ideal, maybe we can even create it.

This article is part of my book We Should Own The Economy, which I am researching in public.

Thank you for being here,

Lorenzo is referring to the Gini coefficient for the Basque Country and Guipuzkoa province specifically, of which Mondragon is a large part.

Many articles use stats about cooperatives as a whole to paint a picture of a growing movement, but those numbers include consumer and producer cooperatives which are not the same thing. You might be a “member” of your grocery store or outdoor retailer, for example, but the dividends you receive give you a discount on goods, not stock and profit sharing in the company. Worker cooperatives are a much smaller portion of the pie—on the World Cooperative Monitor’s list of the top 300 cooperatives by revenue, only five were worker cooperatives.

Brilliant article! Your outlines of the cooperative’s structure and implications for a fairer economic system were clear and persuasive. Your writing makes a strong case for the potential of cooperatives to transform our approach to capitalism, leaving me with much to think about...as ever.

Great article. I generally am not big on utopian ideas, but this article does get me thinking about alternate versions of capitalism that preserve almost all the benefits of capitalism while reducing some of the more negative effects.

I can definitely see how the model might have difficulty recruiting highly-skilled labor and top-quality managers. With presumably lower salaries and the need to “buy in” with a significant amount of cash, I think this would be a competitive disadvantage. But it does seem great for lower- and middle -skilled jobs.

I do wish that there were more ESOPs and cooperatives. Perhaps an elimination of corporate taxes for them would be a reasonable incentive to get them going. With proper publicity, this might be something that both the Left and Right can agree on.