We don't need to "degrow" the economy

To save the environment.

The economy is really important—having a good economy means we have good jobs and we’re making good money. But, in the future, we will either need the economy to grow bigger or shrink smaller, and this is a debate that continues to wage among futurists.

The growth argument goes like this:

The bigger our economy is, the better it is for humanity. Because the more resources (energy) we use, the more we will invent things that help humanity. But we’re not using as many resources (energy) as we used to so we’re not inventing things that will help humanity. And if our population eventually starts decreasing as it’s predicted to do then we’ll use even less energy and invent even fewer things and have less jobs. So humans will stagnate and indeed we already are.

Proponents of this angle include:

J. Storrs Hall’s Where’s My Flying Car

The Works in Progress Newsletter’s “Degrowth and the monkey’s paw”

The degrowth argument goes like this:

The bigger our economy is, the worse it is for humanity. Because we’re just using up all of the resources (energy) on the earth, and we’re polluting the earth as we turn those resources (and energy) into things we don’t need, and then we’re polluting it even more as we throw it all away into big piles that we can never get rid of. And the overconsumption of the rich countries is really negatively affecting the poorer countries so maybe it would be in our best interest to stop consuming so much and let the economy stagnate a bit.

Proponents of this angle include:

The reality

In my mind, there’s a gap between these two angles. The growth argument assumes that a growing economy = growing innovation/progress. The degrowth argument assumes that a growing economy = growing overconsumption/wastefulness. But “the economy” includes a lot of activities, some of which are innovative and progressive and some of which are overconsumptive and harmful. So I wanted to look at what our current economy is producing so we can analyze how much of it is good for humans and how much of it is not.

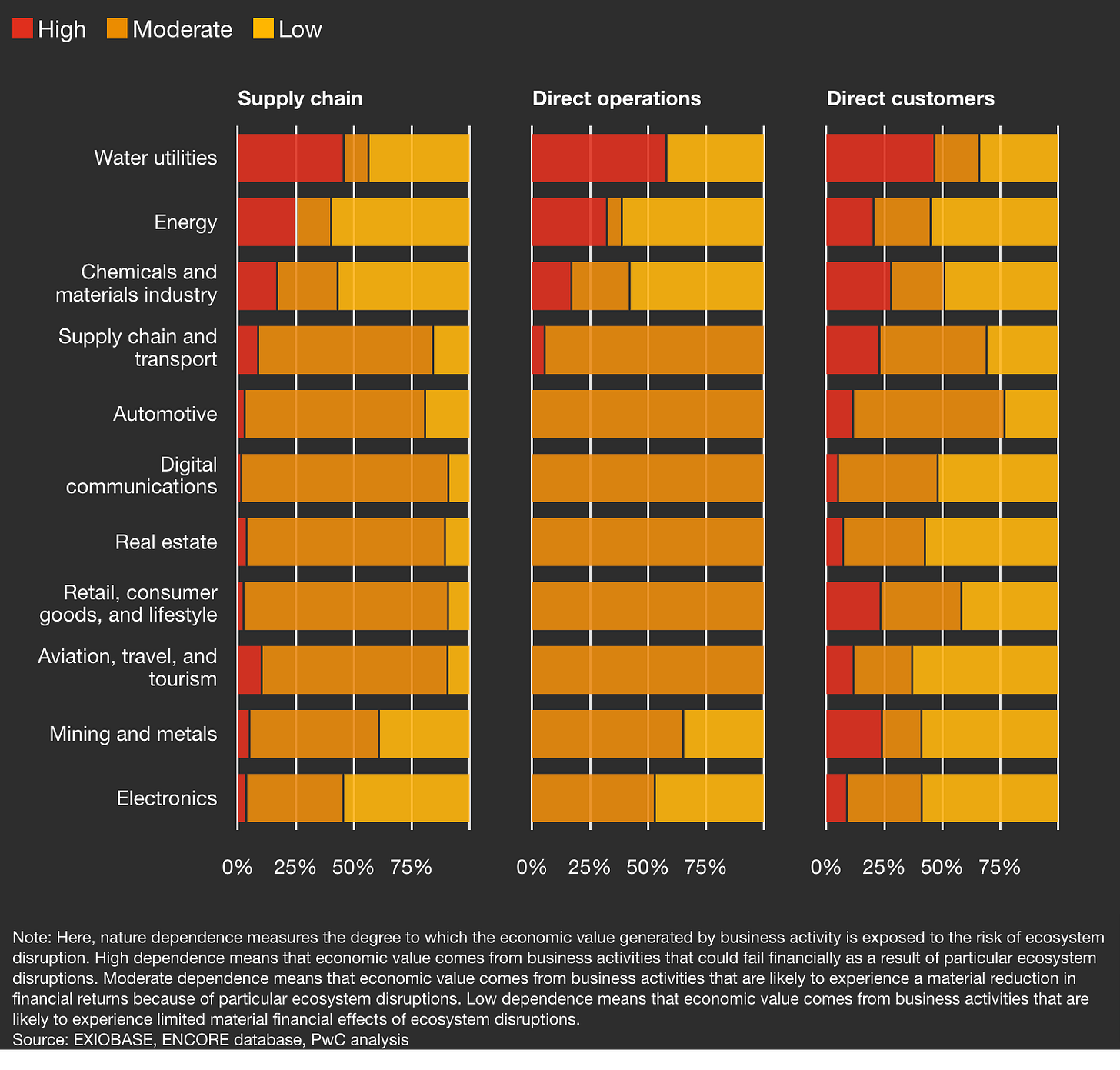

The global economy is currently measured by the gross domestic product (GDP)—the total monetary value of goods and services produced by the world in a given year. As of 2023, the global GDP is worth $105 trillion, and PwC estimates that about 55% of that—$58 trillion—is moderately or highly dependent on nature.

The five industries that are most dependent on nature derive 100% of their economic value from natural resources.

It makes sense that our most environmentally dependent activities are growing our food and constructing our houses and buildings—those are our most essential needs and they require resources from the earth to do. But though these industries are environmentally intensive, they only make up a small portion of our global economy. As PwC says, “Together, the five industries in this group produce more than $13 trillion of economic value—12% of global GDP.”

The next 11 most environmentally intensive industries derive at least 35% of their economic value from natural resources:

And there are whole industries that hardly use any natural resources at all:

This is where things start getting interesting. Water and energy, for example, are next up on the list but only half of their value is moderately to highly dependant on environmental resources. The other half requires few resources from the earth at all—how does that make sense? Shouldn’t the value of water make up 100% of the value of the water industry?? Isn’t the value of the energy industry, the energy we get??

As Jonathan Haskel points out in his book Capitalism Without Capital, the value of the economy comes from two kinds of assets: tangible assets (goods that had to be physically made and thus required resources from the earth) and intangible assets (goods that are not physically made and thus do not require resources from the earth). Companies usually have both tangible assets (things like buildings and roads and construction) and intangible assets (things like knowledge and software and brand value).

Over time, intangible assets have become much more valuable than tangible assets. A university, for example, might have tangible assets like buildings, dorm rooms, and landscaping—and environmental resources are needed to make those physical things—but it isn’t the buildings that make a school valuable. That comes from intangible assets like a school’s reputation, the quality of teachers they have, the knowledge and resources they have available for students, and networking opportunities available to them. And those require few, if any, environmental resources to provide!

This is true in nearly every industry, including ones that might seem incredibly environmentally dependent: Grocery stores and hotels might have a lot of tangible assets—like buildings, produce, and water. But it’s their intangible assets—their reputation, branding, marketing, checkout software, delivery systems—that make one grocery store or hotel more valuable than the next one. Whole Foods or Hyatt Hotels are much more valuable than other grocery stores and hotel chains and it’s not because they have nicer buildings or use more resources from the earth.

As Haskel points out, gyms are about the same today as they were 40 years ago: weights, cardio machines, mirrors, etc. But gyms today spend much more money on intangible assets like management software, booking software, classes for members, and advertising campaigns. “Gym businesses are still quite heavy users of assets that are physical. But compared to their counterparts four decades ago, they have far more assets that you cannot touch.”

It’s in a company’s best interest to invest in intangible assets. That’s because tangible assets are risky—they can be adversely affected by geopolitical movements (like China threatening Taiwan’s microchip industry) as well as natural disasters. Maybe that’s why public companies have invested a larger percentage in intangible assets over time. Because public companies have to report their tangible vs. intangible assets, we can look at the S&P 500 (the value of the top 500 performing companies in the United States) and see how they have progressively invested more in intangible assets over time:

We can also see this effect play out globally. In 2020, Jonathan Knowles did an analysis of the top 10,000 public companies in the world and discovered that 70% of their value came from intangible goods.

Not only are companies getting most of their value from intangible assets, but we now also have entire industries that use very few environmental resources at all. You might have noticed from the above charts that information technology derives nearly all of its value from intangible assets. That’s because a tech company like Spotify might have buildings for its employees and server centers to host its data, and it might use energy to support both of those things, but it is the unlimited access to artists that makes the company valuable, not its HQ or server buildings.

As companies derive more of their value from intangible assets, more of our jobs have become “intangible” jobs. As the Bureau of Labor Statistics points out: “For decades, economists have observed that an increasing proportion of the employed population in the United States has been working in the services sector and thus not involved in the production of tangible goods such as food, clothing, houses, and automobiles.”

And consumers are spending more of their money on intangible services. “This change is also apparent in consumer expenditures data, with consumers allocating an increasing share of total expenditures to services and a decreasing share to commodities. This change has been observed over the last several decades.”

So many arguments against overconsumption use consumer spending data to prove their point. But “consumer spending” includes both physical and non-physical goods—we can’t lump that data together. A consumer might purchase physical goods like a car, a sofa, clothing, a flight from one place to another—and those things all require resources from the environment to make. But a consumer also purchases intangible goods like wifi access, a Spotify account, a massage, a therapy session, a ticket to a stand-up comedian, a newsletter subscription. Those economic activities are still highly valuable but they require very few environmental resources to produce.

Even our most environmentally intensive industries are becoming much less so. For example: we might assume that the more people there are in the world, the more food we will consume and thus the more land we will need. But we are using land much more efficiently! According to Haskel, between 1961 and 2009 the world population rose from 3 billion to 6.8 billion (an increase of 127%) and the world went from producing $746 billion worth of agricultural output to $2.26 trillion (an increase of 203%). But while we produced more food for more people, we actually used about the same amount of land: We went from 4.46 billion hectares under cultivation to 4.89 billion (an increase of only 10%). All because we figured out how to make that physical asset (land) more productive.

Yes, 55% of our economy is still moderately or highly dependent on the environment, and we can and should work to decrease that: We can use less land to produce more food. We can significantly reduce meat production (since 77% of agricultural land is used for meat and poultry). We can swap nonrenewable energy sources (like fossil fuels) for renewable ones (like sun and wind energy). We can outlaw single-use plastics, maybe even consumer plastics altogether. We can make retail companies responsible for the entire lifecycle of their product and charge them for the number of years their products will live in the secondary market, and the amount of time it will take to break down in a landfill.

But 45% of our economy has little, if any, impact on the environment and we can work to increase that. We can incentivize and encourage second-hand retail markets so that there is a greater demand for used and recycled products. We can invest in public transportation instead of private transportation. We can retrofit existing buildings instead of building new ones. We can invest in scientific advancement and technological progress. We can spend our money on experiences and ART!!!!!! And all of these things have a lot of economic value even as they use very few environmental resources.

“The economy” is important because it’s how we make money—that’s why we have jobs and the ability to support our families, and yes, the ability to make scientific advances and technological progress. But we don’t need the whole thing to “grow” or “degrow.” Rather, we need to decrease the economy’s dependence on the environment, and we can do that even as we grow the overall economy—if we need to.

But I’ve only addressed the degrowth argument so far, and I still want to know more about the growth argument. What percent of our economy is contributing toward human progress? And how much do we need that part of the economy to grow (or not grow) to support humanity’s needs? That is the subject of my next essay.

In the meantime, I’d love to know your thoughts. Join us in the literary salon for further discourse on degrowth.👇🏻

Thank you so much for reading!

Marginalia

Here are some additional notes from the margins of my research: