How we achieve the borderless future of Terra Ignota

On Ada Palmer’s utopian sci-fi series and an exploration of how we might bring it to life.

This essay is by me,

, for CITY STATE, a collection of seven writers exploring autonomous governance. You can support the project by collecting the digital or print edition here 👇🏻It’s the year 2131 and flying cars can circle the globe in four hours. When anyone can live in Spain, work in New Zealand, and attend an afternoon meeting in Japan, the nation-state becomes irrelevant. Why would anyone pledge allegiance to the patch of dirt they were born on?

That’s exactly what Americans are asking themselves when their government enters yet another war they don’t want. The heads of the three transit groups, “which can evacuate members from continent to continent to evade a draft as easily as watch a sports match,” call a press conference.

“This so-called nation dares, not merely to ask, but to compel these free people to send their children to fight and die for a group of men they do not call leaders, against a foe they do not call enemy, over a patch of ground they have never called home,” they orate from the dais. “Friends, an America who would impose these orders is no longer the champion of liberty its founders set out to create.”

The European Union is the first to offer floating citizenship to Americans. Renounce your country, they say, join ours instead.

This is the first step toward the borderless future of Terra Ignota, the utopian sci-fi series masterminded by history professor Ada Palmer. In an author’s note to the first book, she says, “I wanted to add my voice to the Great Conversation, to reply to Diderot, Voltaire, Osamu Tezuka, and Alfred Bester, so people would read my books and think new things, and make new things from those thoughts, my little contribution to the path which flows from Gilgamesh and Homer to the stars.”

She does. Her books build upon the values those philosophers once espoused but don’t see the modern democratic nation-state as their logical end. Instead, she extrapolates their ideals into a future even freer than we have thus far conceived, and imminently possible. European countries have already opened their borders to each other. Now, skilled work visas, remote work visas, and golden visas, have steadily opened them to the world. Americans, for all our talent and money and contributions to the economy are desirable citizens to have.

Given the right breaking point, Americans might very well leave en masse.

And not just to Europe.

On the heels of the European announcement, the owners of Terra Ignota’s three transportation networks step forward to offer another kind of citizenship—one no longer bound by geography. They have long used their flying cars to facilitate international travel, evacuate companies from countries that would spell their economic collapse, and remove citizens from despotic nations, now they are large enough to support their users with deeds and healthcare—to become a state in their own right.

“For more than a generation we have not just been your travel agents but your banks, your lawyers, your hospitals, your schools, now let us be your nations,” they say. “[We] call on all Americans who do not support this war to renounce your citizenship and trust us—any one of us, you have your pick. Let us protect you and your families in this new, free world.”

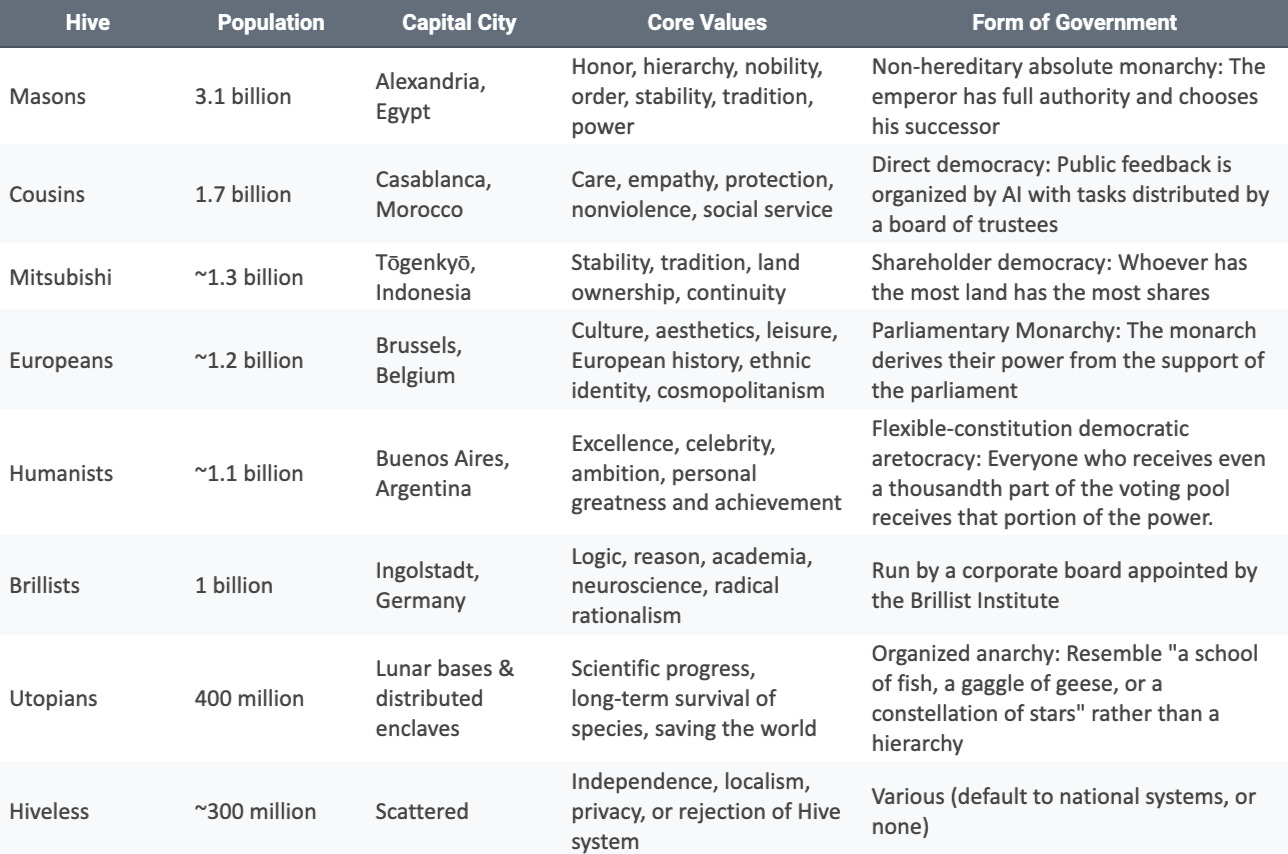

By the year 2454 when our story takes place, nation-states have dissolved and citizens join borderless “hives” instead—there are seven to choose from depending on one’s aptitude: The Masons, the Cousins, the Humanists, the Europeans, the Brillists, the Mitsubishi, and the Utopians. Let’s not forget the “hiveless,” a sort of anarchist faction that doesn’t adhere to any of them.

Only the Europeans start off as anything resembling a government, the rest are “network states” that evolved from other institutions. The Cousins were an online network for international travelers. The Humanists began as the Olympic Committee. The Brillists were an academic research institute—they still have a headmaster and board appointed by their institute. The Mitsubishi expanded out of their business model and, after merging with Greenpeace, formed a “shareholder democracy” where whoever owns the most land has the most power.

If our future nations begin as online platforms, universities, and businesses; those entities are already gaining autonomy and influence on the world stage. Metanational corporations employ and provide benefits for workers around the world. Global mobility organizations like Plumia might easily form a nation from their international networks. The Nature Conservancy owns vast tracks of land—5 million acres in the US, 100 million acres globally, plus tens of millions of protected ocean acrage—and could establish its own territory if needed. Humanitarian NGOs like Doctors Without Borders or the International Red Cross already have quasi-diplomatic status and could expand their services around the world.

Any one of these organizations, as well as many others, might just be waiting for the next World War to step up and offer an alternative. To proclaim: We’re a state now. Leave your terrible government behind and join ours instead!

Maybe we’re just waiting for the breaking point that will force that hand.

Maybe it’s approaching.

Technological innovations have made leaving even easier to do. Companies around the world went fully remote during the pandemic—might they do so again rather than risk collapse in a failing country? We may not have flying cars that can whisk us to another country in half an hour, but we have satellites that provide internet access anywhere, online banking that provide access to our money everywhere, and global health insurance policies that protect us around the world.

One thing we’re not considering in our perpetual fear of World War III: Maybe we won’t stand for it. One hundred thousand people left the US to evade the Vietnam draft—how much easier have technological advancements make it to leave today? Or to evade an unpopular war tomorrow? While it’s true that wealthy individuals can more easily emigrate, a rich economy like America shuffling about the world could drastically deflate the country’s power, and empower the countries they join.

What starts with America could create an easier wave of emigration around the world as others flee their bad governments too.

That’s exactly what happens in Terra Ignota.

In Palmer’s future, the Masons have become the most popular hive with 3.1 billion citizens. The group became a nation after a power grab by a firebrand leader sparks a resurgence of freemasonry ideals. The empire has a strongman dictator hailed “Caesar,” and is kept from becoming totalitarian only because its citizens could easily leave and join another hive if they aren’t happy with the strongman’s choices.

It’s an accurate assumption that most people would choose a dictatorship if they could. The Masons serve as a philosophical continuation of the Roman Empire and we’re already witnessing that resurgence. MAGA-like movements have spread internationally, idealizing Rome’s nostalgia for a past golden age, reviving imperial grandeur and national pride, and worshipping power and military might over democratic ideals. That movement will only gain steam as whatever America becomes merges with other strongman ideologies internationally and people clamor to join their movements, stomping and cheering for the authoritarian leaders they worship.

My favorite hive is the second most populous of the Terra Ignota world and a powerful counterpart to the Masons: The Cousins began as an online platform for women traveling abroad—a place where anyone could ask for travel recommendations, a safe place to stay, or help with their visas, and community members would offer up their homes, visa recommendations, and resources. Eventually, the platform is extended to friends of members and finally to "anyone willing to act like a distant ‘cousin’ and offer smiling airport pickup and a sofa for the night to a stranger in return for knowing that the stranger would reciprocate.”

Modern counterparts might include the platforms HomeExchange, CouchSurfing, WarmShowers, and Trustroots, where community members already provide free places to stay for international travelers. Similarly, Workaway and WWOOF provide international room and board in exchange for work. Timebank platforms allow volunteers to earn credits for helping one another and receive help from community members in return. Online LessWrong and Effective Altruist forums espouse ideals of being of service to one another, and apps like Buy Nothing have created networks of people exchanging goods without money.

Any of the above might become a future nation of Cousins.

Though the Masons might deride these Good Samaritans as too empathetic or “woke” for their sensibilities, the Cousins are also the world’s most essential hive, running its hospitals, orphanages, nursing homes, and prison programs. They provide disaster relief services and build playgrounds for communities. By the time of the first Terra Ignota book, the Cousins have nearly 2 billion members—and they’ve made technological improvements. Their online “Suggestion Box” is now fitted with an AI that processes a hundred million notes a week, groups the overlap, and sends those needs on to the volunteer network to get done.

“‘This town needs a new school,’ ‘This drug needs a sixty-million-dollar research grant,’ ‘This intersection would be a great place for a mural,’” our narrator illustrates. “They get it done, this vast, cooperative ‘family.’ It works.”

I would be a Cousin if I could choose my nation this way, though I am also tempted by the Utopians. The smallest hive by population, they are also the world’s richest for their patents. Once an eclectic group of futurists, the Utopians of Terra Ignota are an “organized constellation” of dreamers working to improve the world of tomorrow. Their capital city sits on the moon and they are working to establish a second base on Mars. It is their technology that powers the trackers that monitor our health and the anti-aging medicines we all take—65 is now the midpoint of our lives.

“Utopia does not give up on dreams,” our narrator says. “When a Utopian dies, of anything, the cause is marked and not forgotten until solved. A fall? They rebuild the site to make it safe. A criminal? They do not rest until he is rendered harmless. An illness? It is researched until cured, regardless of the time, the cost, over generations if need be. A car crash? They create their separate system, slower, less efficient, costing hours, but which has never cost a single life. Even for suicide they track the cause, and so, patiently, blade by blade, disarm Death.”

Here I can’t help but think of Balaji’s network states co-mingled with Elon’s quest for Mars and Altos and Calico longevity institutes. We already have a loose collection of wealthy futurists working to disrupt the nation state, reach for the stars, and disarm Death. We see their analogues funding new cities like Prospera, aiming for Mars, and popularizing the motto “Don’t die.” If the modern tech set are already approaching Utopian-like nationhood, they are just as controversial today as they are in Terra Ignota’s future: Their ideals seen as caring too much about the world of tomorrow and not enough of the worries of today.

Utopians, however, are an important part of the Terra Ignota world, as they are in ours. We need visionaries. We need a small faction of dreamers dreaming about tomorrow even as the rest of the world focuses on today. That’s why killing a Utopian comes with the gravest of consequences: They are no longer allowed to read or watch fiction. “You destroyed a potential other world,” our narrator explains, “so you get banished to this one.”

If Terra Ignota’s hives have caused the dissolution of the nation state, they also lead to our salvation. By the time of the first book, the world has been at peace for more than 300 years. There are no longer weapons of mass destruction, no nations to war against. Ethnic groups have spread across the world and members of the same household might belong to different nations—who could we possibly war against?

Before you ask, Palmer does away with religion too. America’s so-called “Church War” made everyone realize it was just too dangerous. In her future, religion is practiced privately and is forbidden from being practiced publicly. Instead, each member is assigned a “sensayer,” a professional trained in all the world religions and philosophies who can help their mentees understand the world without venturing an understanding of their own. As one child describes it: A sensayer is somebody who loves the universe so much they spend their whole life talking about all the different ways that it could be.

Here Palmer wrestles with an important dynamic: Almost anything that turns out utopian can also be dystopian in the wrong hands and religion is no different. As a religious scholar myself, I can so easily see the ways religion can be used for personal good, even as it is used for public harm. Palmer tries to solve that problem by allowing the former and outlawing the latter. It’s an interesting solution to a pressing world problem, and I won’t fault it for its impossibility. If I were to venture my own religious ideal, however, we would get there by evolution, not regulation.

Religion, in a lot of ways, has already become personalized. Though we might celebrate Christmas or practice meditation, we have adapted our faiths, keeping the rituals and labels we choose without needing to adhere to every belief or practice. Every Christian does not practice the same Christianity. Every Buddhist does not practice the same Buddhism. Our religions have become more flexible this way, and perhaps we will continue to evolve in that direction. Maybe we will even arrive at Palmer’s ideal—8 billion people on the planet means 8 billion religions—in many ways I think we’re already there.

If we still have the dangerous sort—the religious zeal that has resurged in the US and Middle East—might that also be curtailed by a more globalized and interconnected world? After all, emigrants tend to be less religiously zealous than those who remain in their home countries, their children even less so. Maybe it’s not religion that’s the problem, but ethnic nationalism that concentrates in place. Easier immigration could deflate the zealotry that still causes so much harm, while keeping the personal practice that can still cause such personal good.

That doesn’t mean we will arrive at a future without power dynamics. In Terra Ignota, the “Alliance” is now our world government. Gathered in a re-creation of ancient Rome called Romanova, each hive is represented by senators proportional to the share of the world population they have—as a result, population shifts mean power shifts. In the first book, these are minor—the Mitsubishi lose a senator as citizenship declines, the Masons gain two as theirs grows—but the Masons are fast approaching 33% of the world population, and if they do it’ll only be another 20 years before they have a monopoly. When it’s discovered that the Cousins’ AI system has been tampered with, they risk dissolution as members flee to other hives, upsetting the power balance and leaving good Samaritanism behind.

It is this disrupted balance that sets the stage for the central conflict in the series as we see a populace who has long forgotten war wondering if they should resurrect it, and who they should fight it against. Like many utopian novels, however, its plot is its weak point: Magical characters transform into different ones along the way, an odd god from another world is somehow living among them, and long stretches of each book concern events entirely irrelevant to the story. At the same time, Palmer’s incredible worldbuilding and powerful use of narrative make them all worthwhile. In many places her books reminded me of the Battle of Waterloo in Les Miserables—completely irrelevant to the story, but beautiful all the same for the author’s philosophical worldview imparted within. It’s worth the unabridged version, both there and here.

Palmer weaves her rich understanding of the past into the future, filling the pages with philosophers and inventing new ones who will carry their torch. Our narrator is the ideologue Mycroft Canner who insists on speaking like an 1700s philosophe as he veers into lengthy asides about Diderot or Rousseau, Bacon or de Sade. He credits Epicurus with the invention of the bash’—the co-living houses that have replaced the nuclear family—and the Utopia writer himself for inventing the servicer program he, as the world’s most notorious criminal, now participates in. Sir Thomas More’s fictional Persian judicial system is resurrected for the Terra Ignota world, with criminals sentenced to lifelong community service rather than prison. They have no ability to own anything or earn any income except the food they are given for their work. As our narrator recounts: “They served the community in ambitionless, lifelong peace.”

We don’t know how Terra Ignota’s borderless nations fund these programs in practice—the closest we get is during a re-enactment of “Renunciation Day”—the celebrated day when Europe and the transportation networks first offered an alternative nation to Americans. After they speak, a representative steps up to the dais to explain how these new nations will work. “No one remembers her speech, the technicalities of how to apply to join these new nongeographic nations, and how they will handle deeds and taxes, legal suits and health care,” our narrator says. “She is like the big sister packing our backpacks for the camping trip, who tries to make us pay attention as she goes through the items, but we ignore her, entranced already by the wild’s call.”

We certainly leave Palmer’s series entranced by the wild. If we don’t fully know how we will achieve the borderless future of Terra Ignota, we at least crave the many possibilities she makes available to us. Her future is the Enlightenment continued—it’s one we are actively building now. As our institutions crumble and crack with age, as technology renders them superfluous, we are reaching for whatever future will replace it. Palmer’s version is highly possible, and not too far off. Her future begins in 2073 when the first flying car circles the globe in four hours—is it so difficult to imagine how different our world could be then? Much less 500 years from now?

The utopian thinkers of the past once imagined a future that is in a lot of ways here. Francis Bacon never lived to see the scientific method, Voltaire never lived to see the separation of church and state. HG Wells never lived to see the United Nations. But we created their visions all the same—over decades, over centuries—inching our way toward their utopic visions of the world like a river carving a canyon over millennia. Palmer believes we are part of that process now and that is the legacy left to us, the modern utopians—or should I say Elysians—who dare to keep dreaming of what’s next without knowing if we’ll ever reach it.

Terra Ignota is Palmer’s modern entry into the utopian annals, and one of my favorites of the tradition. It reminds us that our future is not decided or limited by our present, but is still endless to those willing to imagine it.

Thanks for reading and dreaming with me, and a special thank you to

, , and for editing an early draft. This one is much better because of your feedback.P.S. I study utopian novels and write reviews of them—Terra Ignota is only the most recent of the series. Here are a few others I’ve written on climate utopias, feminist utopias, and socialist utopias: